Beta Mode

Manufacturing growth

The first signs of industrial change gathered pace in the mid-18th century. Over the next 150 years, Britain moved out of an agriculturally based economy and into an industrial one. It brought radical change to the livelihoods of the population, created urban centres, stronger trade around the world, and spread the country’s wealth to regions outside of London.

View slides

Why it started in Britain

One reason the Industrial Revolution began in Britain, was the ingenuity of a small number of inventors and scientists. During the 19th century, Britain was known as the “Workshop of the World”. While this was indeed a core reason for the commercial success of Britain, there were many other factors at work.

Read more...

For example, Britain had established international trade connections, had a growing population, easy access to raw materials, capital to invest, plus a large agricultural population ready to supply food for the workers in the factories and cities. On an individual level, success also required business acumen including an understanding of law and a grasp of marketing.

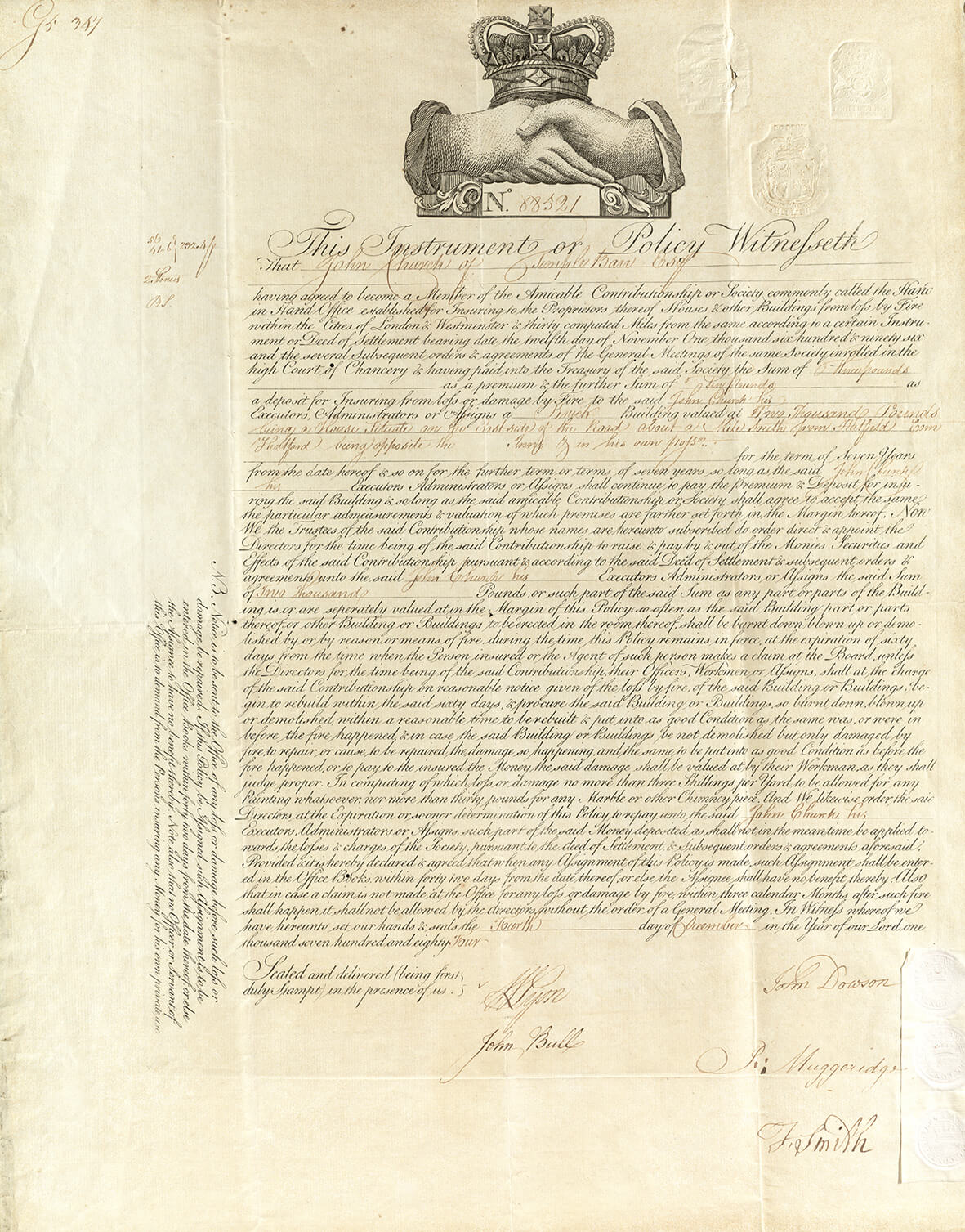

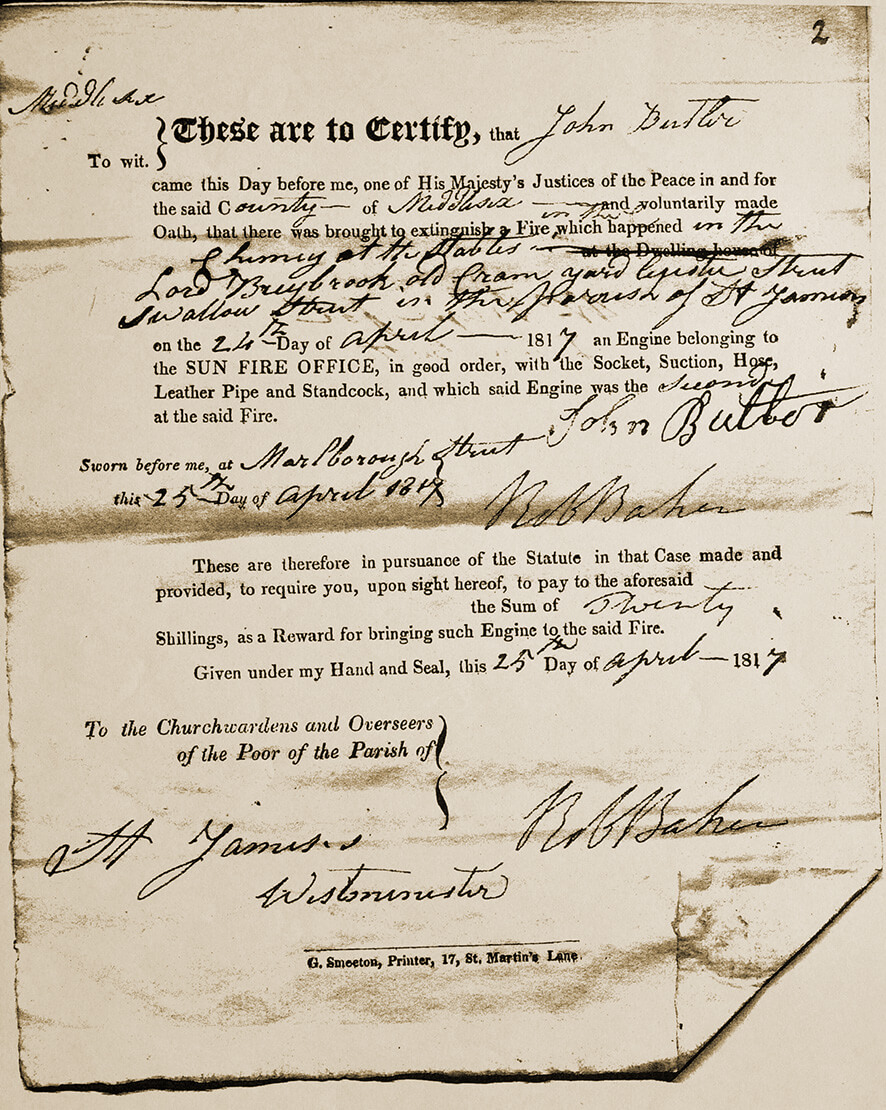

Fire insurance also played its part in Britain’s industrial growth. By providing protection for investment in raw materials, machinery and the buildings that housed them, fire insurance helped mitigate risk.

Cotton ‘spinning mule’, invented by Samuel Crompton in 1779. Combining the spinning jenny and water frame, stronger and finer thread was produced, and revolutionised the textile industry.

Cotton mill expansion

It was the explosive growth of the cotton industry that powered the industrial revolution more than anything else.

Cotton had been the preserve of the wealthy, until technological advances such as the creation of larger spinning mules and water frames, made cotton available to the masses. Demand was huge. At one point there were about 900 mills across Britain – all making vast profits for their wealthy owners and accounting for about 5% of the national income.

Read more...

In Britain, the cotton industry was focussed in the North West of England, particularly Nottingham, Manchester and Lancashire – increasing the wealth of these regions.

Factories offered more money to workers than agriculture did. Up until the 1830s, children were often employed, working long hours and in harsh conditions. Quite often they worked 12 hours a day and six days a week. In return the children were provided with food, shelter and a basic education.

Cotton plant seeds surrounded by fluffy cotton fibers, harvested to produce cotton.

A significant fire risk

Minor fires were a frequent occurrence in cotton mills.

The nature of the materials, process and the heat friction caused by the moving parts of the machines contributed to the risk of fire.

