Fires in Edinburgh

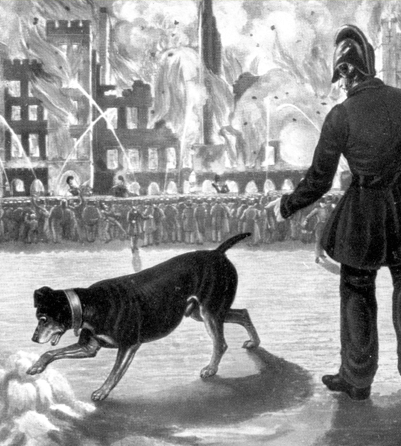

In 1824 the city suffered a series of fires, culminating in what became known as the Great Fire of Edinburgh.

The fire started on the 15th November and lasted for four days, making hundreds of people homeless and caused 13 fatalities including the lives of two firemen.

These fires were the catalyst for the creation of the world’s first municipal fire brigade, called the Edinburgh Fire Engine Establishment (EFEE).

View slides

Order out of chaos

Edinburgh was a growing city, but many of the poorer inhabitants lived in derelict buildings in the Old Town, which suffered from a series of fires in 1824. Existing insurance company fire fighting services struggled to tackle these fires.

“There was no want of zeal; but a want of concert was often observed; and there was no such preparation, or previous organisation of means, as would necessarily have existed, had the engines, men and assistance to be taken on such occasions, been under the command or control of a person paid for the purpose.”

The above extract, taken from The Scotsman, highlights the frustrations of one observer witnessing the efforts to control a serious fire in Edinburgh Old Town in July 1824. It went on to state: “decency, the general interests, humanity, call loudly for new and efficient arrangements.”

The issue of disorganisation was neither unique, nor new and the above would have been a fairly accurate reflection of what was also happening in other parts of the UK.

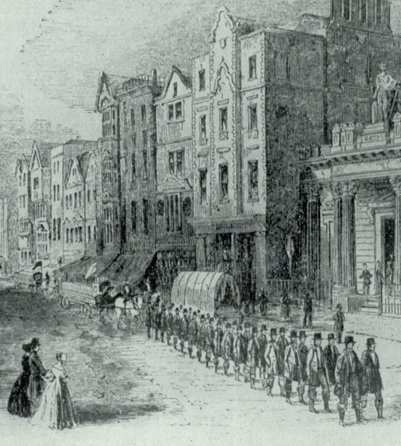

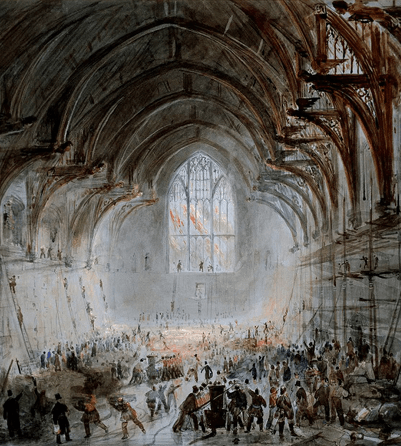

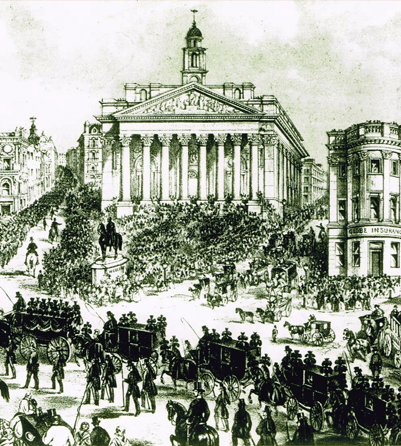

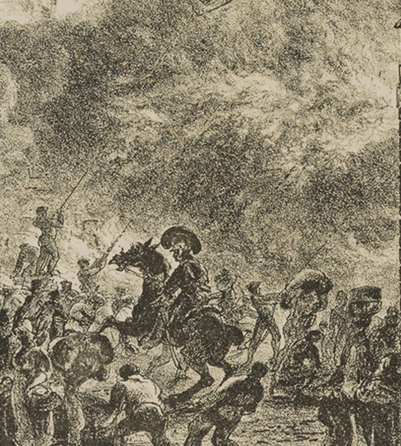

Scene from the Great Fire of Edinburgh

First sighting of Braidwood?

