Coffee Houses

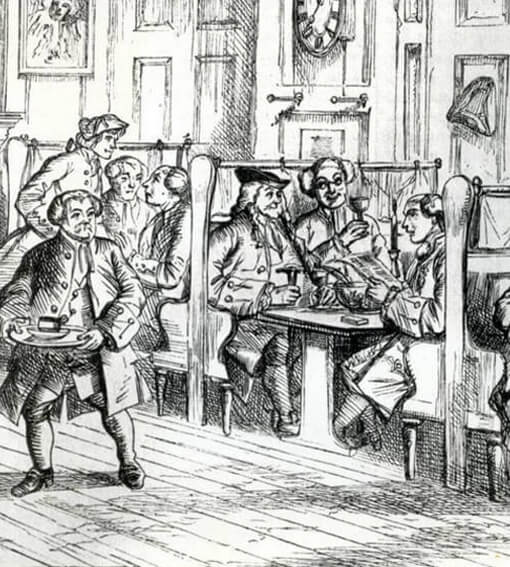

English coffee houses of the 17th and 18th centuries were important centres for men to meet for conversation, news, debate and to conduct business.

Few merchant offices existed, and many companies and associations were founded in coffee houses at the time.

View slides

Tour Guide

The arrival of the coffee houses in London.

With Pete Zymanczyk

What were coffee houses like?

With Pete Zymanczyk

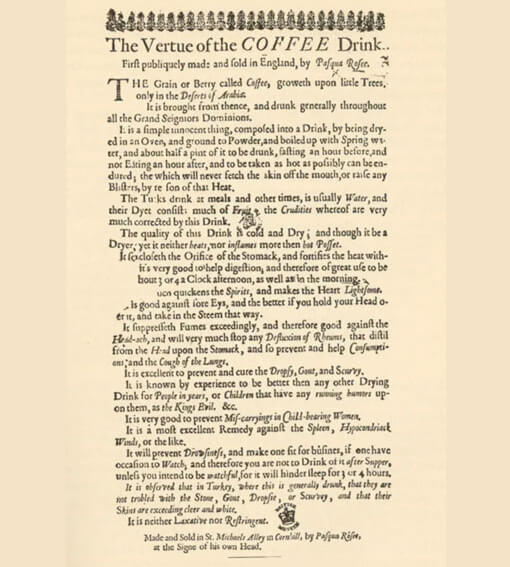

Pasqua Rosée

According to the diarist Samuel Pepys, England’s first coffee house was established in Oxford, in 1650 by a Jewish gentleman named Jacob.

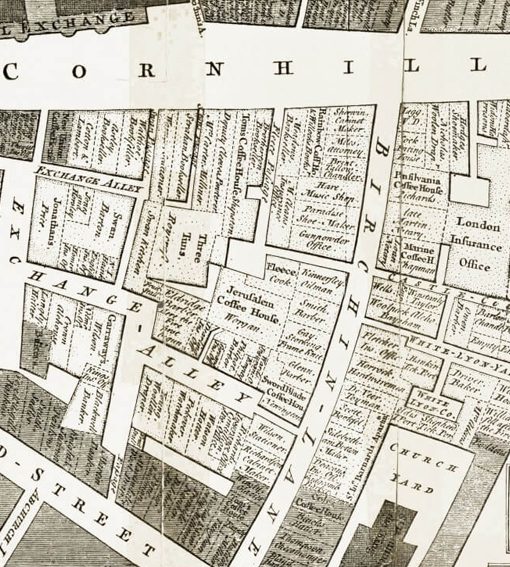

The first coffee house to open in the City of London was that of Pasqua Rosée in St. Michael’s Alley, Cornhill in 1652. Rosée was the Armenian-born servant of a merchant named Daniel Edwards. Edwards took up coffee drinking while based in Turkey and part of Rosée’s duties was to continue to make Edwards’ coffee when he returned to his London home.

Rosée first set up a coffee-serving stall in St Michael’s churchyard, near the Royal Exchange, to entertain Edward’s guests who were curious about this drink. Such was his success, that within a year or two he’d earned enough to open the first coffee house.

By the end of the 17th century it is estimated that there were nearly 3,000 coffee houses in England.

Edward Lloyd's

No history of coffee shops and insurance would be complete without mention of Edward Lloyd’s coffee house, which he first opened on Tower Street. His coffee house was first mentioned in an 1688 edition of the London Gazette.

The coffee house was a popular meeting point for sailors, shipowners and merchants (very few of whom had their own offices). It became a business hub for those involved with marine insurance and trade.

This was the birthplace of the Lloyd’s, which remains famous today as the world’s leading insurance and re-insurance market.

Edward Lloyd employed runners to report from London’s docks with fresh news of ship arrivals and departures. He built up a network in ports across Britain, which would send him information on comings and goings, storms, piracy or sightings of other ships on voyages. He provided all the information merchants, insurers and investors would need to know.

Within his coffee house, Lloyd had a pulpit from which news was regularly read and reserved an area for ship’s captains and retired captains. Presumably this may have given Lloyd’s coffee house kudos, showing the direct links to the maritime trade, but perhaps this was also part of the “information hub”, with potential investors being able to consult with the actual people who had sailed the trade routes and had local knowledge.

Lloyd also held ‘candle lit’ auctions for ships, the tradition for this was that when the candle had ‘burned out’ the auction bidding was complete.

In 1691, he moved to Lombard Street, closer to the centre of business. Insurance underwriters and brokers found his services so useful that they rented boxes (booths or tables) in his coffee shop for meetings with their clients. Such ‘boxes’ still exist in Lloyd’s of today.

Lloyd’s list

As early as 1692, Edward Lloyd collated all his shipping information and intelligence, and launched Lloyd’s News. Unfortunately, the newsletter did not last long, but was revived in 1734 as Lloyd’s List. Although Edward Lloyd died in 1713, his coffee shop was taken on by a series of owners and the name was kept. It was Thomas Jemson that revived the newsletter under the name of Lloyd’s List, which continues today.

In 1769 a group called ‘New Lloyd’s Coffee House’ broke off from the Lombard Street coffee house, to disassociate their trade from the disreputable practices of gambling and stock-jobbing. After residing in Pope’s Head Alley until 1794 they moved to the Royal Exchange, where they remained until 1928. Membership of ‘New Lloyd’s Coffee House’ was by subscription from 1771.

London Coffee Houses

Hundreds of coffee houses opened across London, attracting a diverse range of customers.

The coffee houses developed into focal points for customers with specific interests or knowledge.

Rainbow Coffee House

The Rainbow Coffee House, located in Fleet Street was opened by James Farr (a former barber) in 1657. Although not popular with the neighbours due to the smell of burning coffee and chimney fires, the Rainbow Coffee House, was a great success and survived the Great Fire of London. In 1666, it issued a promotional coin decorated with a rainbow and smoke cloud.

Read more...People met there to exchange information and do business, it also served as a meeting house for Freemasons, French Huguenot refugees, writers, theologists and many others.

Nicholas Barbon's Fire-Office promoted their insurance rates in pamphlets and advertised that they had an agent based at the Rainbow Coffee House.

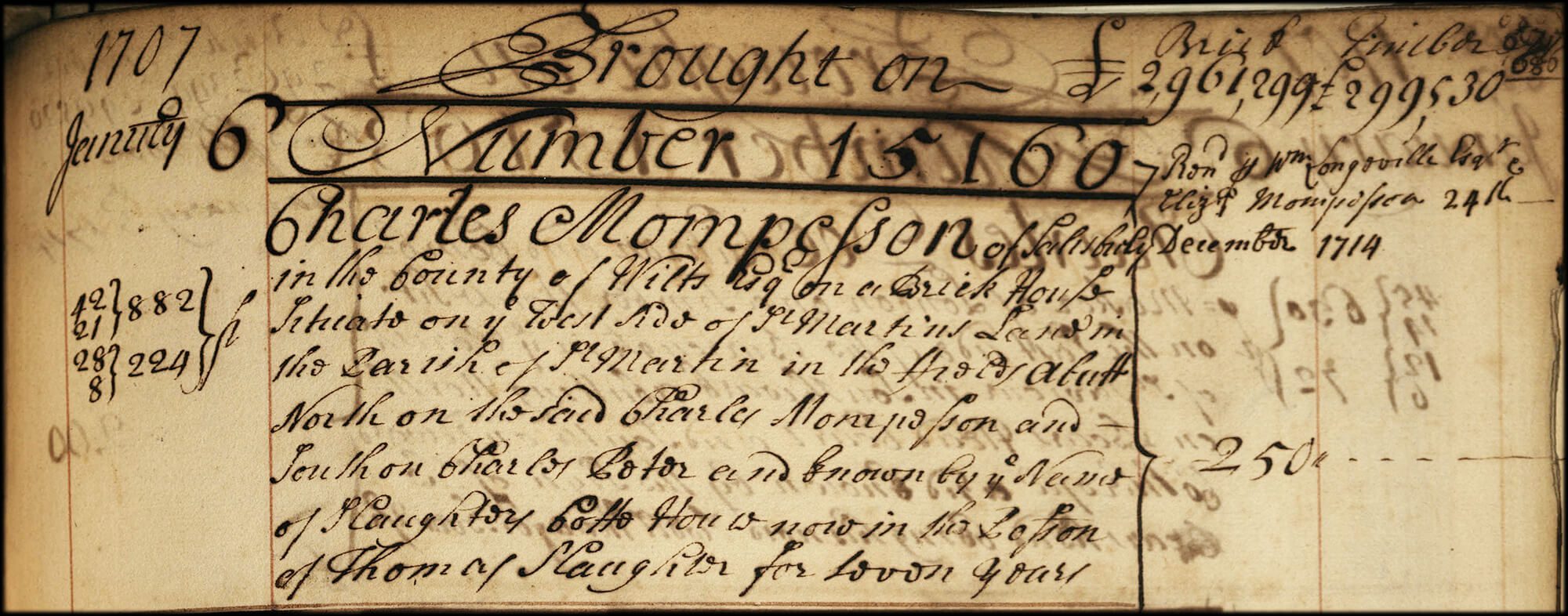

Tom Slaughter's coffee house

Tom's opened in 1692. Many years later it became known as Old Slaughter's to distinguish it from New Slaughter's coffee house.

The coffee house became a centre for games including draughts, whist and chess, holding the only known chess club in London.

Notable patrons included artists Hogarth and Gainsborough, novelists Daniel Defoe (also an insurance underwriter) and Henry Fielding...

Read more...... Abraham de Moivre was a famous mathematician and a friend of Isaac Newton, who was often at Slaughter's selling advice on risk, or the 'chance of loss'.

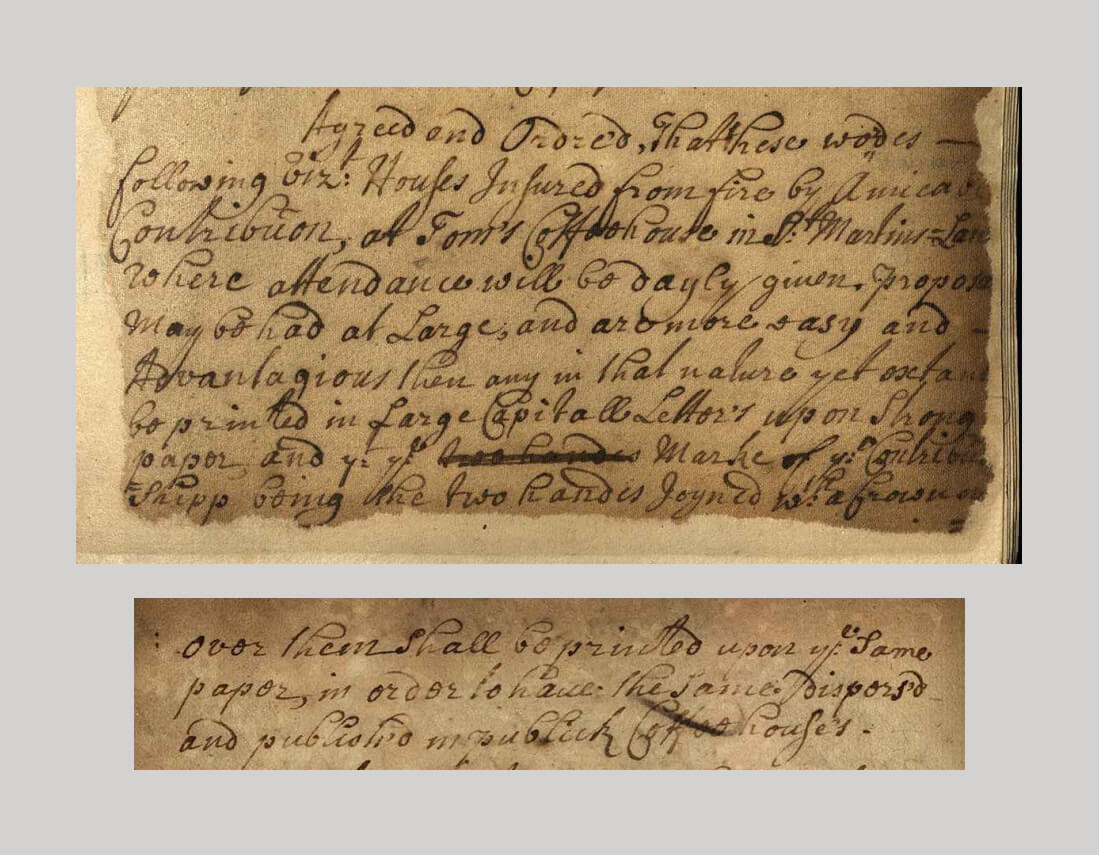

It was here that the 'Contributors for Insuring Houses, Chambers or Rooms from Loss by Fire, by Amicable Contribution' was formed.