Read more...

Mills destroyed by fire included:

Bate Mill, March 1820: in a little less than an hour, the fire consumed the machinery, the stock, the furniture and dwelling house.

Beard Mill, April 1832: cotton dust took fire when it came into contact with part of a new blowing machine causing heat friction. The mill was not insured.

Schofields Mill, October 1838: the building and machinery were all destroyed. The mill was insured for £4,000 – considerably below the amount of the loss.

Cotton mill fires were frequent (AI generated image).

Innovations in the textile industry

John Kay’s 1733 flying shuttle

John Kay's flying shuttle was a weaving invention that enabled weavers to produce wider cloth more quickly, by allowing them to operate a shuttle with one hand, increasing productivity and efficiency.

Richard Arkwright’s water frame

Richard Arkwright's water frame was an invention in the textile industry that used water power to drive spinning machines, increasing the efficiency and speed of textile production.

James Hargreaves’ spinning jenny

The spinning jenny consisted of a frame with multiple spindles on which to wind thread. The operator used a hand-crank to rotate a wheel that drove a set of connected spindles, which would spin and wind the thread onto the spindles as the operator fed the fibers. This allowed for the simultaneous spinning of multiple threads, significantly increasing productivity.

Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule

The spinning mule combined the features of two earlier inventions - the spinning jenny, which allowed multiple spindles to be operated at once, and the water frame, which used water power to spin the thread. The Spinning Mule was powered by a hand-cranked wheel that rotated the spindles, and the thread was pulled out and wound onto bobbins.

Read more...The Mule's spindle carriage could move back and forth, allowing the spinner to vary the thickness of the yarn produced. This innovation allowed for a much more versatile and flexible production process than earlier spinning machines. The resulting thread was stronger, finer, and more even, making it ideal for producing high-quality cotton fabrics, and it greatly increased the efficiency of the spinning process.

Samuel Crompton couldn't afford to patent his machine, which was widely copied and transformed the cotton industry and the development of modern factory-based manufacturing.

James Watt’s steam machine

James Watt's steam engine was a heat-powered machine that converted steam pressure into mechanical power, used to drive machinery. The invention in 1775 was a significant improvement on earlier steam engines, increasing efficiency and enabling its use in a wide range of industrial applications.