It is possible James Braidwood made his presence felt by offering assistance at these fires, even before he was made Master of Fire Engines. A report in the Scotsman dated 28th April 1824 might throw some light on the matter. Reporting on the serious fire at the Brass Foundry it states:

“The fire raged with great violence, particularly at the back part of the premises, so that before eight o’clock not only the foundry but the whole range of printing premises were enveloped in one dreadful and destructive flame, exhibiting a scene at once fearful and awfully grand! Upon the arrival of engines from Leith and a better supply of water having been procured by the judicious arrangement of a private individual whom we perceived as being very active during the whole time, a decided impression was made in checking the progress of the flames. The water had been carried in buckets during the whole previous part of the morning from the High Street, when the above individual solicited three spare engine pipes got them screwed to the water pipe in the high street, which conveyed the water without waste to the top of the acclivity in Niddry Street, and by adding a few more, at last got the water conveyed to the very sides of the engines.”

Could the private individual in question have been James Braidwood? Brian Henham, author of “True Hero” is certain it was. He says “Bearing in mind the almost total lack of firefighting expertise available at that time, perhaps it would be more appropriate to ask whether in fact, it could have possibly been anyone else.”

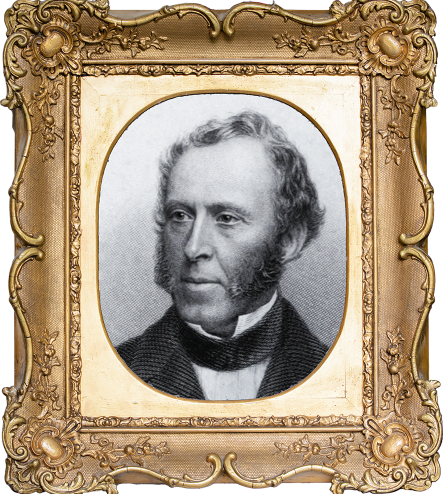

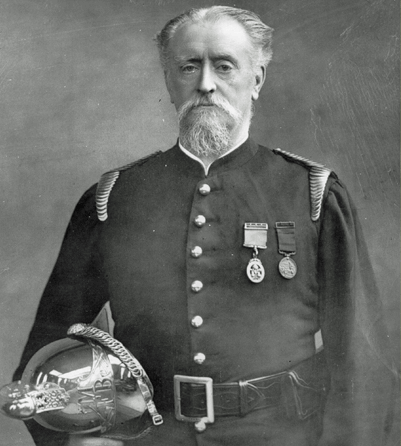

Brian Henham, author and fire historian

Formation of the EFEE

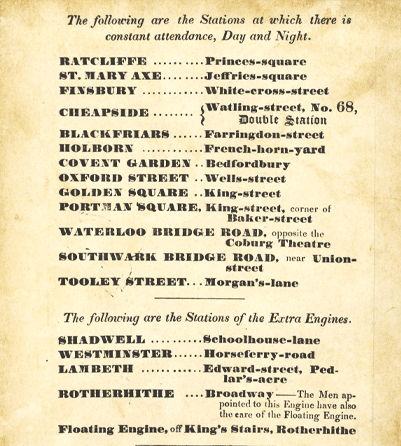

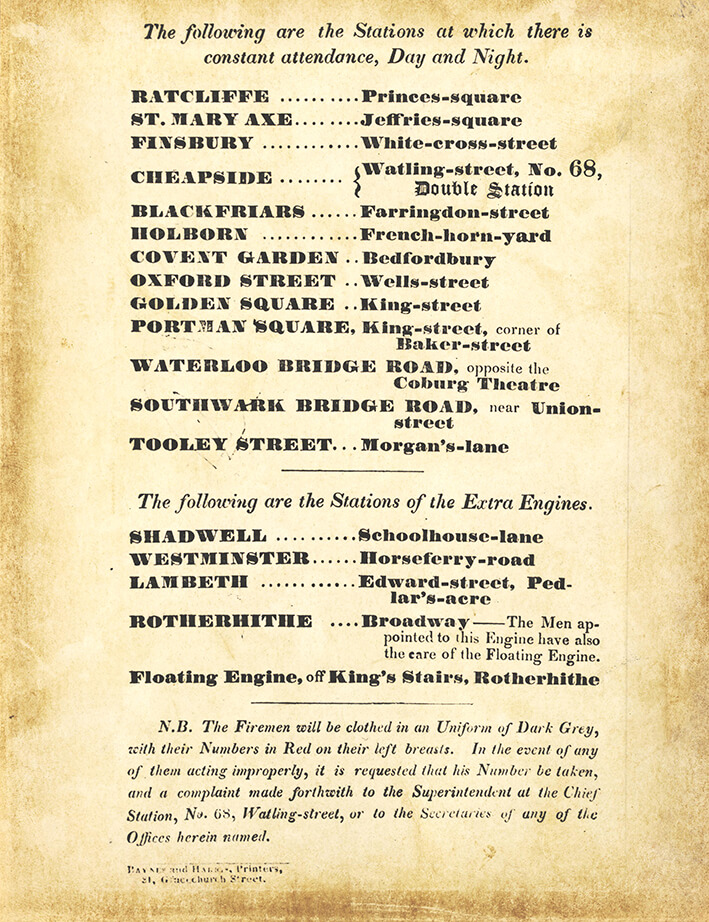

A Fire Engine Committee was set up to deal with the crisis. They concluded that Edinburgh was dependent upon a mere three fire insurance engines, with firemen of the various offices “often wrangling and quarrelling in place of joining their efforts as they ought to do.” They also complained about the “great want of fire plugs”.