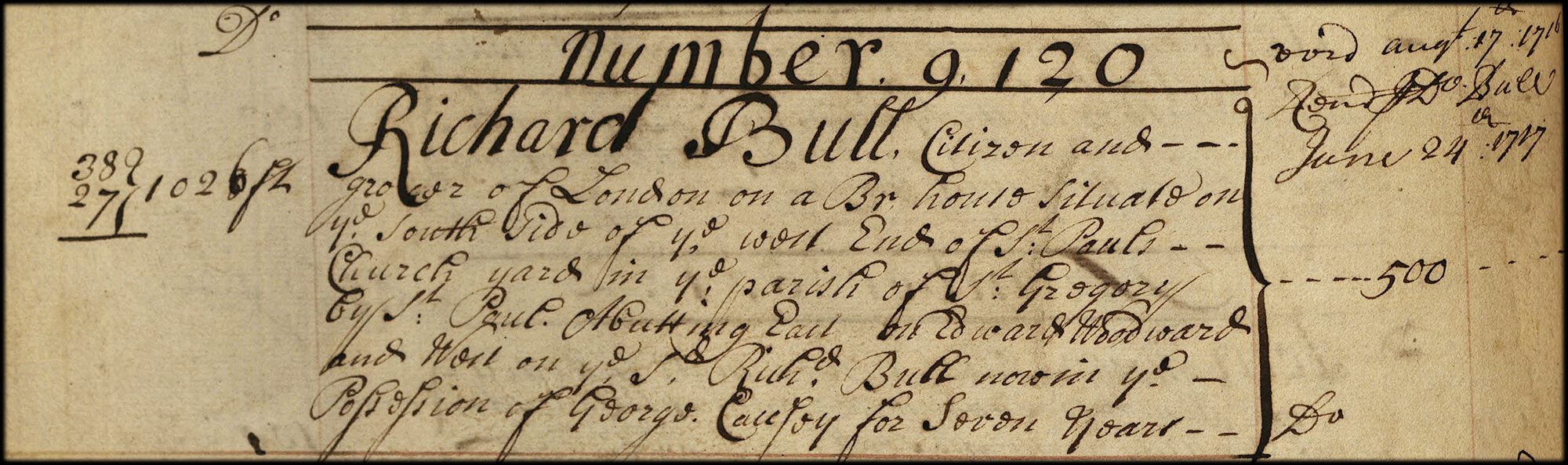

Paul's Coffee House

In 1710 Charles Povey organised the sale of his Exchange House Fire Office (which used the Sun symbol as its fire mark) to the Company of London Insurers.

Povey arranged that ‘this day the Company did agree with George Causey (called afterwards Coffee-man) for one room in his house called the Paul's Coffee House, for one year, at 15/. per ann., with the use of the forward Room for the General Meetings upon due notice, with a closet for Coals, his Servant to clean ye room and light the fire.’

Read more...Paul’s Coffee House was said to adjoin to Dean's Court at the West End of St. Paul's. On the 14th April, a sign was ordered and ‘that 16s, be paid to ye Carver for making ye Sun’.

Coffee Recipe

18th century coffee drinking was popular for keeping the mind and body alert, but contemporaries weren’t particularly enamoured by its taste.

Reports from the time describe it as tasting of “mud”, like “old crusts and leather” as “syrup of soot” and having an “essence of boiled shoes”.

If that sounds appealing, why not try and recreate it for yourself, by following this 18th century recipe (read more):

Step one:

Source some green coffee beans.

Step two:

Roast the green beans in a frying pan or skillet over a fire. Once the fire gets going you need to stir your beans until you start to hear them make a “cracking” sound, a bit like popcorn. Keep stirring them – it only takes a couple of minutes so don’t walk away!

Step three:

Grind your coffee beans into a coarse powder with a pestle and mortar. It is estimated that a 17th century cup of coffee was made with 30 to 50 grams of coffee per cup.

Step four:

Boil your coffee powder in water for about 15 minutes. Some coffee houses would boil it for longer, up to an hour.

Step five:

Pour your coffee into a shallow bowl or dish and enjoy…

Activity:

If you try making your own 17th century coffee, post a photo on our social media and let us know how you get on!

Coffee jug with 1700’s silver hallmark.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

Insurance business

Learn about the coffee houses as a centre for ideas and business.