Return to start

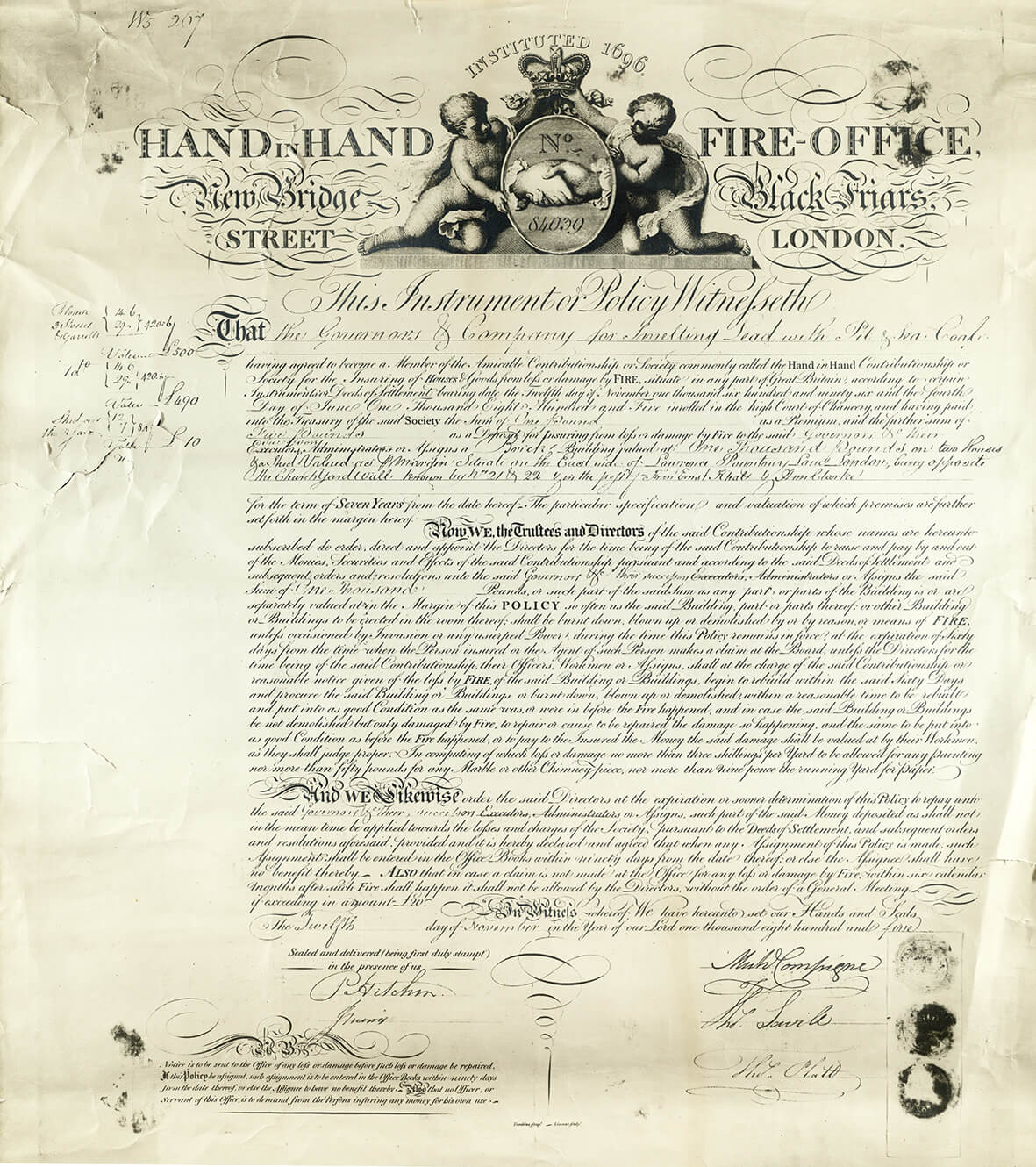

Newfangled fire risks

Industrial growth and the social and economic impact of the changes it brought, led to the emergence of new complex fire hazards. However, by reducing the uncertainty and fear of property loss through fire, fire insurance acted as an incentive for accumulation, investment and innovation during the 17th and 18th centuries.

View slides

The risks

Growth in industry led to many new risks for fire insurance and the development of specialty risk.

Industrial property

Industrial buildings were large in scale and housed expensive machinery and raw materials. Because the fire hazards they brought were new and unexpected, underwriters were unsure how to categorise and rate them.

Fires were particularly hazardous for textile mills. Lint and fabric dust hung heavy in the air, oil saturated wooden floors and grease lubricated the machinery. In addition, flammable raw materials such as stacks of cloth, paper, wood and coal lay all around.

Read more...By far the greatest concern were the premises of sugar bakers. From the later 1730s the Union, Westminster and London Assurance abandoned the sugar industry altogether. The Hand in Hand kept its rates low but suffered repeated fires. Between 1721 and 1738 the office paid claims totalling nearly £5,000 on just four sugar house fires. From 1751 to 1800 the office paid over £14,000 on 22 sugar houses, 17 of which burnt to the ground.

Equipment

The cost of equipment in such industries as glassmaking, brewing, sugar refining, soap boiling, printing and dyeing all added to the capital values that were potentially insurable.

Machinery to consider included silk looms, cutting and polishing machines for mirrors, horse-powered saw mills, and shredding machines for tobacco.

New goods and raw materials

Warehouses and shop storerooms created another complicated market for insurance. London in particular drew in enormous quantities of wool, corn, malt and coal from inland and coastal trades. In addition, tea, coffee, sugar molasses, wine, spices, silk, tobacco, oils, china and timber were all imported from overseas. All these needed to be assessed individually in terms of risk and value.

Multiple occupancy

Because of the lack of available commercial and industrial space in urban areas, sections of warehouses were sometimes converted into reeling, spinning and weaving rooms for subletting. The fact different industries were housed in one building by different tenants, increased the fire hazard and the complexity of risk assessment.

London

The many trades, industries and property types in London, made the task of underwriting in the capital increasingly complex and underwriters were known to discriminate by location, as well as by industry or trade.

Trades associated with the riverside were among the most hazardous in London - sugar bakeries, distilleries, breweries, gunpowder mills, glass-houses, soap and tallow manufacturers.

Read more...Insurers were particularly concerned about the risks associated with a district around London Bridge. Dwellings, workshops and warehouses were thrown up rapidly with little regard to the quality or materials of construction or the goods and manufacturing processes they contained.

The area became notorious to underwriters as the “waterside district”. It had a reputation of being noxious, crowded, drunken and violent. The Hand in Hand established a standing committee in 1762 to consider insurance in this district and following several large fires in 1765, the office suspended insuring houses in any streets within 100 yards of the river on both banks.