The committee recommended:

- A sufficient number of engines be provided

- Adequate fire plugs to be provided

- A superintendent be appointed to direct the engines

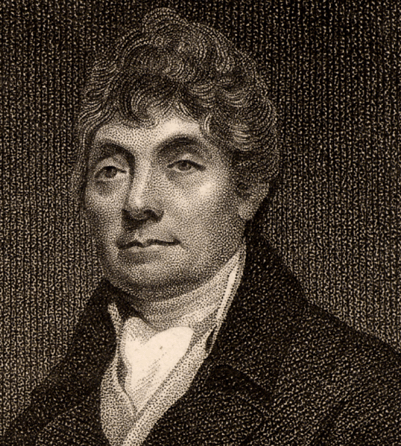

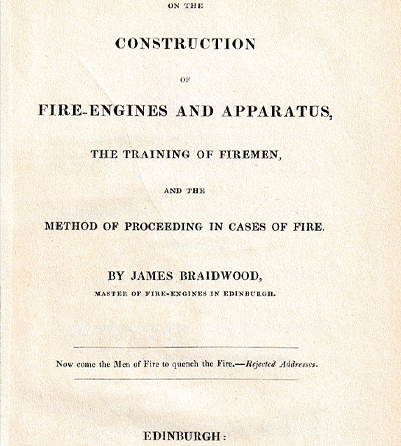

The result was the establishment of the world’s first organised municipal fire brigade. When they looked for someone to lead it, James Braidwood seemed the natural choice, with his understanding of buildings and firefighting experience. At just 24 years old he was appointed Master of Fire Engines.

James Braidwood kept meticulous records whilst leading the EFEE. Image courtesy Brian Henham.

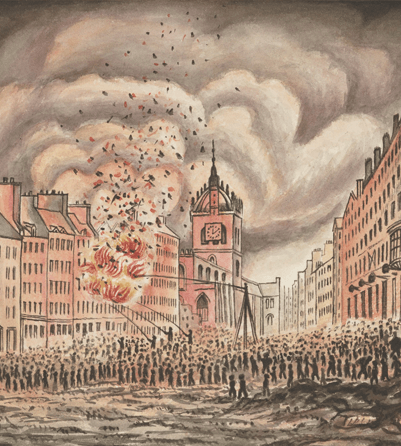

Great Fire of Edinburgh

Only three weeks after Braidwood’s appointment, a major fire broke out in the city. It was one of the most destructive fires in the history of Edinburgh and lasted for five days. Due to the narrowness of the alleyways the fire spread quickly and without enough fire cocks, the firemen found it difficult to locate a water supply.

An estimated 400 homes were destroyed with 400-500 families left homeless. Thirteen people died including two firemen.

Braidwood was criticised for how the episode was handled, but it was accepted that he had not had enough time to reorganise or train his brigade to make enough impact.

Ultimate authority was also in the hands of several men rather than a single person trained in firefighting and as a result, conflicting and confusing advice was given to the firemen, who were trying desperately to put out the fire.

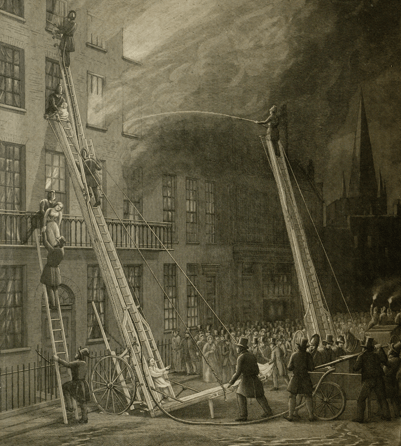

Firefighters tackling the blaze.

Master of Fire Engines

The EFEE made Braidwood the sole person of authority to avoid confusion at the scene of the fire and he made significant improvements to firefighting in Edinburgh.

He split the town into four districts, each with its own engine station and specific colour. These stations had a company of men under the command of a captain or Head Engineman.