With Peter Zymanczyk and Robin Pearson

Return to start

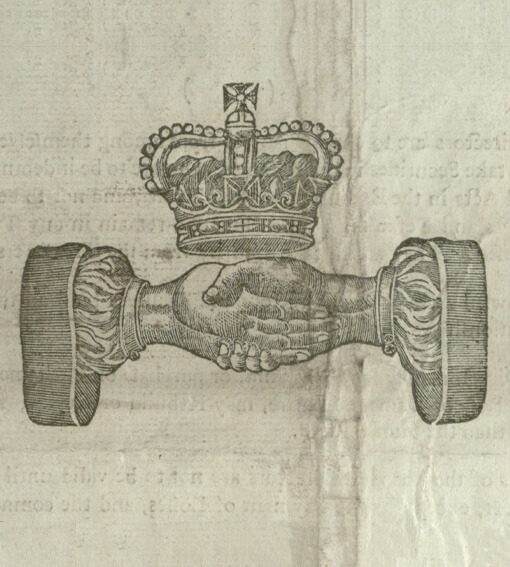

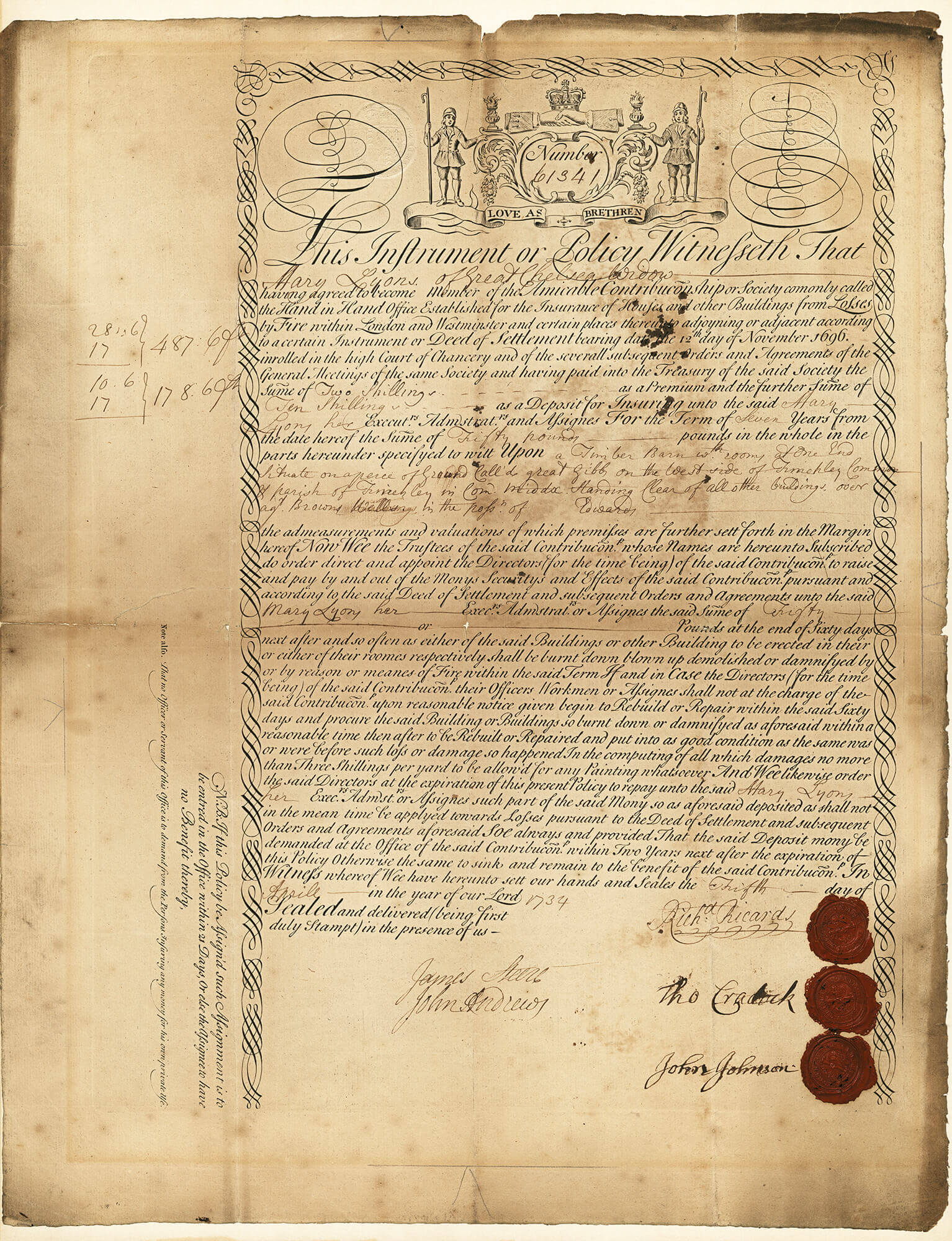

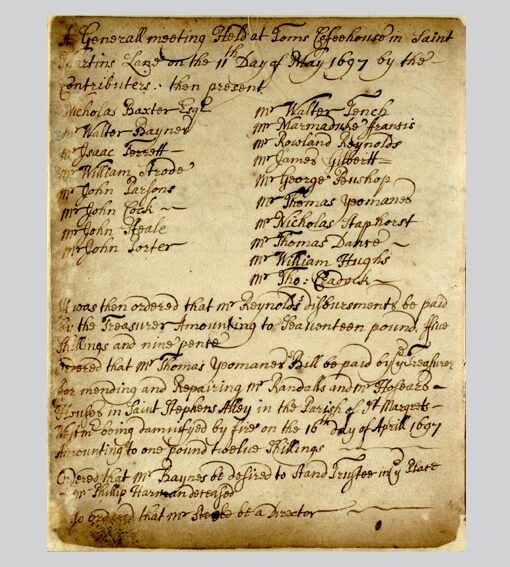

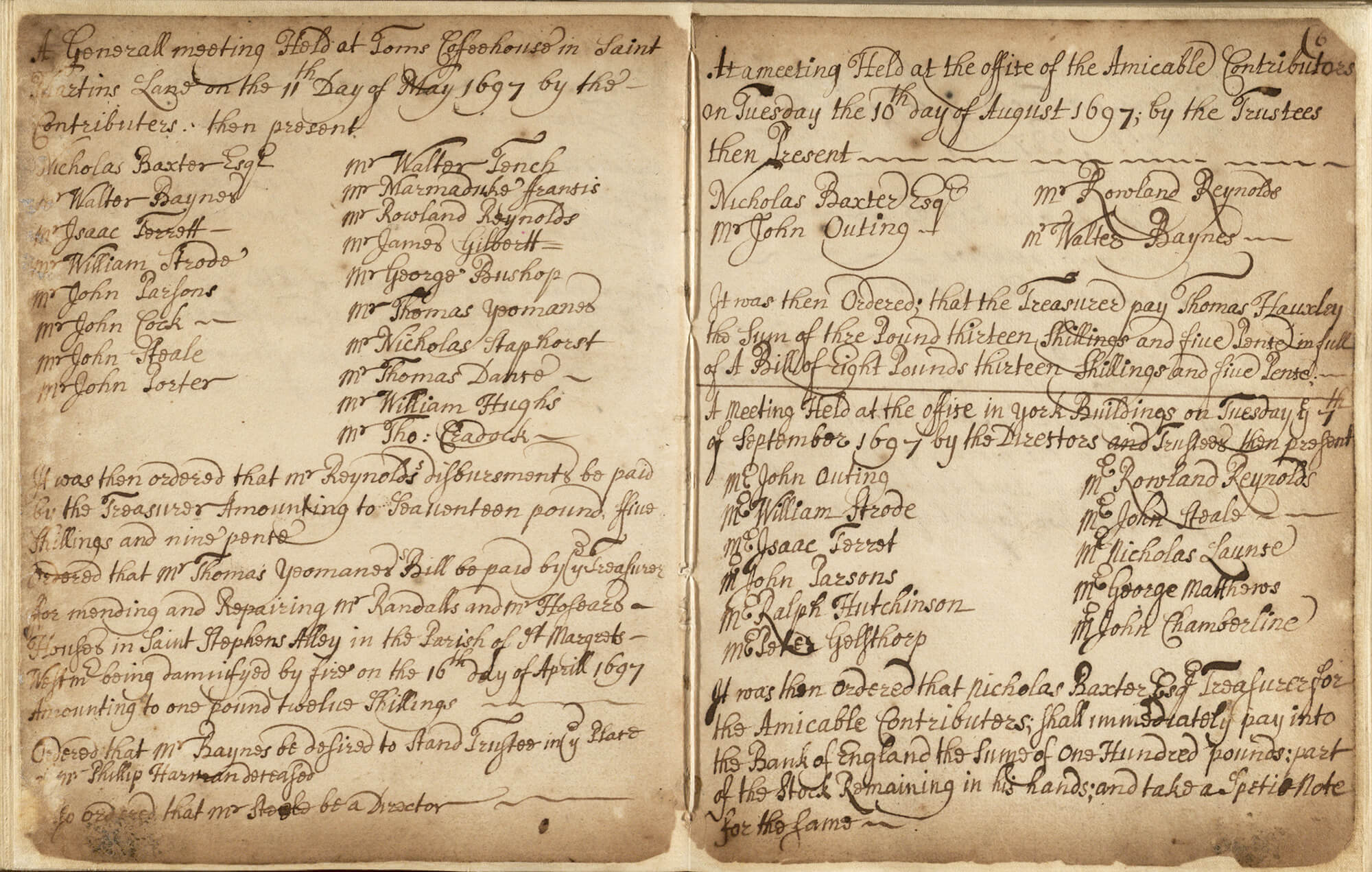

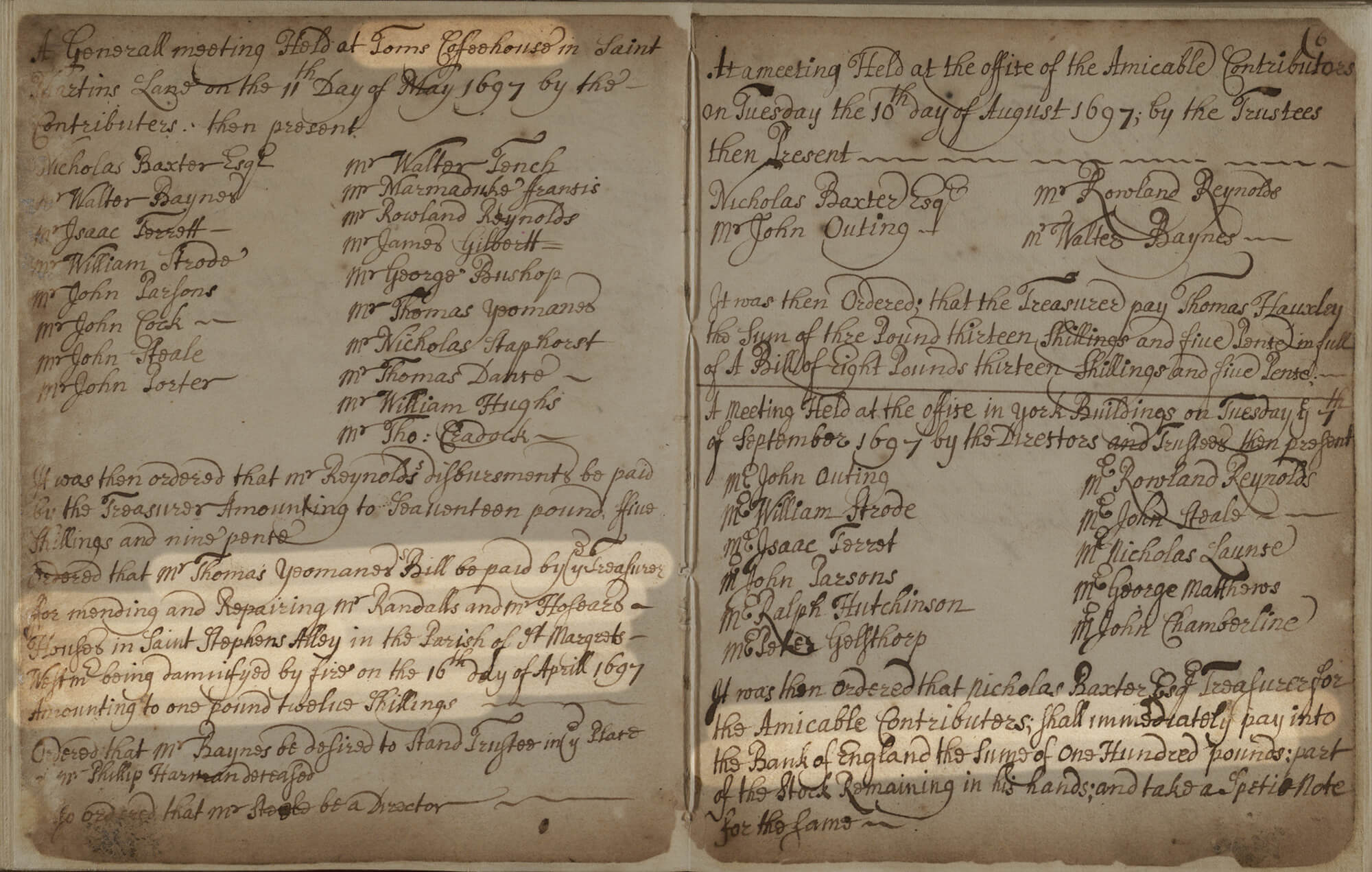

Contributors for Insuring Houses, Chambers or Rooms from Loss by Fire, by Amicable Contribution

This snappily titled company, later known as the 'Hand in Hand' (after its fire mark design) was formed in Tom’s Coffee House on the 12th November 1696

View slides

Fire Historian

Introducing the Hand in Hand.

With Brian Henham

Starting up

The Hand in Hand was set up with the singular purpose of providing fire insurance for buildings in London.

It was set up on a Mutual (or co-operative) basis for the sole benefit of those who insured with it. Dividends would be paid on profits but contributions from members would be sought every time there was a loss.

It changed its constitution very little over the years, from that originally drawn up in 1696. Yet, it was a significant pioneer of British fire insurance and was instrumental in developing early fire fighting and fire extinguishing techniques.

In February 1698, it was agreed that their area of business should be restricted to an area encompassing the Cities of London and Westminster and the Borough of Southwark. This restriction on the area was a sensible one. There was enough business to be had, travel was difficult and it could be very dangerous to venture further afield.

At the end of the 17th century, 600 houses were insured by the office.

Development

Until 1710, the Fire Office and the Friendly Society provided the only competition and the number of properties insured by the office approached 20,000.

1714 saw the formation of the Union Fire Office, and a number of their Directors were also Directors of the Hand in Hand, so unsurprisingly there was a great deal of co-operation between the two offices. The Union insured contents only and agreed to continue to do so, as long as the Hand in Hand only insured buildings. This agreement lasted until 1805.

In 1717 some of the directors and policy holders of the Hand in Hand were unhappy that the Hand in Hand moved their offices from the City of Westminster to the City of London. As a consequence, these directors split from the Hand in Hand and formed their own company as a competitor, called The Westminster.

By 1715 there were over 29,000 properties insured by the Hand in Hand fire office, at a total value in excess of £6 million.

Famous clientele

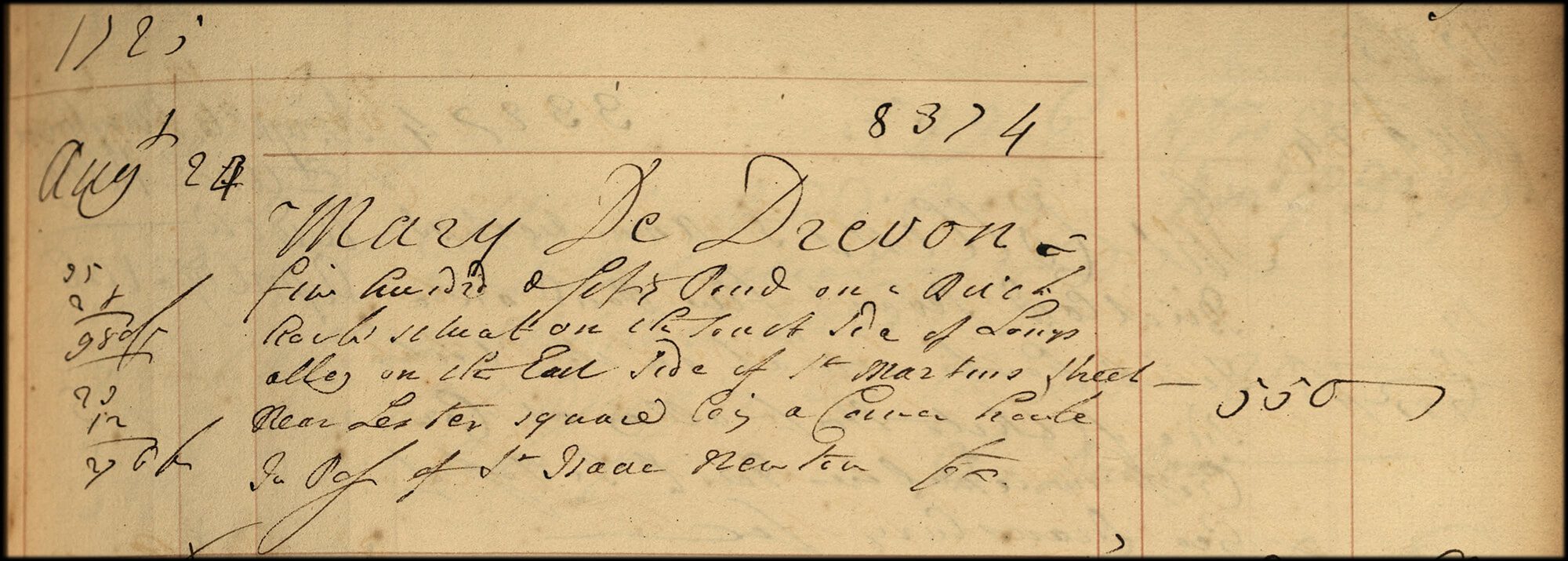

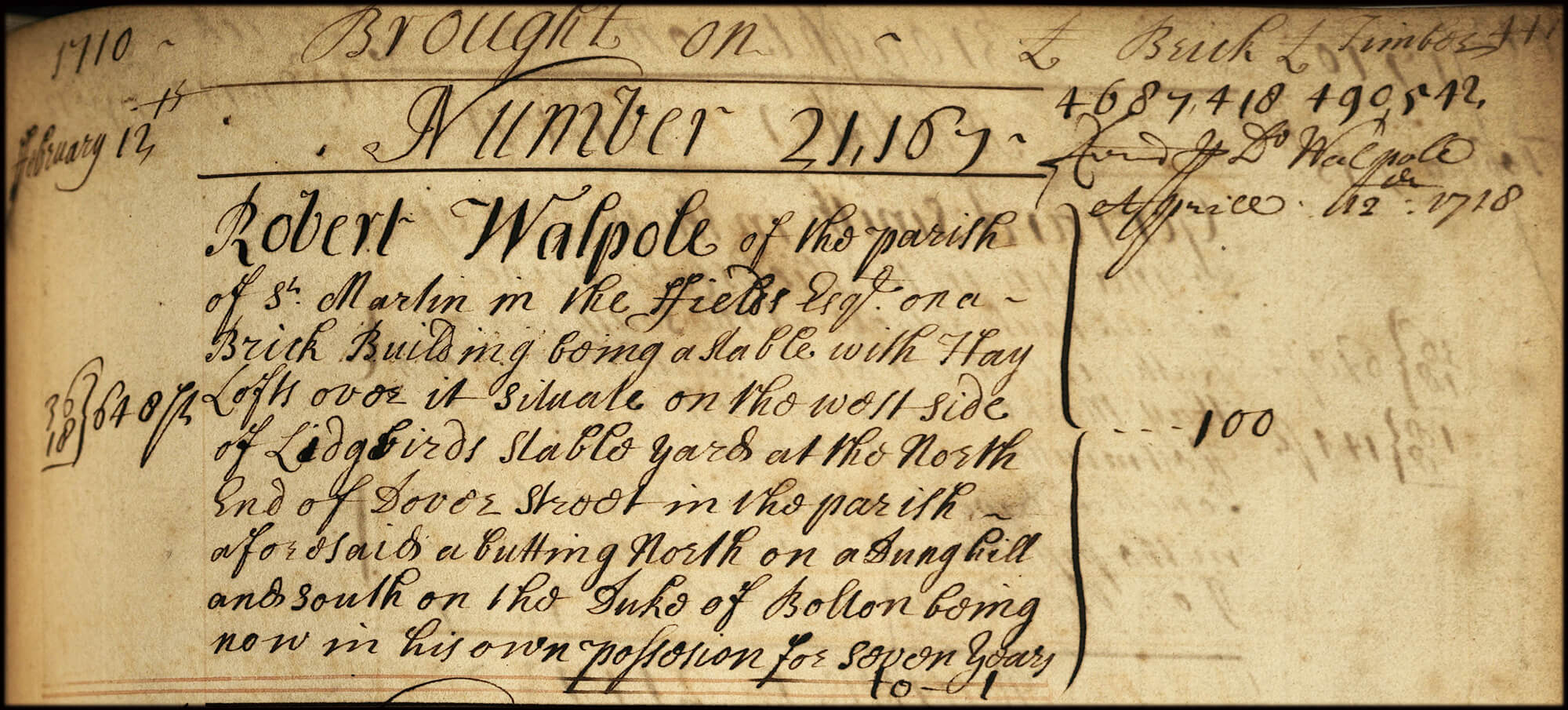

The policy book of the Hand in Hand read like a “Who’s Who” of the time, with notable figures among its client base, including:

Robert Walpole, Britain’s first Prime Minister

Sir Isaac Newton, the scientist famous for his laws of gravity and motion

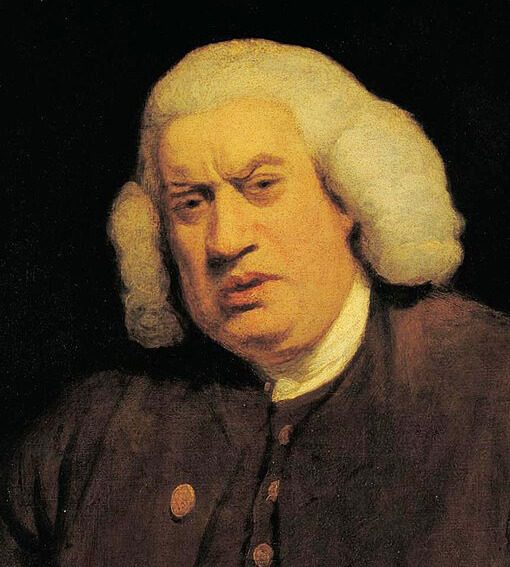

Samuel Johnson, the essayist and playwrite

Mr Sotheby and his competitor Mr Christie, both auctioneers

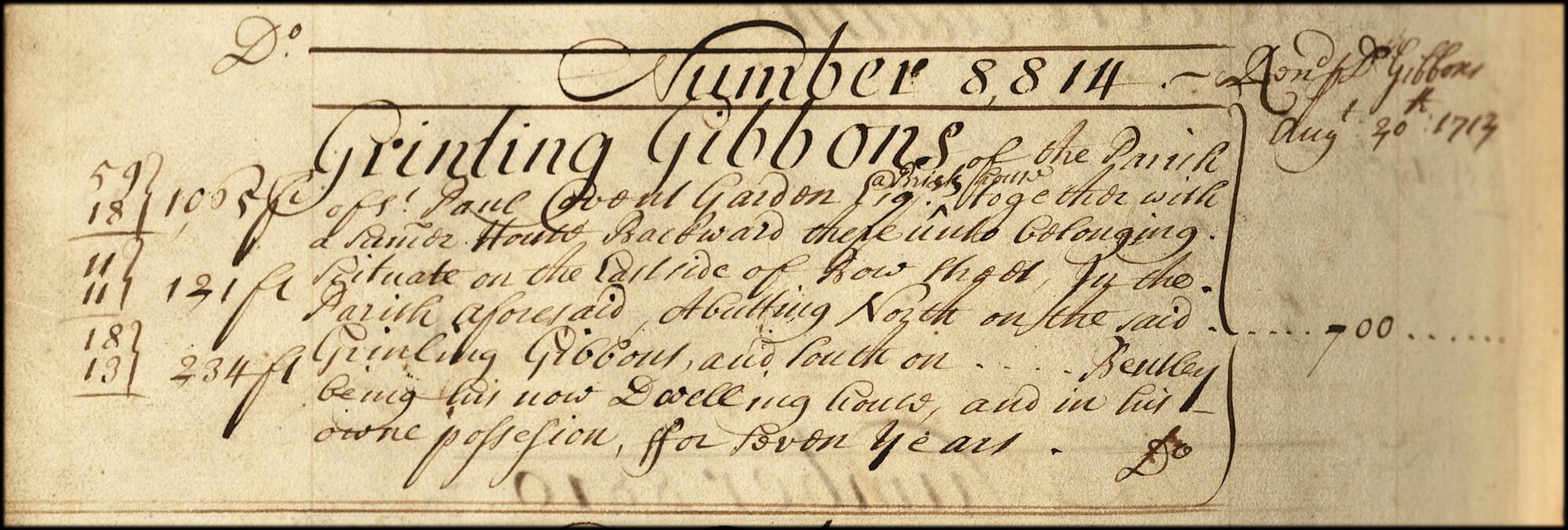

Grinling Gibbons, known as the finest wood carver of his age

Sir Godfrey Kneller, portrait artist

Members of the Kit Kat Club… and the list goes on.

Famous buildings

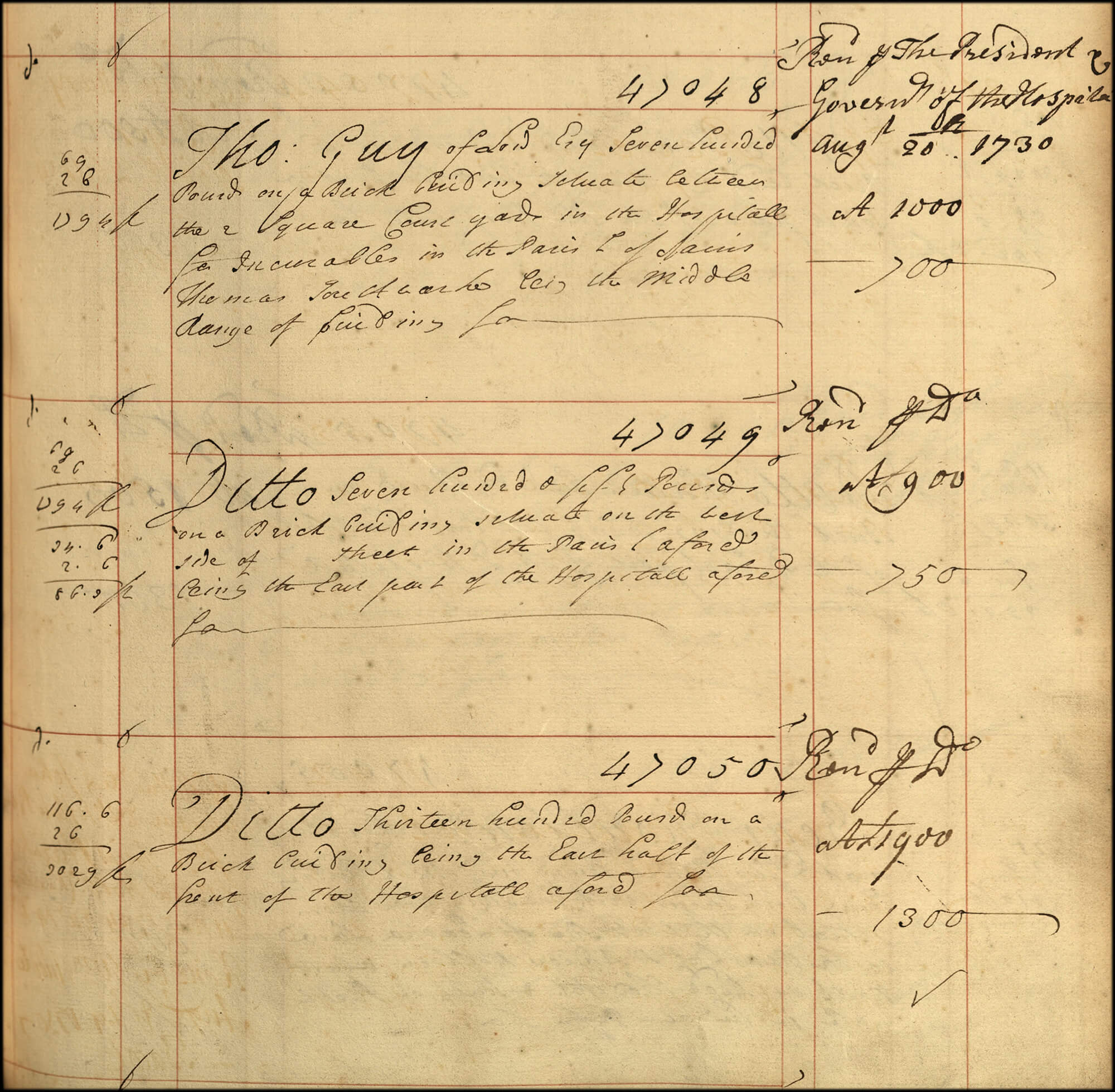

The Hand in Hand insured many important buildings of the day including coffee shops, theatres and hospitals:

No. 1, London – the home of the Duke of Wellington

Guy’s Hospital

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Opera House, Haymarket

The British Museum

Samuel Whitbread’s first brewery at Chiswell Street

In May 1758. the Hand in Hand insured the temporary London Bridge following the destruction of the original temporary bridge in a fire.

First Claim - 'Damnifyed by fire'

On 11 May 1697, the Hand in Hand’s first loss of one pound twelve shillings, was settled on two houses in St Stephen’s Alley in the parish of St Margaret’s.

The policy had been taken out two months earlier by John Ambler, a gardener, on properties in possession of Mr Randall and Mr Hoseard.

According to the company’s minutes the money was for repairs to Mr Randall’s and Mr Hoseard’s houses in St Stephen’s alley in the parish of St Margaret’s Westminster “being damnifyed by fire on the 16th day of April 1697.”