New sector risks

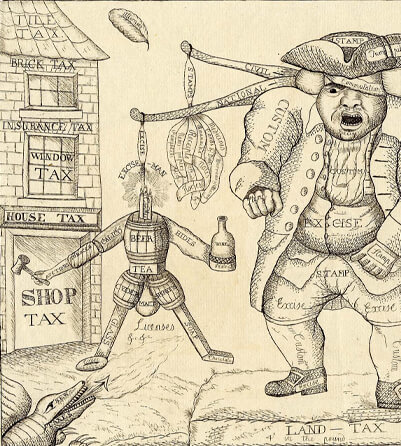

A booming economy introduced new sectors of risk for the fire insurance industry to consider.

Retail

The common retail shop was a general store with a stock of mixed goods where small packets and parcels were stacked high on shelves and laid across counters and floors, adding to fire hazard. Some shops were subdivided between different types of retailer making assessment for insurance purposes even more difficult.

(Image courtesy The British Museum)

Catering

Catering was also another large diverse market for insurers. Inns, taverns, alehouses and coffee houses could prove to be complicated risks.They could provide lodging, stabling, warehousing, coachhouses, ironmongers shops and hosting markets.

Theatres

Theatres and other places of entertainment were attractive to insurers because of their size and value, but they proved hazardous to insure. The cost of rebuilding Haymarket theatre after the fire of 1789 was said to be over £85,000 plus a further £50,000 for its contents (including scenery, wardrobe and other contents). Covent Garden theatre cost over £300,000 after the fire of 1808.

Insurance expert

Learn more about the impact on insurance of the changing social, economic and technological advances of the day with Insurance expert Robin Pearson.

Newfangled risks - some of the challenges insurance companies had to face with unknown categories and types of risks.

How insurance companies dealt with assessing new risk.

Co-operation in the 1790s

Arson

Not everyone was happy with the changes brought in by the Industrial Revolution and arson through protest or fraud became an additional challenge for the fire offices.

Protest

The Luddites were a secret group of English textile workers who formed a radical faction which destroyed textile machinery. Luddites feared that machinery would replace their role in the industry. Many Luddites were owners of workshops which closed because factories could sell similar products for less.

The Luddite movement began in Nottingham but spread across the country in 1811-1816. Handloom weavers were blamed for burning mills and pieces of factory machinery.

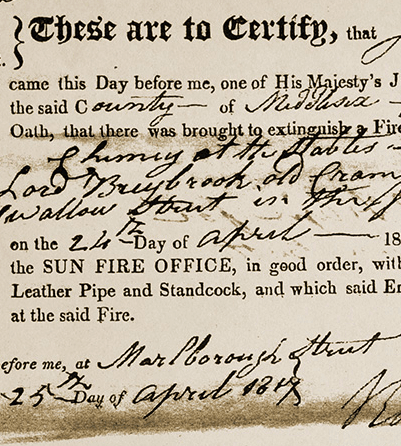

Fraud - Salem Mill 1799 - 1800

A series of fires at Salem Mill raised the suspicions of the Royal Exchange Assurance.

The first, in April 1799, almost destroyed the whole premises. Then in May there appears to have been another fire, as the Royal Exchange Assurance Office offered a reward in the Manchester Mercury for information to convict the persons who had twice tried to burn down the mill.

Read more...In February 1800 the Royal Exchange offered a further reward for the fire raiser’s conviction and the next month a John Matthew Jackson appeared in court charged with wilfully setting fire to the cotton mills.

It seems Jackson may then have implicated mill owner Edward Bower in the scandal, Edward Bower was brought to trial at Derby Assizes accused of setting fire to his own cotton mill. He was convicted and sentenced by the court to pay a fine of £100 and was imprisoned for 12 months - only to be released once the fine was paid.

The prosecution was initiated by the Royal Exchange Assurance Company who had insured the mill machinery and contents for upward of £3,000.

Legal action

In 1765 the six London fire offices shared the costs of prosecuting arsonists at Wapping and Limehouse and in 1779 at the instigation of the Hand in Hand, the fire offices established a joint committee to apply to parliament to tighten the laws against arson.

Insurance expert

The challenge of Arson, with Robin Pearson.

How Arson was used as a method of protest or fraud.