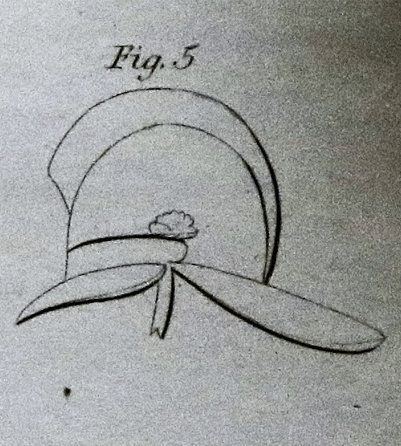

Firemen worked part-time and were usually aged between 18-25. They tended to be recruited from the building trade. Each wore a blue tunic, white canvas trousers and leather helmets painted in the colour of the company to which they belonged.

By the end of 1824, the total force consisted of 80 men, who Braidwood committed to a training regime which generally took place at 4am, initially once a week and later once a month. He set up small gyms to encourage fitness.

Among all the new ideas Braidwood introduced, the most important was to get water direct to the seat of the fire. In most cases this necessitated his men going into burning buildings.

He introduced new fire fighting measures including enlisting the help of the police in crowd control and closing external doors and windows in unoccupied buildings, in time for the engine’s arrival. He also introduced the idea of a hose being taken up to the fire floor, by using rope to pull it up outside the building.

Return to start

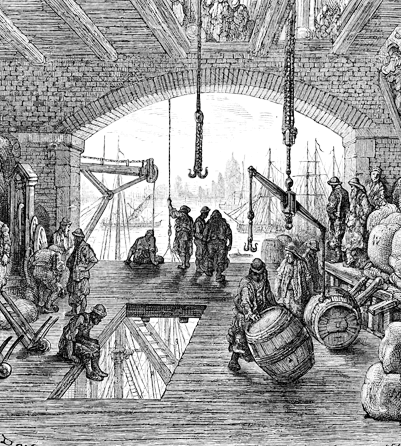

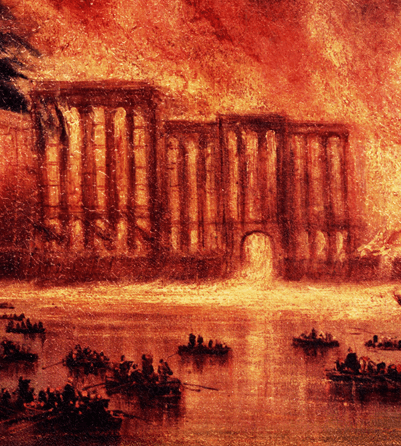

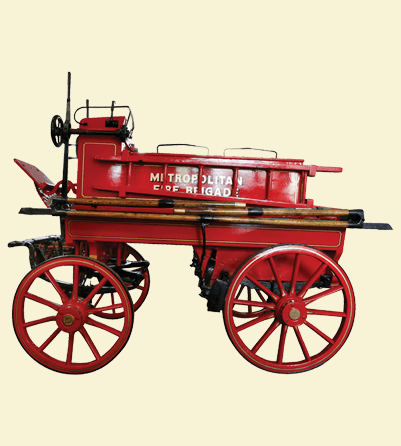

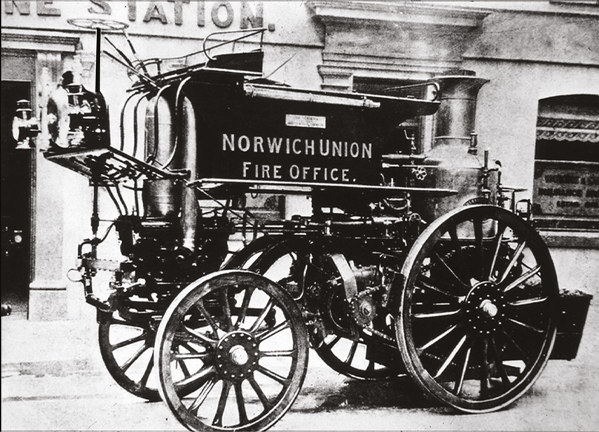

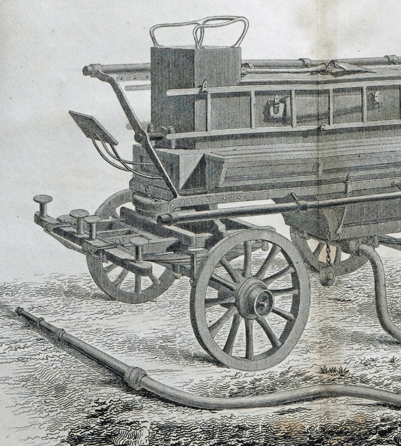

A manual fire engine. Braidwood trained the firemen to operate these vehicles which had no fitted brakes, which was dangerous on the steep hills of Edinburgh.