Return to start

Hand in Hand objects

View slides

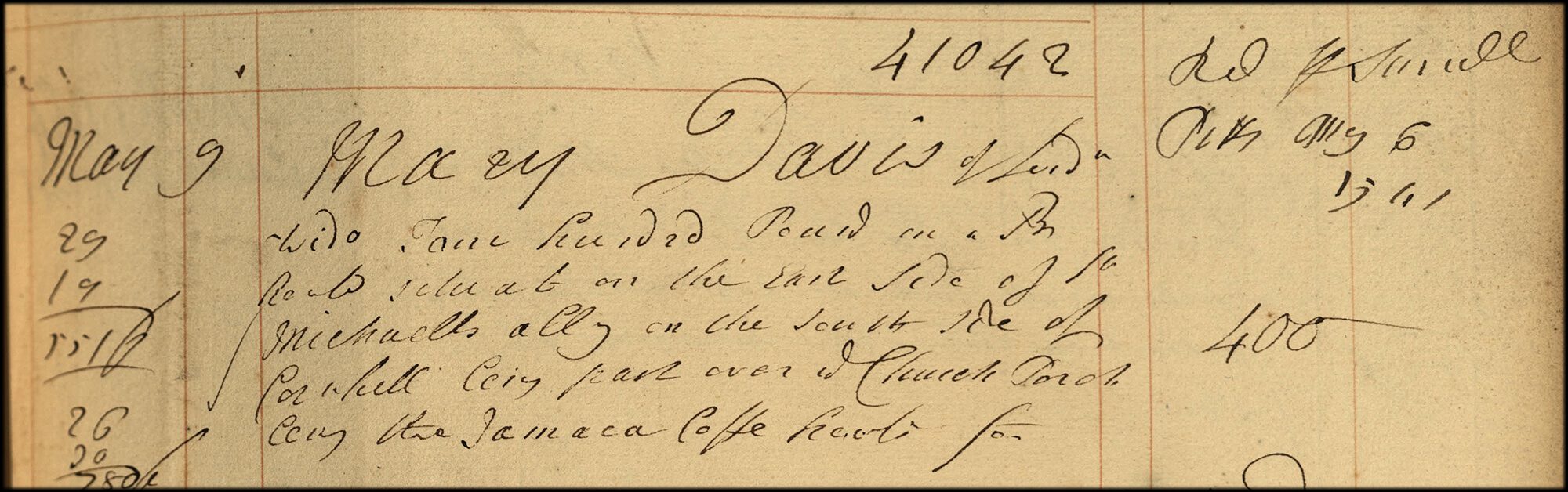

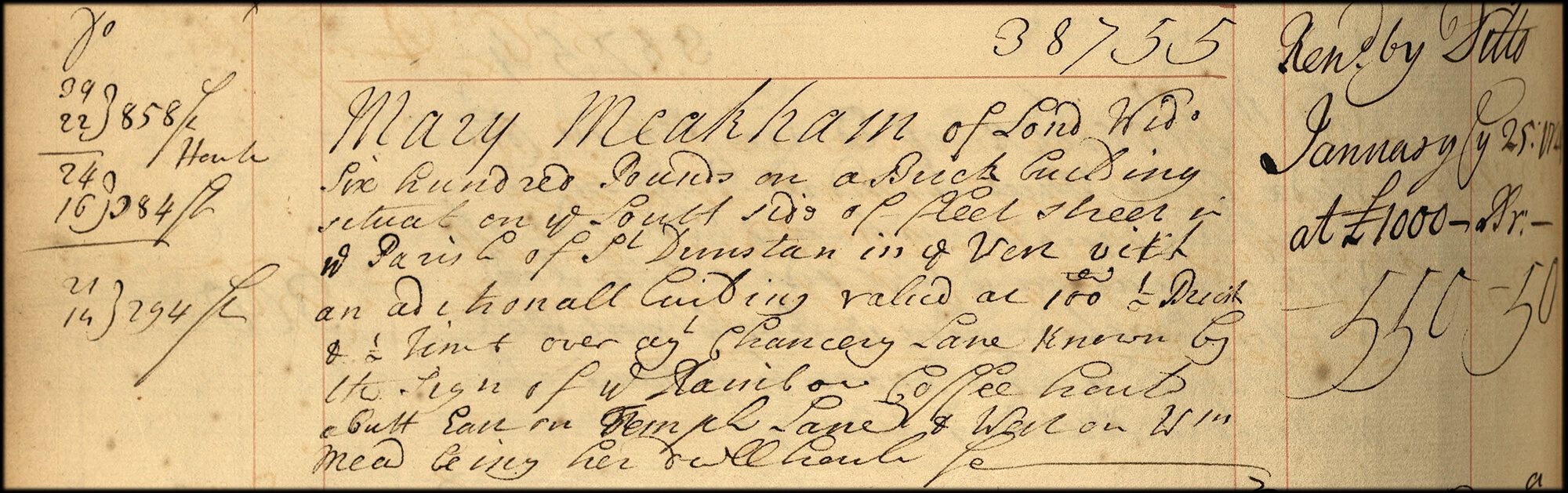

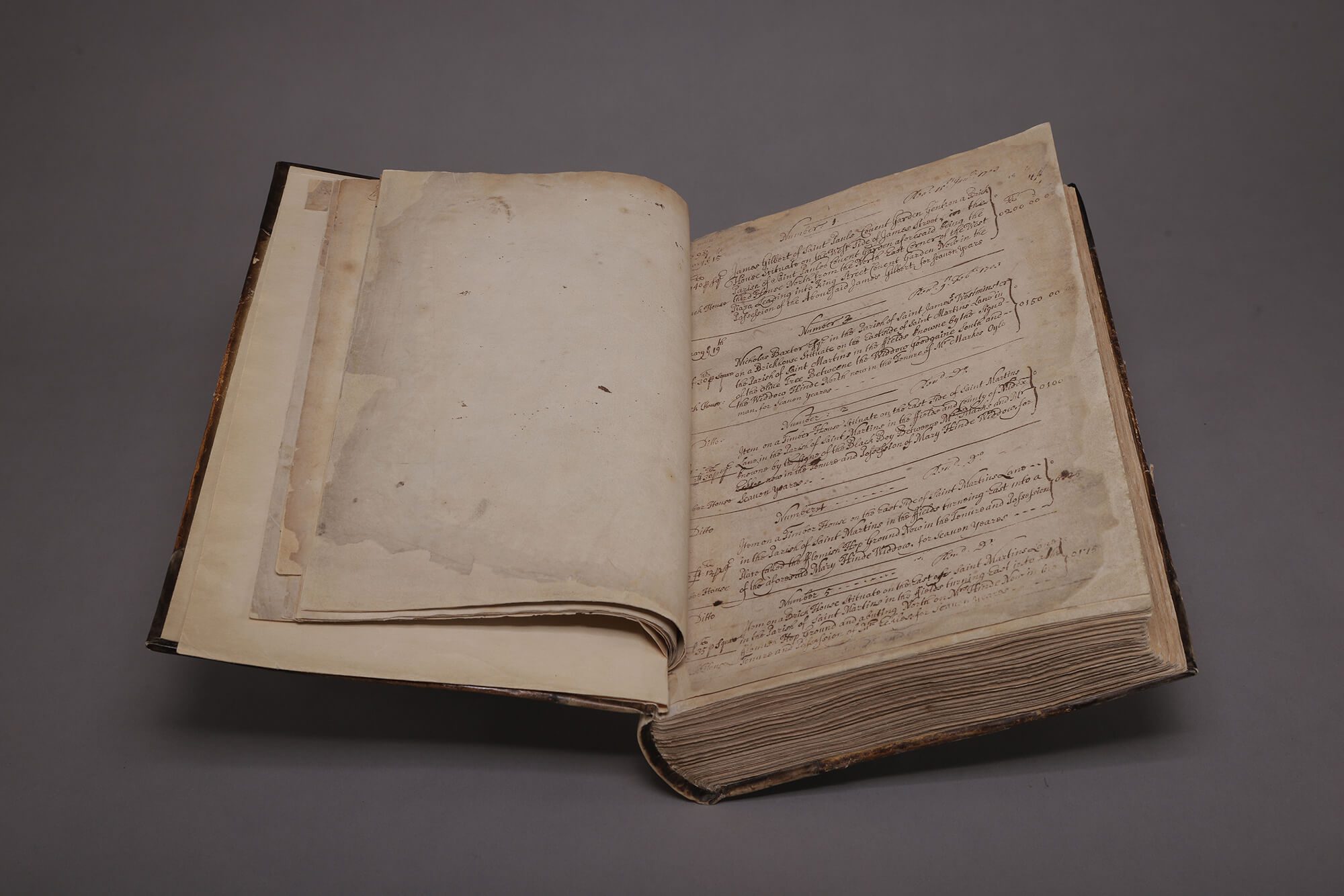

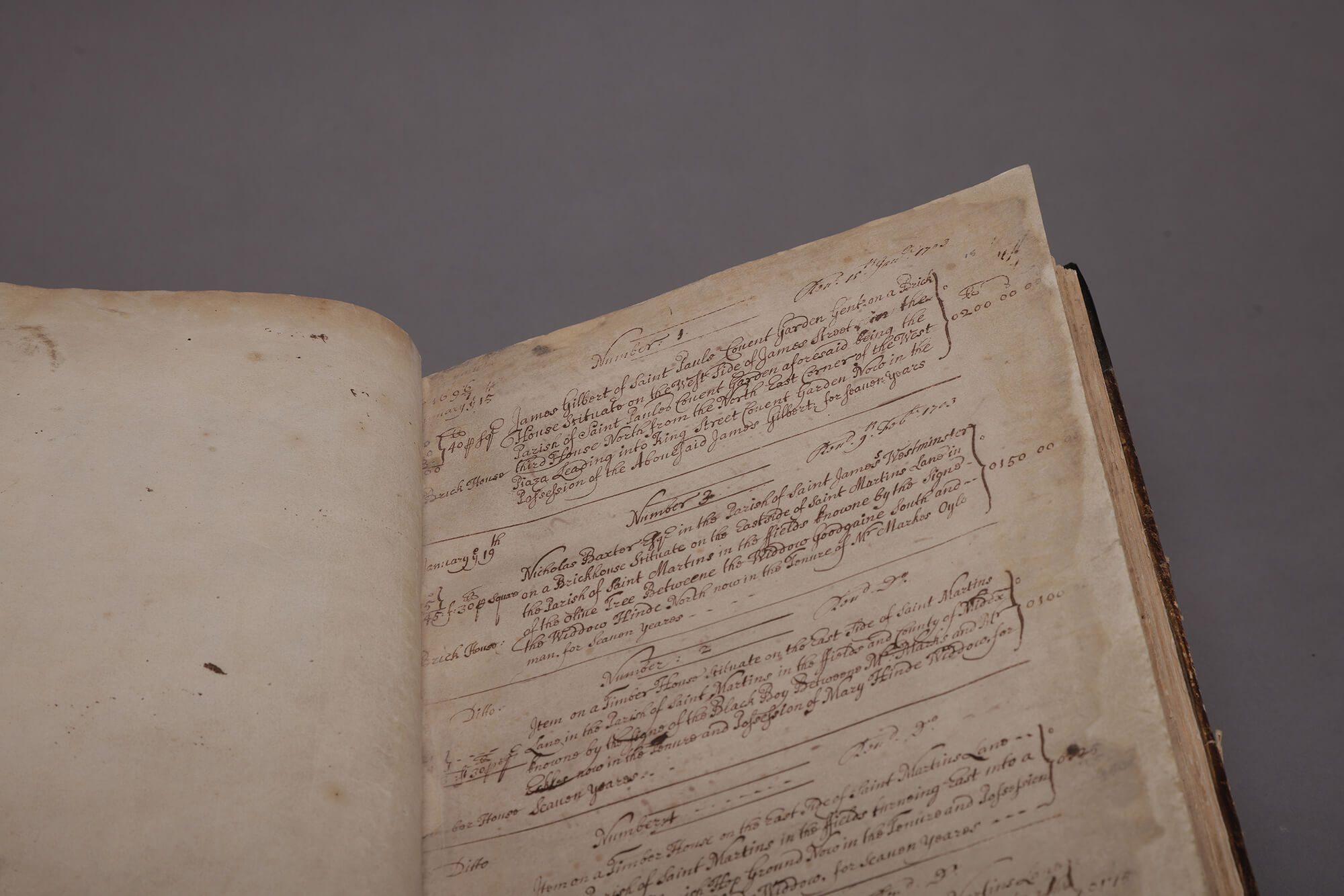

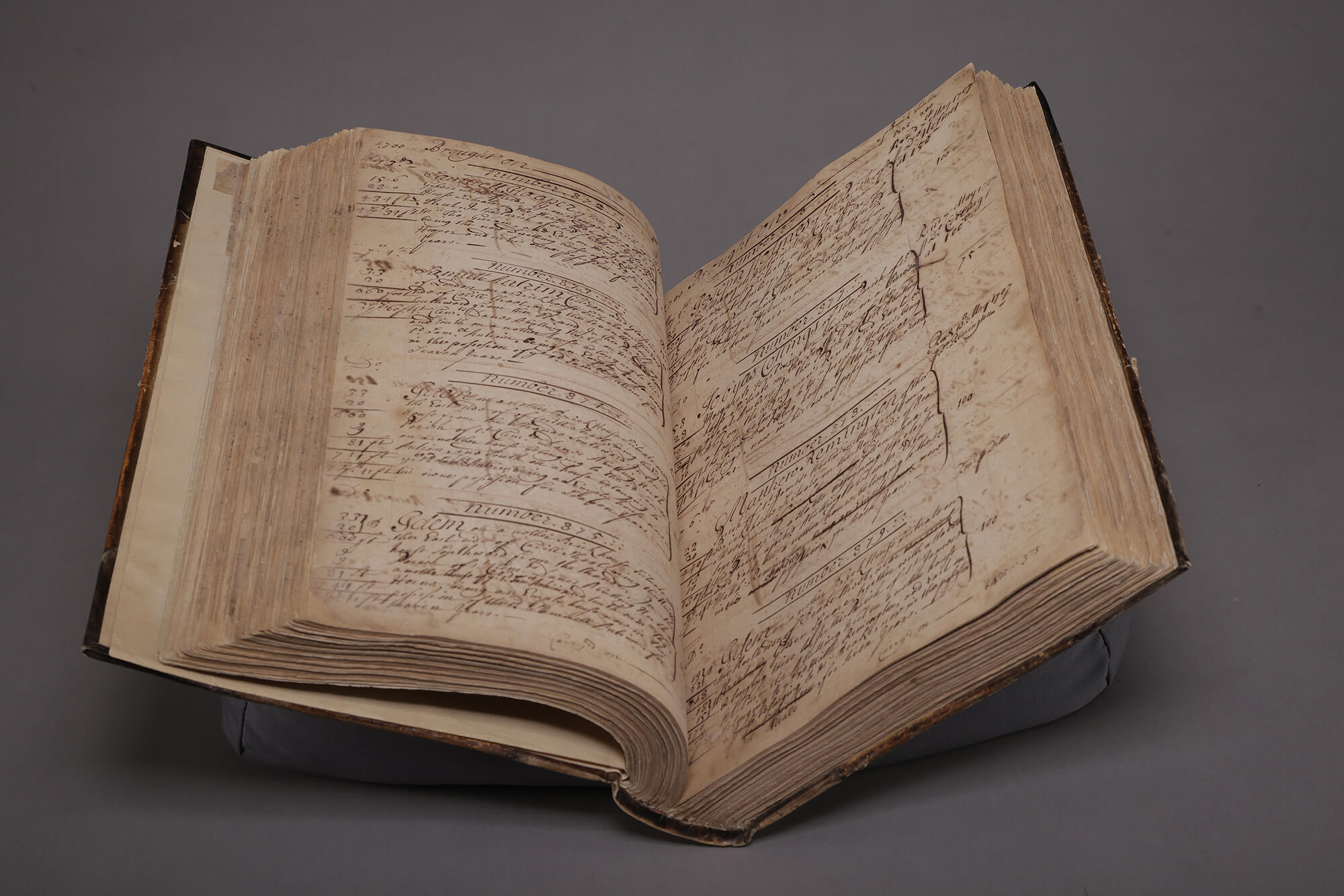

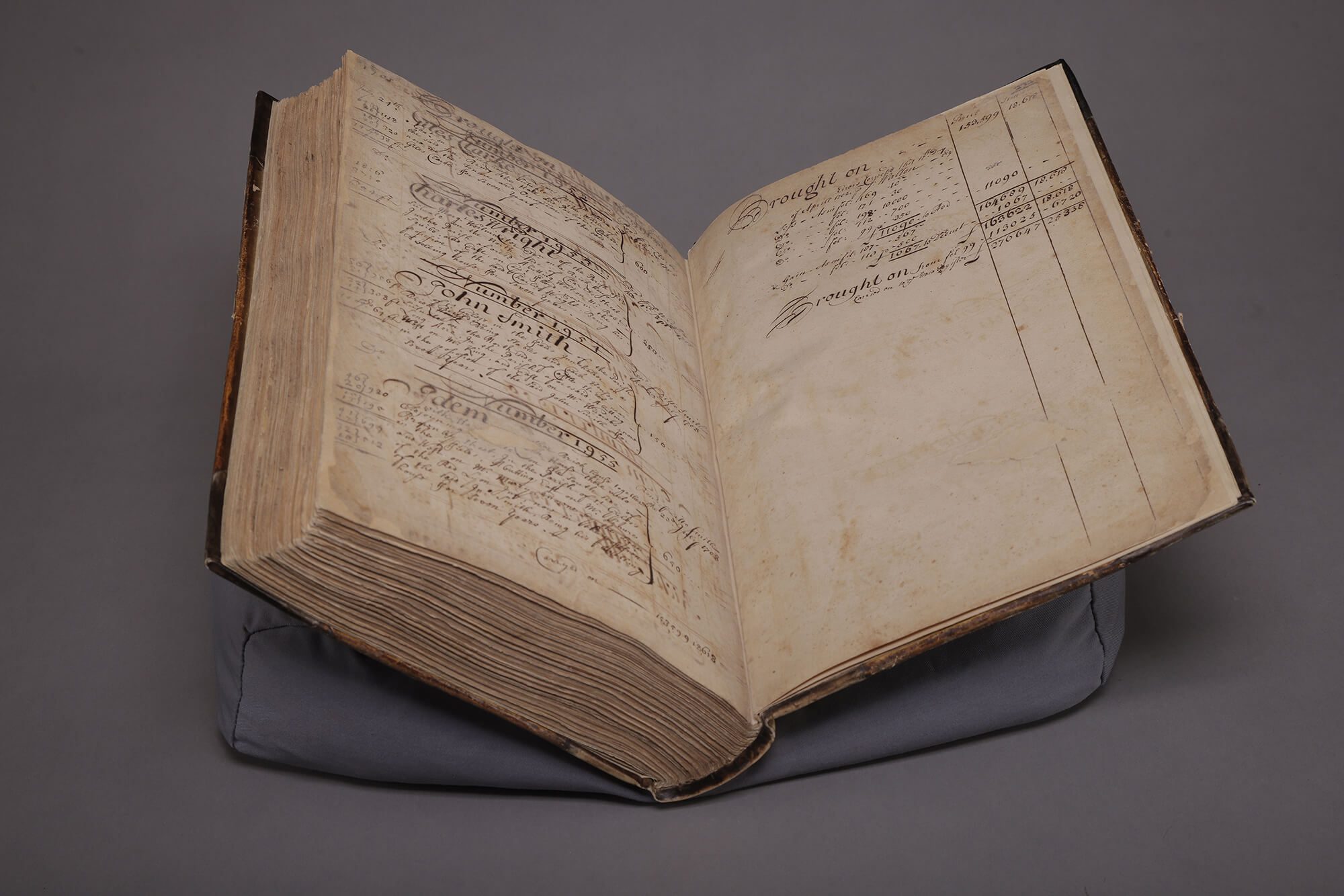

Policy register

An insurance Policy Register is a list of all insurance policies held by the company as well as any important information about each policy. This could include occupation and address of the policy holder as well as the type of construction and value of the property, cover type, premium paid and expiry date.

Policy Number 1 was taken out on 15 January 1697 by James Gilbert of St Paul’s Covent Garden on a brick house on the west side of St James Street.

Fire mark

This fire mark relates to a policy taken out by John Martin of London Gent on 25/11/1718. It was for £200 on a brick house “situated on the east side of Beare Lane in the parish of St Allhallows Barkin, being the 3rd house northward from Thames Street and part over the passage into Horn Court abutt north on the passage into Gloucester Court and south on the said John Martin in possession of Thomas Banberry.” It was renewed by Charles Jenner in 1725.

Hand in Hand firemark no 37840, 1718

Foreman's Staff

In 1704, it was decided that in order to give more prominence to the General Meeting marches, a “handsome Staffe, with a silver head, with the hand in hand and crown” be provided.

This staff was carried by the foreman of the brigade on all future marches and at all official functions.

All fire brigades would parade a five mile route around the Cities of London and Westminster on the days of their companies general meetings.

Most brigades marched with music and all dressed in their bright uniforms. It was a great spectacle for the local inhabitants and quickly the fire offices recognised the publicity value of this.

In 1789, the Union required its firemen on the march to distribute copies of “an account of the design and state of the Office” as part of an effort to stem declining membership.

The brigades were also used as a special constabulary at other public ceremonies such as the Lord Mayor’s procession.

The decorative silver head of the parade staff

Iron Chest

It was necessary to find a method for ‘safe keeping for items’ of value held by the office, such as the Exchequer Bills and petty cash.

In March 1698 it was therefore agreed that an iron chest be ordered with three locks for “ye keeping and preserving all Money Writeings and other effects”.

The key to the main lock was kept by the Treasurer and the other two keys were held by nominated Directors. Unfortunately it became something of a problem opening the chest, as it proved difficult getting all three key-holders present at the weekly meetings.

To avoid the problem with attendance, Directors signed an agreement that every time they failed to meet the weekly meeting they would pay a forfeit of one shilling to the office.

This iron chest was ordered by the Hand in Hand board in March 1698.

Buckets

Firefighting equipment used by watermen was still very primitive and there was the added problem of the availability of water.

In the event of fire, water would be passed in leather buckets by hand along a human bucket chain from the water source to the cistern of the manual fire pump.