Return to start

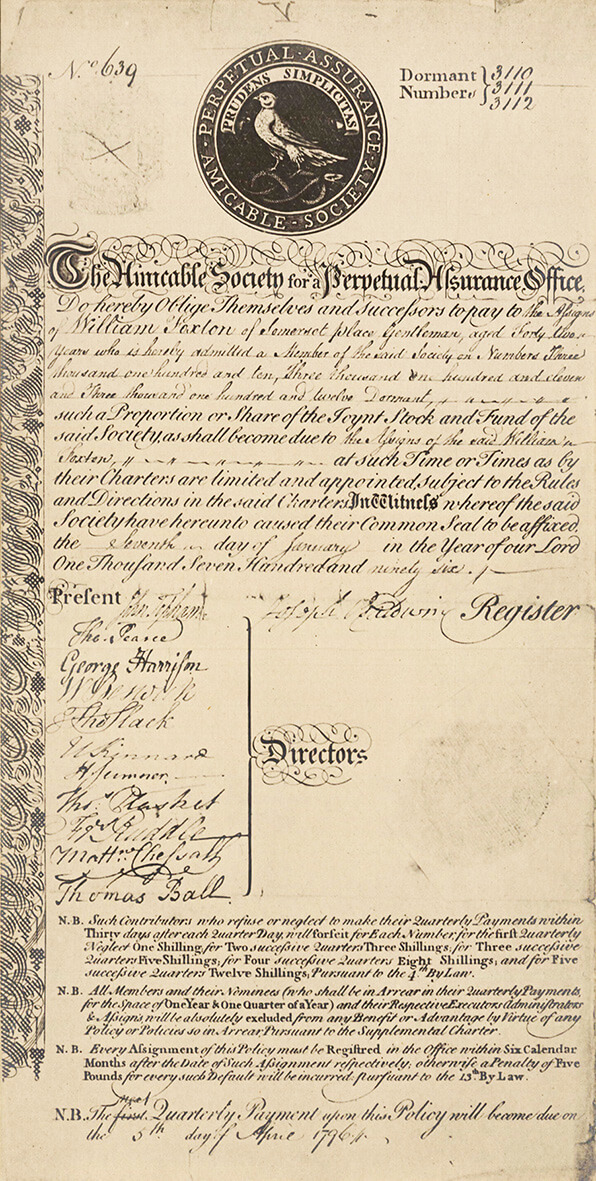

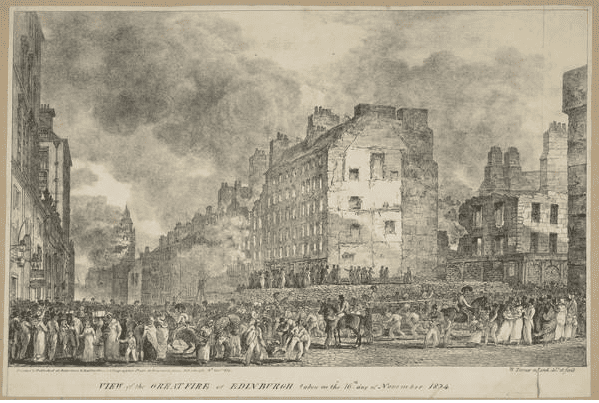

London and beyond

Following the South Sea Bubble Act of 1720, insurance faced a period of stagnation, until the 1760s when there was a period of rapid growth with regional and global expansion.

View slides

Global expansion

In January 1782 a new insurer, The Phoenix Assurance Company opened its doors for business in London, the first new fire office in the capital for 60 years and the first to specialise in insuring large industrial risks.

Read more...

In the second half of the 18th century, fires at sugar refineries accounted for a large proportion of all bankruptcies in England. Only two of the fire insurance companies at the time insured sugar refineries, albeit at inflated rates with meagre policy limits.

The Phoenix was an initiative of a group of London sugar refiners who had become tired of the expense and difficulty in obtaining adequate insurance cover from existing offices. Out of about 100 sugar refiners in the capital 84 subscribed to the new venture.

The early strength of the Phoenix lay in its connections to the sugar industry and in its adventurous approach to marketing. It cut premiums on London dockside insurances, moved swiftly into the markets for mills, distilleries and breweries and acquired the lion’s share of London’s sugar insurances. This powerful new office fuelled the competition which had already begun to emerge with the provincial foundations of the late 1760s and 1770s.

Before 1800 the Phoenix had built three fire engine houses in London, the first in Old Cockspur Street on a site now occupied by Canada House.

The phoenix next used its connections in the sugar trade to establish an international sales force of agents. By the early 1800 it had 42 agents across the world, including in Europe, America and the West Indies.

Robin Pearson discusses the Phoenix.

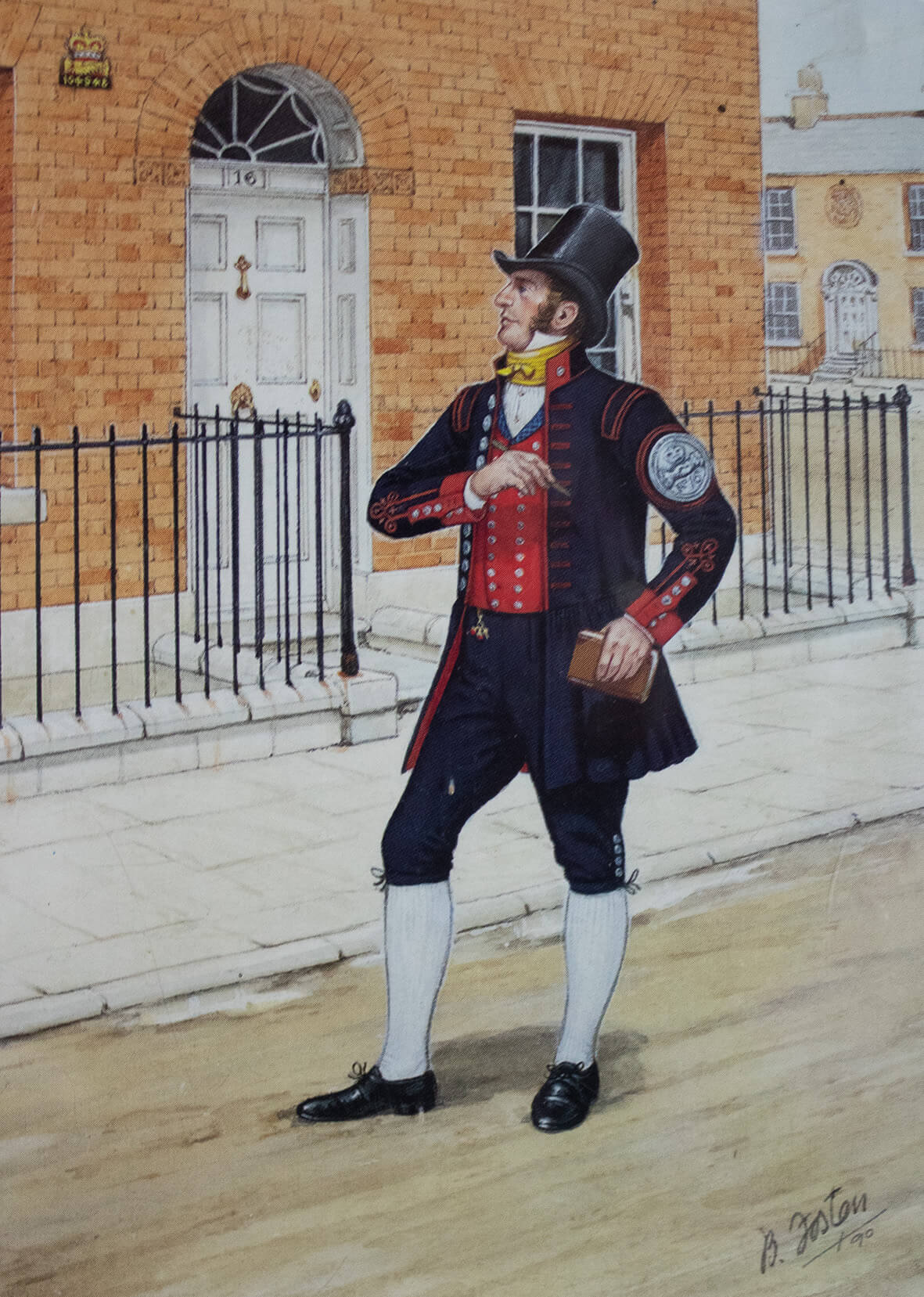

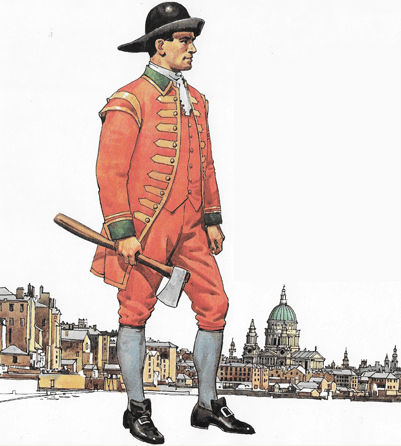

Fireman’s uniform for the Phoenix fire office’s London brigade.