Parishes were legally obliged to provide fire plugs – the forerunner of the fire hydrant. The Hand in Hand sought to prosecute church wardens when they failed in their responsibilities.

The 18th century bucket was formed from soaked leather which was stretched over a mould, hand sewn and then lined with pitch to make it waterproof. A leather handle completed the bucket. This was the only means available to the watermen for carrying water in the early 18th century. With these they extinguished small fires and filled the cisterns of the few parish fire engines which were in working order and able to be brought to the fire.

Return to start

Hand painted leather bucket

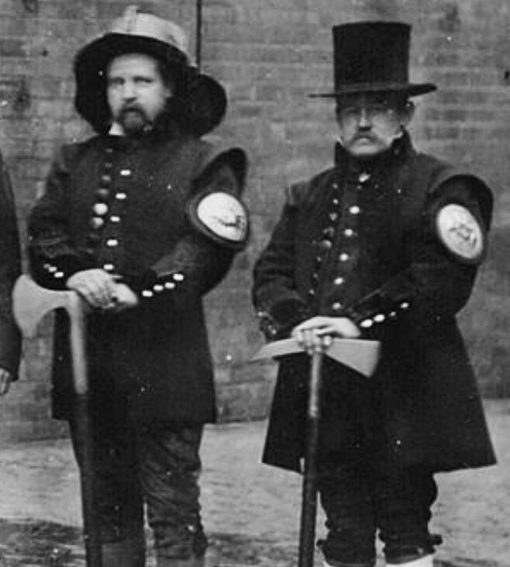

Hand in Hand Fire fighters

“The several insurance offices… Have each of them a certain set of men, who they keep in constant pay… these men make it their business to be ready at call, all hours and night and day, to assist in case of fire… These they call fire-men, but with an odd kind of contradiction in the title, for they are really most of them water-men.”

Daniel Defoe, Tour through Great Britain, 1724

View slides

Waterman insurance fire fighters

The desperate need for organised fire brigades was obvious, especially for those who remembered the Great Fire.

Using watermen as firefighters made sense as they were strong, tough men not afraid of danger and there were many to choose from. They had also already proven their abilities working for Barbon’s Fire Office.

Watermen working for the Hand in Hand as firefighters, attended fires as needed in varying numbers and were paid for the length of time they were present at the scene.

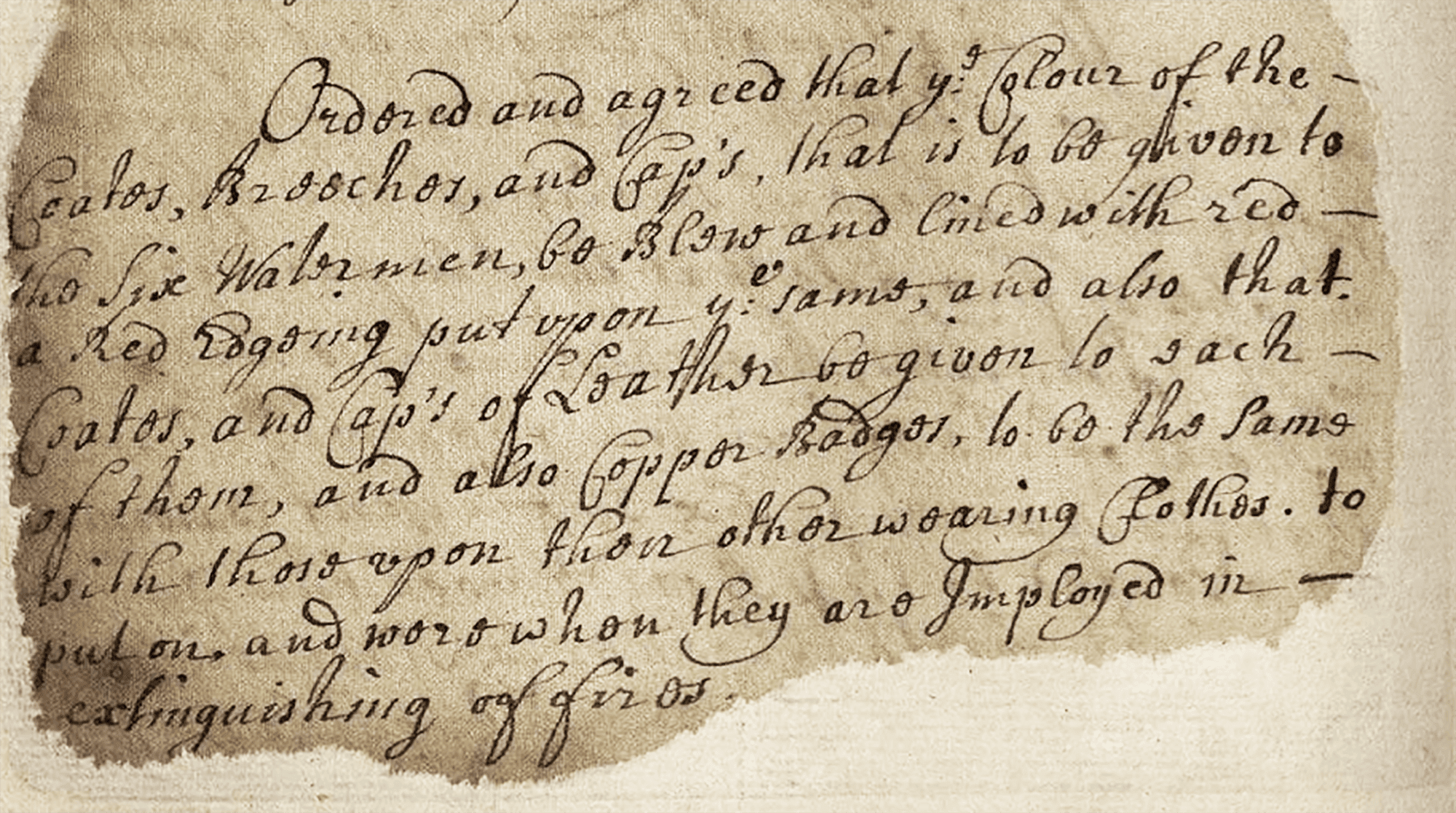

Each man was provided with a uniform consisting of cap, coat, breeches and an arm badge – all in the mark of the office.

The firefighting uniform was to be kept with them at all times – as were the tools. Firefighting tools consisted mainly of hatchets or pole axes and also preventers – large hooks on a long staff used to pull burning material off the roofs of buildings.

By 1707 the strength of the Hand in Hand brigade had reached 26.

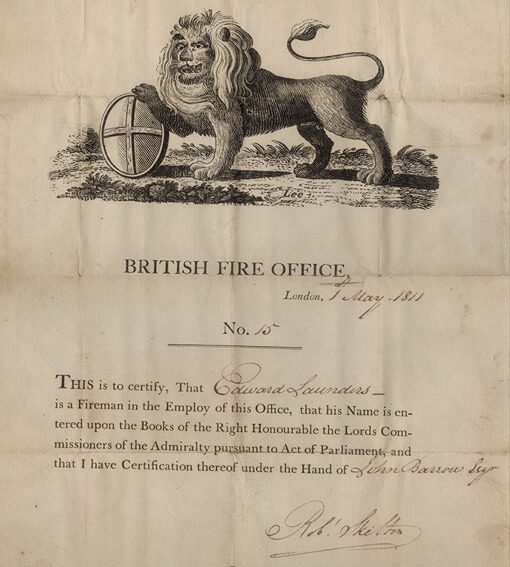

Press gang exemption

Press gangs were groups of soldiers or sailors sent out to look for suitable strong, young men to coerce into naval or military service – often by drunken tricks or violent means.

Watermen would have been particularly attractive for ‘pressing’ because they were known to be fit, strong and already comfortable and able to work on water.

The fire office firefighters were issued with a certificate. which they carried with them to protect them from the press gangs, with a few exceptions, this was usually effective.

One of the main reasons watermen were so attracted to becoming firefighters for the Fire Offices was that up to 30 firefighters from each company were exempt from the press gangs (provided that their names had ben registered with the Admiralty) – something legalised on the instigation of the Hand in Hand. This was the first example of the Hand in Hand taking the lead in bringing about a change in the laws of the country.

Press gangs continued to work until 1815 (and the end of the Napoleonic wars), at this time 75% of the Navy’s men had been press-ganged or ‘impressed’.