The next generation of insurers

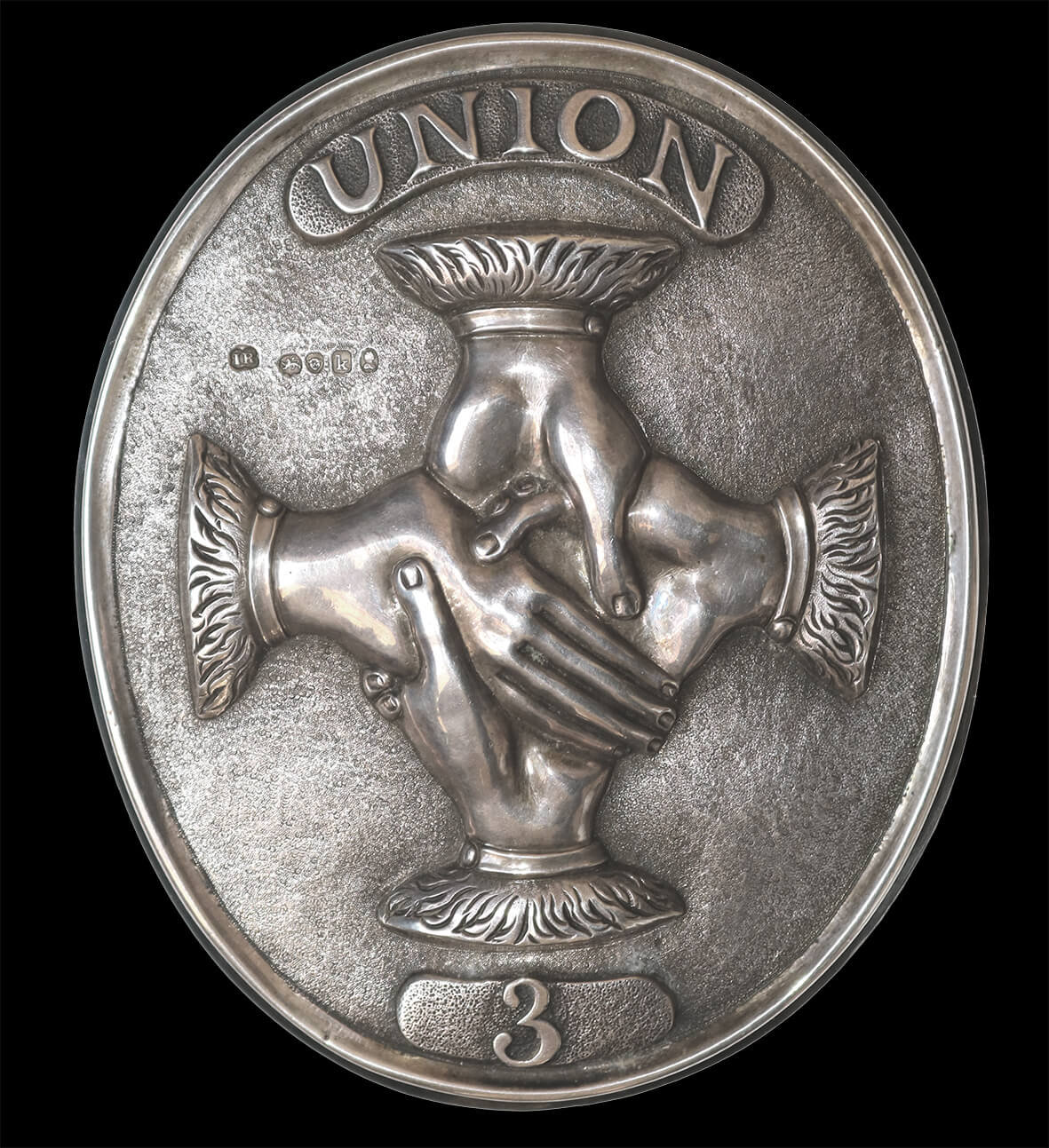

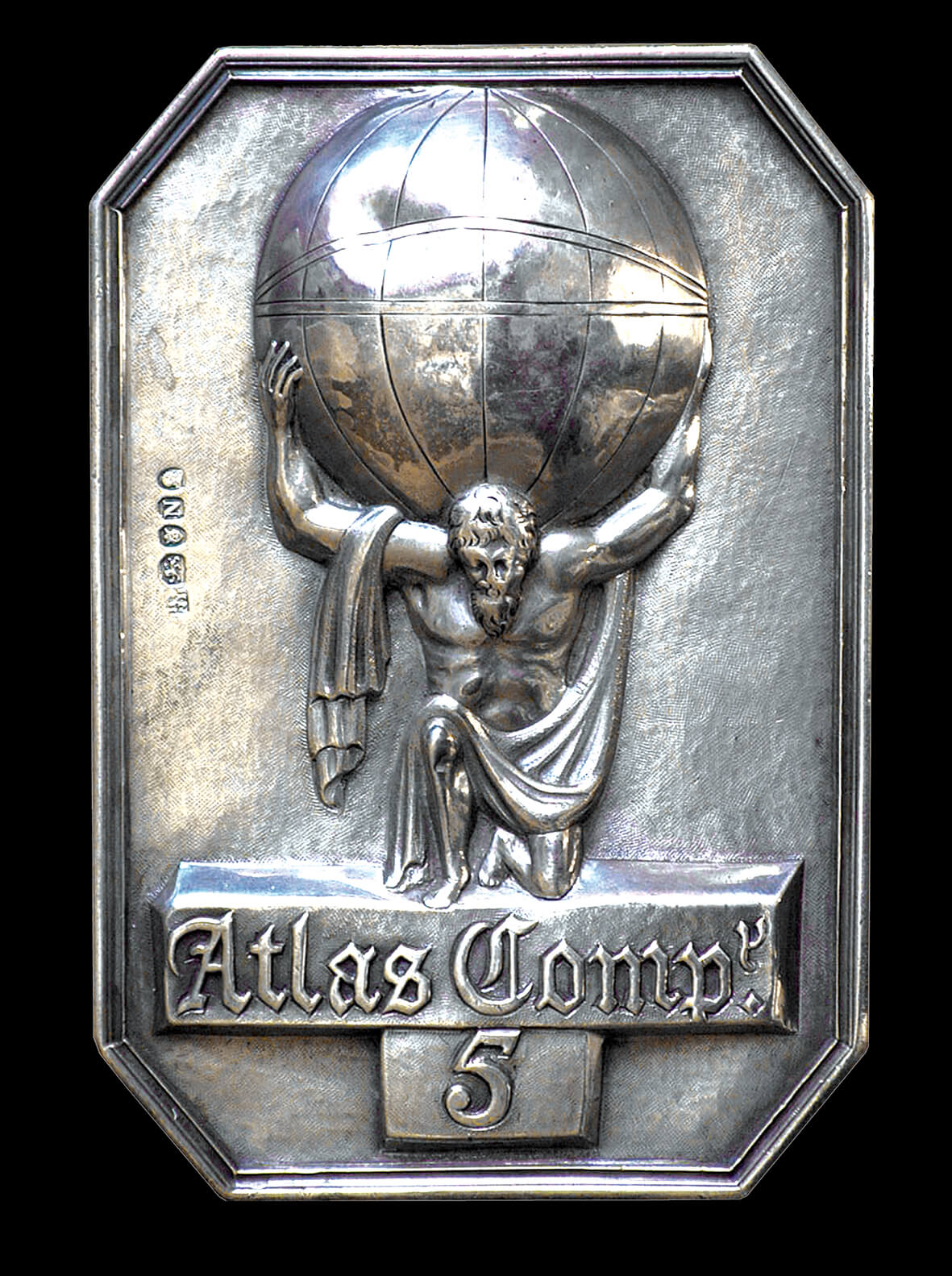

Fire mark examples courtesy of Ron Long's collection

Global ambition

Following in the footsteps of The Phoenix, a series of insurance offices were formed who reflected their global ambitions in the names they took - including the Globe, Imperial and Atlas. each sought a distinctive identity within the industry by establishing strong positions in specialist areas and were among the first to look overseas to grow their business. By the early 1800s these imaginative and ambitious British insurance companies were insuring risks across the British Empire, Europe and America.

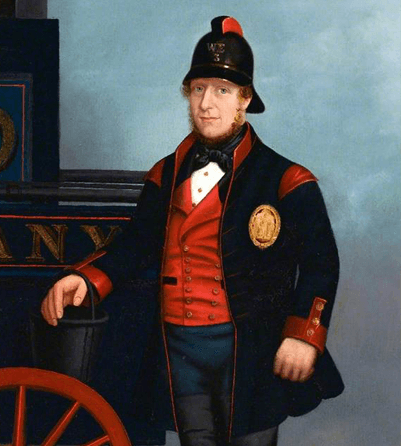

Image of the Phoenix firefighters rushing to a fire.

Read more...These companies were formed via private capital, usually from local manufacturers and merchants. They used existing trading connections and a network of agents to develop their business overseas and from the 1820s they extended their business into co-insurance and early forms of reinsurance.

The success of British insurance companies in overseas markets reflected the expertise they brought with them from decades of experience.

This was particularly shown when gathering claims and data statistics for large industrial warehouses, buildings and machinery. British underwriters became international leaders in risk assessment and risk classification and their methods were often replicated.

From the 1870s through to the First World War, British insurers continued to expand overseas, acquiring foreign insurance companies as well as UK companies with overseas operations.

The Imperial Fire Insurance Company 1803–1902

The Imperial found its competitive edge by offering lower rates and was ruthless in removing agents who failed to generate policies during the first two years of office.

The emblem of a heraldic crown is based on St Edward's Crown made for the coronation of Charles II in 1662.

The Globe 1803–1864

By 1820 the Globe was among the top six fire insurance companies in terms of total sums insured. The company maintained brigades in various parts of the country and continued to underwrite insurance until 1864 when it amalgamated with the Liverpool and London Fire and Life Insurance Company.

The emblem of a globe represented the company’s aspirations for worldwide business.