Example press gang exemption certificate, courtesy of Ron Long's collection.

Loss of life

Fighting fires has always been dangerous and the first recorded injury to a Hand in Hand fireman was in 1703. The Directors were sympathetic to the fact that in those days inability to work through injury meant that no income whatsoever was available to the man or his family.

In this case, they paid the man 20 shillings for an injury sustained fighting a fire at Wapping. This was the first of regular payments to the watermen for loss of work due to injury. Where necessary, they also paid surgeons’ and physicians’ bills.

The first fatality was in 1730 when two of the Hand in Hand’s firefighters were killed by a house falling in Fetter Lane. The Directors agreed to pay for a shroud and coffin for both men, compensation was also paid to the families of the fire fighters.

It later became the practice for the office to pay surgeons’ bills and wages if the men were laid up.

Further minute and bill notes recorded:

06/07/1703

Samuel Ambler or Amble given 20s for loss of time due to being hurt in Wapping fire at execution dock.

(He had been appointed 29/10/1700 aged 38 in May 1708. Ployed at Black Lyon Stayres)

09/04/1706

Thomas Newstead was paid £1 10s for loss of time after injury at Shore Lane Fire towards the support of his family

(He had been appointed 26/09/1699 Ploying at Salisbury Stairs aged 40 in May 1708.)

16/09/1707

George Harrington was paid £1 5s being hurt by falling timber at a fire.

(Aged 26 in May 1708. Ploys at Strand bridge. Made engineer and given badge No. 2 12/06/1718.)

02/03/1707/8

Bill for £1 9s 6d for surgeons ‘Chirurgions’ for attention to the watermen hurt in Strand fire – also each injured man received 2s 6d for each day lost.

(Fire at Strand 14 Feb cost £4, 451 3s 11d)

23/04/1706

Timothy Alderson was paid £1 for physick and loss of time after fire in Shore Lane.

27/03/1711 his hand was injured and treated by surgeon.

22/10/1706

Edward or Edmund Earle was given 30s for his good service at King Street and an injury sustained.

13/01/1729/30

Pay a fireman 5 guineas for leaving his house which was in danger to fight other fires whereby his house caught fire and his goods were pillaged.

07/04/1730

2 firemen killed by a house falling in Fetter Lane

Company pasy for shroud and coffin

27/04/1730

Anonymous lady gives a guinea to be divided among the widows of the two firemen killed also 30 guineas sent by East India Company and 30 guineas from the Sun Insurance.

Company paid £25 to each family.

13/08/1734

William Abrathat was killed in fire at Temple Bar.

The company gave £20 give to his widow who had 2 children and was pregnant.

07/01/1766

Resolved that an allowance be made towards placing out in the World when they are of a proper age, Margaret Pettit aged about four years and Ann about one year and a half the daughters of William Pettit, a fireman of this Office who died in the Hospital after the breaking of his Leg at the fire in Bishopsgate Street.

Early waterman fire fighter

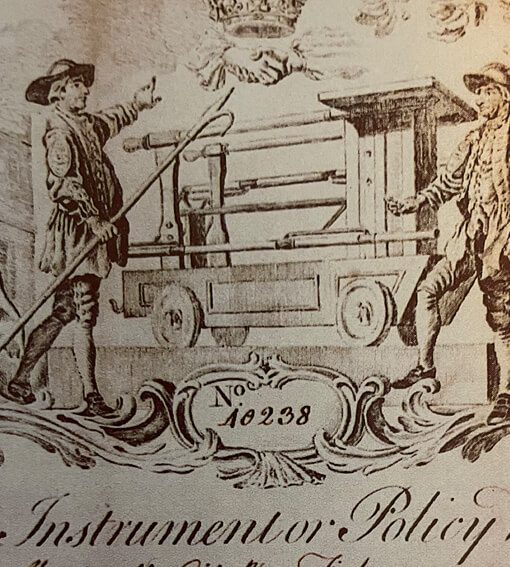

Manual Fire Engines

In 1716, the Hand in Hand ordered its first fire engine in the smallest size for which they paid £15.

In April 1718 it was decided that “Mr Keeling do make a large Engine for ye use of ye office… and that it be left to him to make as good an one as possible.” John Keeling of Blackfriars was one of the earliest manufacturers of manual fire engines. The office paid Keeling £35 for the engine and 40 yards of leather hose.

In 1723, the Board decided they should consider the possibility of purchasing a new manual fire engine and consulted Richard Newsham, a pearl button maker, who was granted a patent to make a “new water engine for quenching and extinguishing of fires” in 1721.

A 40 gallon engine was purchased from Newsham for £30 and an 80 gallon engine for £40. At that time Newsham was comparatively unknown. By 1725, Newsham was the leading fire engine manufacturer of his day.

Taking early engines to the fires was no easy task. The early models had small solid timber wheels that were unsuitable for hauling rapidly over the cobbled streets of London. By 1729, horses were being used, probably to pull carts carrying the smaller engines.

Newsham manual fire engine featured on an Hand in Hand Policy document

Hand in Hand Objects

Tools for Firefighting recognition and reward. Objects courtesy of the Aviva Group Archive, photography by Lloyd Sturdy.*

Fireman's badge

A silver arm badge was worn on the upper half of the left arm of each firefighter for every occasion. Each badge bore the arms of the waterman's company, the Arms of the City of London and a number. The number helped to establish the men as bona fide insurance firemen and helped members of the public to identify them for complaint or praise.

In 1699, the Hand in Hand decided their arm badges would be 6x5 inches and made in sterling silver. The cost of £2 4s 6d for each badge represented a small fortune to the watermen who wore them.

Read more...Fireman's badge

A silver arm badge was worn on the upper half of the left arm of each firefighter for every occasion. Each badge bore the arms of the waterman's company, the Arms of the City of London and a number. The number helped to establish the men as bona fide insurance firemen and helped members of the public to identify them for complaint or praise.

In 1699, the Hand in Hand decided their arm badges would be 6x5 inches and made in sterling silver. The cost of £2 4s 6d for each badge represented a small fortune to the watermen who wore them.

Director's token

Director's from the Hand in Hand would often attend the fires that took place and sought to help direct firefighting efforts. In order that they could prove their status to the firefighters director's tokens were produced in solid silver.

This commemorative box has used two of the silver director's tokens as a decorative feature.

Read more...Director's token

Director's from the Hand in Hand would often attend the fires that took place and sought to help direct firefighting efforts. In order that they could prove their status to the firefighters director's tokens were produced in solid silver.

This commemorative box has used two of the silver director's tokens as a decorative feature.

Payment token

Once at the scene of a fire, firefighting watermen usually enlisted the help of onlookers to work the engines. For every shift, members of the public who helped were each given a token, which could later be exchanged for a beer at a local tavern or cash when presented to the fire office.

This payment token belonged to the Union.

Read more...Payment token

Once at the scene of a fire, firefighting watermen usually enlisted the help of onlookers to work the engines. For every shift, members of the public who helped were each given a token, which could later be exchanged for a beer at a local tavern or cash when presented to the fire office.

This payment token belonged to the Union.

More Payment Tokens

The tokens were kept on a chain or piece of string, which is why all payment tokens have a hold punched in them.

To quench the thirst of volunteers pumping the manual fire engines, beer flowed quite freely at some fires. The bills for this would have created some interesting conversations back at the insurance fire offices.

According to reminiscences in the Norwich Union staff magazine of 1941, after one fire in the 1880s the bill for beer came to £38 – a note of thanks from Norwich Union asked if beer had been used to extinguish the flames.

*Objects and images courtesy Ron Long's collection.

More Payment Tokens

The tokens were kept on a chain or piece of string, which is why all payment tokens have a hold punched in them.

To quench the thirst of volunteers pumping the manual fire engines, beer flowed quite freely at some fires. The bills for this would have created some interesting conversations back at the insurance fire offices.

According to reminiscences in the Norwich Union staff magazine of 1941, after one fire in the 1880s the bill for beer came to £38 – a note of thanks from Norwich Union asked if beer had been used to extinguish the flames.

*Objects and images courtesy Ron Long's collection.

Foreman's Passes

These passes or tokens (Hand in Hand, The Union) were used to signify a fire fighter's authority.

The Hand in Hand token was in use until relatively recently as a 'handing-over' token at change of watch at a London fire brigade station.

*Objects and images courtesy Ron Long's collection.

Foreman's Passes

These passes or tokens (Hand in Hand, The Union) were used to signify a fire fighter's authority.

The Hand in Hand token was in use until relatively recently as a 'handing-over' token at change of watch at a London fire brigade station.

*Objects and images courtesy Ron Long's collection.

Return to start

New Fire Offices

Westminster fire mark

Courtesy of the Ron Long collection

View slides

The South Sea Bubble

The growth of new fire offices was halted in part due to the South Sea Bubble Act of 1720, which prevented new joint-stock companies from forming without a royal charter.

The South Sea Bubble was possibly the world’s first financial crash. The name describes the enormous success of the South Sea Company founded in 1711, which grew rapidly during the 1710s, thanks to a frenzy of investment and insider trading, before dramatically collapsing in September 1720.

Losses were widespread as many households suffered and some were ruined. Those known to have lost a lot of money in the crash include famous names such as Sir Isaac Newton and the author of Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift.

In June 1720, towards the height of the success of the company, the Bubble Act was passed by government which prohibited the creation of joint-stock companies without Royal Charter, effectively giving the South Sea Company a monopoly.

Just two insurance companies were created for the purposes of marine insurance: the Royal Exchange Assurance Corporation and the London Assurance Corporation, which remained the only London insurers in Britain until 1760, the ban was abolished in 1825.

Trading on the street, with the latest news of the South Sea Company

London Insurance Companies

Insurance Fire Offices that opened in London during 1696 - 1760

Words courtesy Brian Wright, objects courtesy Ron Long

Hand in Hand 1696 - 1905

The Hand in Hand would one day by bought by the Commercial Union, which became part of the Norwhich Union and then AVIVA.

Aviva sometimes references it's 365 years of history, which is linking back to their origins with the Hand in Hand.

Read more...Hand in Hand 1696 - 1905

The Hand in Hand would one day by bought by the Commercial Union, which became part of the Norwhich Union and then AVIVA.

Aviva sometimes references it's 365 years of history, which is linking back to their origins with the Hand in Hand.

Sun Fire Office 1714 - 1907

In 1710, the Sun Fire Office became the first fire office to introduce fire insurance for contents as well as homes and was the first to take its business outside of London through a network of agents - though few were appointed before 1720. In the following decade sales outlets quickly became established in the provinces and the Sun enjoyed a near monopoly in many places before the 1780s.

The use of a sun as the company mark was possibly chosen because the founder Charles Povey was interested in astronomy. The straight and wavy rays represent heat and light.

Read more...Sun Fire Office 1714 - 1907

In 1710, the Sun Fire Office became the first fire office to introduce fire insurance for contents as well as homes and was the first to take its business outside of London through a network of agents - though few were appointed before 1720. In the following decade sales outlets quickly became established in the provinces and the Sun enjoyed a near monopoly in many places before the 1780s.

The use of a sun as the company mark was possibly chosen because the founder Charles Povey was interested in astronomy. The straight and wavy rays represent heat and light.

The Union Fire Office 1714 - 1907

1714 saw the formation of the Union Fire Office which insured a household’s contents, including 'merchandise, movable goods, ware, utensils and implements in trade, household goods and furniture', The Union worked in close co-operation with the Hand in Hand, which insured only buildings. Many directors of the Union were also on the board of the Hand in Hand and encouraged policyholders to insure their buildings with them. The Union agreed not to insure buildings until the Hand in Hand began to insure goods in 1805.

Liveried porters were employed by the Union to remove goods from burning and endangered houses until 1806, when a fire engine was purchased and the porters reorganised into a fire brigade.

Read more...The Union Fire Office 1714 - 1907

1714 saw the formation of the Union Fire Office which insured a household’s contents, including 'merchandise, movable goods, ware, utensils and implements in trade, household goods and furniture', The Union worked in close co-operation with the Hand in Hand, which insured only buildings. Many directors of the Union were also on the board of the Hand in Hand and encouraged policyholders to insure their buildings with them. The Union agreed not to insure buildings until the Hand in Hand began to insure goods in 1805.

Liveried porters were employed by the Union to remove goods from burning and endangered houses until 1806, when a fire engine was purchased and the porters reorganised into a fire brigade.

The Westminster 1717 - 1906

The Hand in Hand operated from Tom's Coffee House in St Martin's Lane, Westminster, and had members from both the City of Westminster and the City of London. London members found it inconvenient to travel to Westminster for office meetings and called for the removal of its office to London. The move was opposed by Westminster members, but they were overridden and an office was opened at Snow Hill in the City of London.

This greatly upset the members from Westminster and in 1717 they seceded from the Hand in Hand, and set up their own mutual insurance scheme from a single room at Tom's. Eighteen Thames watermen were employed as part-time firemen, paid for each attendance at a fire. They were supplied with helmets, axes and hooks. Then in 1720, with uniforms and their first fire engine.

Read more...The Westminster 1717 - 1906

The Hand in Hand operated from Tom's Coffee House in St Martin's Lane, Westminster, and had members from both the City of Westminster and the City of London. London members found it inconvenient to travel to Westminster for office meetings and called for the removal of its office to London. The move was opposed by Westminster members, but they were overridden and an office was opened at Snow Hill in the City of London.

This greatly upset the members from Westminster and in 1717 they seceded from the Hand in Hand, and set up their own mutual insurance scheme from a single room at Tom's. Eighteen Thames watermen were employed as part-time firemen, paid for each attendance at a fire. They were supplied with helmets, axes and hooks. Then in 1720, with uniforms and their first fire engine.

London Assurance 1720 - 1965

The London Assurance started as a marine insurance company, obtaining its Royal Charter in the midst of the South Sea Bubble crisis in 1720. In 1721 a second charter was obtained to extend its activities to life and fire insurance in England, Wales, Ireland and 'all other parts of His Majesty's Dominions beyond the Sea'. Agents were appointed from September 1721 in various parts of England and with one in Ireland.

The company had to move premises in March 1748 when its offices were destroyed in the Cornhill Fire. They first moved to Birchin Lane and later to King William Street. The image of Britannia in the fire mark represents the 'spirit of Britain'. Her shield bears the arms of the City of London and she holds an Irish harp.

Read more...London Assurance 1720 - 1965

The London Assurance started as a marine insurance company, obtaining its Royal Charter in the midst of the South Sea Bubble crisis in 1720. In 1721 a second charter was obtained to extend its activities to life and fire insurance in England, Wales, Ireland and 'all other parts of His Majesty's Dominions beyond the Sea'. Agents were appointed from September 1721 in various parts of England and with one in Ireland.

The company had to move premises in March 1748 when its offices were destroyed in the Cornhill Fire. They first moved to Birchin Lane and later to King William Street. The image of Britannia in the fire mark represents the 'spirit of Britain'. Her shield bears the arms of the City of London and she holds an Irish harp.

Royal Exchange 1720 - 1968

The Royal Exchange, founded in 1720 took its name from the location of its offices at the Royal Exchange in London. The company first received a Royal Charter to write marine insurance under the Bubble Act.

In May 1721 adverts showed that the company employed '14 watermen to work the engines, 21 other watermen provided with proper instruments to extinguish fires, and also 21 porters'.

The first agent was appointed in May 1721 in Berkshire, and a Dublin agent was appointed in 1722. The agency network was not large, with only fifteen provincial agents in 1758 and 44 in 1775, although by 1805 there were 315 (including three in Ireland).

Read more...Royal Exchange 1720 - 1968

The Royal Exchange, founded in 1720 took its name from the location of its offices at the Royal Exchange in London. The company first received a Royal Charter to write marine insurance under the Bubble Act.

In May 1721 adverts showed that the company employed '14 watermen to work the engines, 21 other watermen provided with proper instruments to extinguish fires, and also 21 porters'.

The first agent was appointed in May 1721 in Berkshire, and a Dublin agent was appointed in 1722. The agency network was not large, with only fifteen provincial agents in 1758 and 44 in 1775, although by 1805 there were 315 (including three in Ireland).

Insurance Expert

New London Fire Offices and the South Sea Bubble

With Robin Pearson

Provincial Insurance companies

Insurance Fire Offices that opened outside of London during 1696 - 1760

Words courtesy Brian Wright, objects courtesy Ron Long

The Bristol Fire Office 1718 - 1837

The first insurance company to be founded outside London. Seven of the 40 co-partners were elected to a committee to run the day-to-day affairs, and an office was opened at Cooke's Coffee House. Within a year the number of co-partners had been increased to eighty, and new articles of agreement were drawn up which bound the co-partners and their descendants or assignees for a hundred years to 'become and be co-partners in insuring all and every such House and Houses, quantity or quantities of goods in the said City of Bristol' and the surrounding counties.

For some years the company had no competition and issued about 350 policies a year in its first ten years. The company maintained a fire brigade, but few details about it are known.

Read more...The Bristol Fire Office 1718 - 1837

The first insurance company to be founded outside London. Seven of the 40 co-partners were elected to a committee to run the day-to-day affairs, and an office was opened at Cooke's Coffee House. Within a year the number of co-partners had been increased to eighty, and new articles of agreement were drawn up which bound the co-partners and their descendants or assignees for a hundred years to 'become and be co-partners in insuring all and every such House and Houses, quantity or quantities of goods in the said City of Bristol' and the surrounding counties.

For some years the company had no competition and issued about 350 policies a year in its first ten years. The company maintained a fire brigade, but few details about it are known.

The Edinburgh Friendly Insurance Against Losses by Fire 1720 - 1847

After a number of serious fires in Edinburgh, Scotland's first fire insurance company was formed in 1720. A mutual company, named "The Friendly Society of the Heritors of Edinburgh and Suburbs thereof in Canon-gate, Leith etc. for a Mutual Insurance of their Tenements and Houses from Losses by Fire". Later shortened to the title above.

Initially, cover was offered only to residents of Edinburgh and its surrounds, but in 1767, the company having prospered, offered cover throughout Scotland. The cover was offered originally on buildings only but as the society expanded, cover was extended to include household goods, policies were issued and at this time the use of fire marks began.

Read more...The Edinburgh Friendly Insurance Against Losses by Fire 1720 - 1847

After a number of serious fires in Edinburgh, Scotland's first fire insurance company was formed in 1720. A mutual company, named "The Friendly Society of the Heritors of Edinburgh and Suburbs thereof in Canon-gate, Leith etc. for a Mutual Insurance of their Tenements and Houses from Losses by Fire". Later shortened to the title above.

Initially, cover was offered only to residents of Edinburgh and its surrounds, but in 1767, the company having prospered, offered cover throughout Scotland. The cover was offered originally on buildings only but as the society expanded, cover was extended to include household goods, policies were issued and at this time the use of fire marks began.

The Friendly Society of Glasgow 1720 - 1811

This society is believed to have been established just after the foundation of the Edinburgh Friendly Insurance Against Losses by Fire. Little is known of its progress, but it seems to have been reconstituted and renamed the Glasgow Fire Insurance Society in 1747, and then again in 1803 the Glasgow Fire Office.

The fire mark is based on the arms of Glasgow depicted on town seals of the thirteenth century. The tree represents a hazel tree from which St Kentigern, the patron saint of Glasgow and its first bishop, who died in 612, produced fire. The bird recalls the robin which he restored to life.

Read more...The Friendly Society of Glasgow 1720 - 1811

This society is believed to have been established just after the foundation of the Edinburgh Friendly Insurance Against Losses by Fire. Little is known of its progress, but it seems to have been reconstituted and renamed the Glasgow Fire Insurance Society in 1747, and then again in 1803 the Glasgow Fire Office.

The fire mark is based on the arms of Glasgow depicted on town seals of the thirteenth century. The tree represents a hazel tree from which St Kentigern, the patron saint of Glasgow and its first bishop, who died in 612, produced fire. The bird recalls the robin which he restored to life.

Evolution of fire marks

Fire mark designs remained relatively similar over the centuries, though of course variations occurred both in design evolution, size and the material that was used.

Fire marks that were originally produced in lead, might well end up being produced in a cheaper and less durable material such as tin.

All images and detail courtesy of Ron Long.

Spotting firemarks today

Although over the years thousands of fire marks have disappeared from public view, either by buildings being destroyed, fire marks being thrown away, given away or sold to private collectors; for those interested to see some, it’s good to know that there are some still out there.

Everyone will remember the moment they spot their first fire mark, so to help you find one, we have given you the following tips and pointers.

Tips and pointers:

1. Look up

Fire marks tend to be positioned quite high up on buildings, usually near the 1st floor windows, this is probably because they were expensive to produce and insurance offices would not want their marks to disappear and have to be replaced, so they fixed them fairly high up out of reach of those that didn’t have a ladder to hand.

2. Period property

You’re looking for older property, property of the period that the fire marks you seek existed in.

3. Near the river

In London some of the earlier fire marks can be found on property closer to the river, presumably as this was nearer to the network of the waterman fire fighters.

Return to start

Inspiring Benjamin Franklin

“Among the numerous luxuries of the table…coffee may be considered as one of the most valuable. It excites cheerfulness without intoxication; and the pleasing flow of spirits which it occasions…

…is never followed by sadness, languor or debility.”

Benjamin Franklin

View slides

A fan of the coffee houses

As a young man, Benjamin Franklin, the future writer, inventor and Founding Father of the USA stayed in London from 1724 for 18 months, working primarily as a printer’s apprentice.

During his stay in London, Franklin was a regular visitor at various coffee houses in London. He knew that different groups would meet in different coffee houses so would move in and out of them as his social network, to conduct business and to keep on top of all the news.

For instance, Franklin could keep up to date with news back home, by visiting the New England Coffeehouse in Threadneedle Street, where merchants and ship captains of New England met – or get more local news at the Virginia Coffeehouse near the Bank of England.

Benjamin Franklin also enjoyed playing chess at Tom Slaughter’s coffee house, the same location as where the Hand in Hand was formed; his post was delivered to the Pennsylvania coffee house in Birchin Lane EC3.

It is said that when he travelled by ship, he would take his own coffee beans with him in case those on the ship ran out.

Map of Cornhill highlighting some of the Coffee Houses (later destroyed in the Cornhill Fire in 1748)

Fire brigade

Whilst in London, Benjamin Franklin would have seen the literature promoting insurance fire offices and their fire fighters, he may even have printed the literature at the printer’s where he developed his trade.

Franklin was also a keen swimmer, showing off his mastery of swimming and acrobatic tricks in the river Thames and so he would have also been familiar with the Watermen and their work as fire fighters.

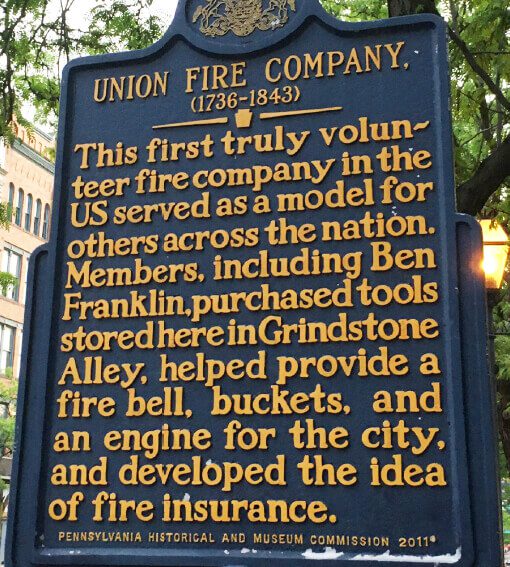

This must have been part of the inspiration, when in 1736 he and others formed the Union Fire Company in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was the first formally organised volunteer fire company of its kind in the US.

The Union Fire Company, also known as the “Bucket Brigade” was in part shaped after Boston’s Mutual Fire Societies. The difference between the fires societies of Boston and Franklin’s Union Fire Company was that the former protected its members only while the latter the entire community.

It’s said that the Union Fire Company ordered it’s first manual fire engines from the manufacturer John Bristow, who was based in London.

Union Fire Company

Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire

John Smith a respected merchant and a marine underwriter, was informed of the Cornhill Fire in London and given a map of the damage by a colleague, Joseph Saunders who had witnessed how fire insurance had flourished in London.

This is in part the inspiration for the formation in 1752 of the Philadelphia Contributionship by Benjamin Franklin and his fellow firefighters (from The Fire Union Company). John Smith was appointed the Treasurer and Joseph Saunders the Clerk for the company.

The company was modelled after the Contributors for Insuring Houses, Chambers or Rooms from Loss by Fire, by Amicable Contribution (more commonly known as The Hand in Hand). Like the Hand in Hand it formed as a mutual, in which policyholders shared the risks.

At the formation of the Philadelphia Contributionship, policyholders were given a seven year renewable term and would pay a deposit, refundable at the end of the seven years, minus a small fee for the survey, policy and fire mark. Surveyors were sent out to inspect buildings before insurance was agreed. The directors would review the surveyor’s reports and set the rate.

The contributionship’s first fire marks consisted of four clasped hands, and were originally brightly painted – so similar in design to that used to represent the Hand in Hand and The Union.

The Philadelphia Contributionship for the ‘Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire’ was often referred to as the Hand in Hand, it is the oldest insurance company in America and is still operatiional today.

Return to start

The Philadelphia Contributionship for the Insurance of Houses from Loss by Fire issued this fire mark for policy number 205 to Jonathan Zane of 46 Almond Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania around 1753

Visit next gallery

Fire! Risk & Revelations

Gallery 3: Powered by the Industrial Revolution

Expansion and growth in the industrial revolution

(1760 – 1824)

Evolution of fire insurance, the fire offices and their firefighting brigades

Return to:

Gallery 1: Rising from the ashes

The birth of fire insurance

(1666-1696)

Support IM, Become an IM founding member, visit: www.insurance.museum/membership

To receive latest news and updates on the Insurance Museum’s progress and activities, sign up to the Insurance Museum Newsletter.

Sun Fire Office manual fire engine courtesy of National Emergency Services Museum in Sheffield

Registered Charity address:

C/o Chartered Insurance Institute

3rd Floor, 20 Fenchurch Street,

London EC3M 3BY

Charity No. 1188138

Sign up to Newsletter

© Copyright Insurance Museum 2026