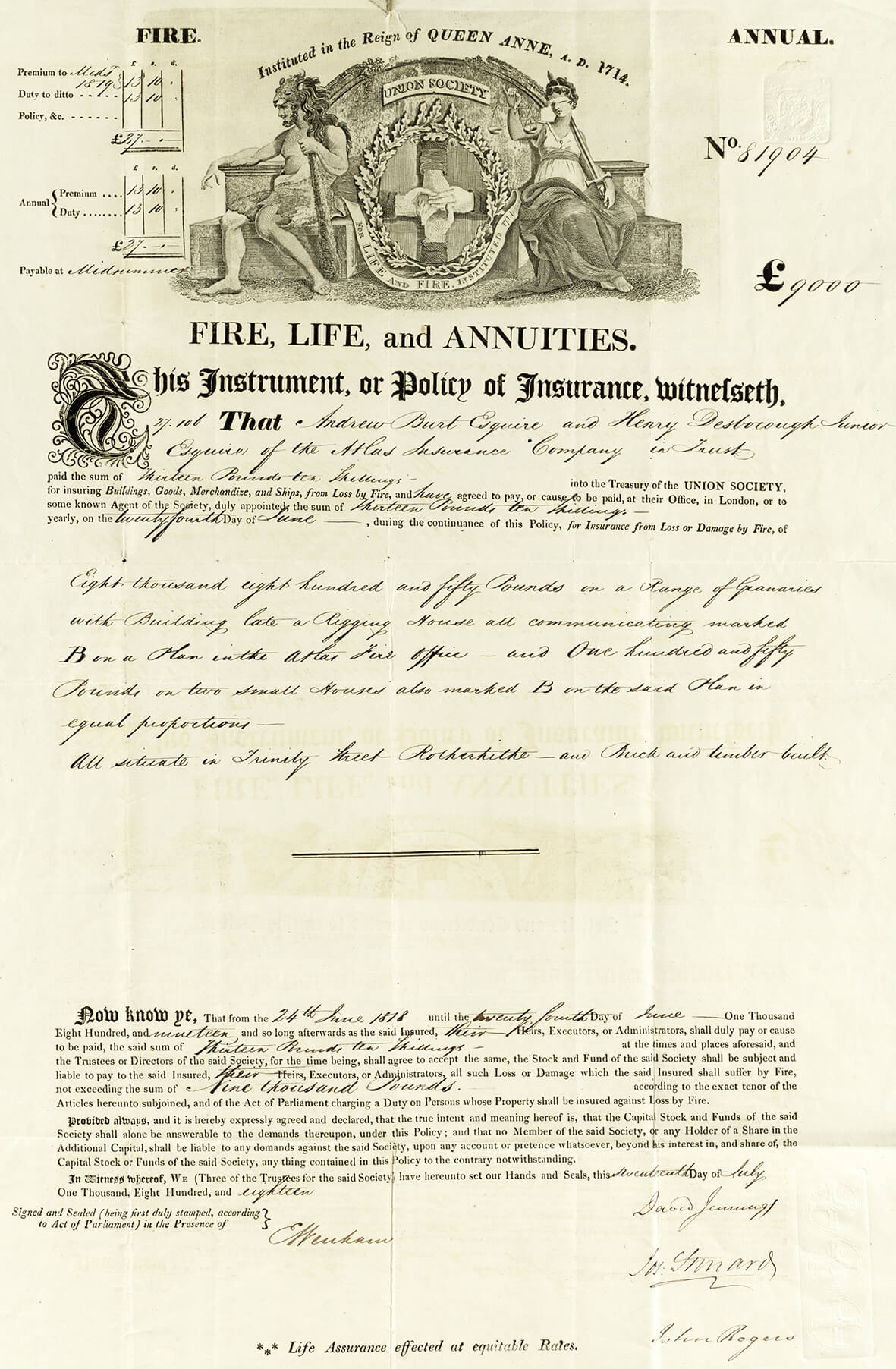

The Atlas Assurance Company, London 1808–1959

In the week before Christmas 1807, six businessmen met in Will's coffee house in Cornhill to found an office for fire and life assurance. They called their enterprise the Atlas to reflect their global ambition.

Read more...114 agencies were established within the first year. Through expanding its sales network and generous levels of commission the Atlas’ country business grew more rapidly than its metropolitan insurances. Agents accounted for 45% of sums insured by 1813-1816 and sums insured rose to £9m. Their main focus was on cotton mills, by 1811 it had earned over £9,000 on cotton mills but paid out only £92 in claims.

From the mid 1880s the company enjoyed a rapid expansion in overseas business. And in 1959 was acquired by the Royal Exchange Assurance.

Its emblem shows Atlas, a mythological figure symbolising strength.

London insurance fire offices 1760 - 1823

Words courtesy of Brian Wright, images courtesy of the Chartered Insurance Institute

London fire offices

In the 18th century, London was the biggest market for property insurance in the world, and the majority of the larger fire offices remained based there. The capital’s fire offices accounted for over 90% of sums insured against fire in Britain in 1730, just over 79 percent by 1750 and 55% by the end of the century. The larger offices developed a network of agents to grow their business out into the regions and later in the century, overseas.

Most London fire offices maintained their own fire brigade of between 24 and 50 firemen (watermen) and auxiliaries.

Image of The Bank of England in the City of London.

The Phoenix Assurance Company 1782–

Emblem: A phoenix rising from the flames, used from the medieval period to symbolise resurrection.

The Phoenix was set up by a group of London sugar bakers. Sugar baking was a particularly hazardous trade and so insurance was expensive. Plus the two main existing insuring companies - the Sun Fire Office and the Royal Exchange Assurance - had a limit of £5,000 insured on any one risk, despite the fact that the buildings often cost up to £10,000 and contained fixtures and stock-in-trade worth between £5,000 and £20,000.

Read more...The company formed a fire brigade in May 1783 in London; it later had brigades stationed at other centres in Britain and provided equipment and engines to local volunteer brigades.

By the end of 1782 six agencies had been appointed and by January 1783 another fifty-two more were added, mainly in important provincial centres.

The agency network continued to expand and agents were appointed overseas - in France and Germany in 1786, in Portugal in 1787, and in many other places for the next thirty years or so. An agent was appointed in New York in 1804, followed by several other agents in eight out of thirteen of the states of the Union.

A large amount of business was conducted in the United States and the Phoenix presented a fire engine to Savannah, Georgia, in 1799 and Charleston, South Carolina, in 1802.

The Globe 1803–1864

Emblem: A globe, an easily recognised symbol and representative of the company's aspirations for worldwide business.

The Globe started as a proprietary company for fire and life insurance under a deed of co-partnership with a capital of £1 million. Its chief office was at 1 Cornhill with a West End branch at Charing Cross.

Read more...In 1808 Sir Frederick Morton Eden of the Globe proposed that the London fire insurance brigades should form a single engine establishment. Only the Atlas Assurance showed any interest and the idea was abandoned until 1833, when an amalgamated brigade was formed known as the London Fire Engine Establishment.

By 1820 duty returns show the Globe to have been among the top six fire insurance companies in terms of total sums insured. The company maintained brigades in various parts of the country and continued to underwrite insurance until 1864, when it amalgamated with the Liverpool and London Fire and Life Insurance Company. The combined companies adopted the title Liverpool and London and Globe Insurance Company.

The Imperial Fire Insurance Company, 1803–1902

Emblem: An heraldic crown based on St Edward's Crown made for the coronation of Charles II in 1662.

The company had its first offices at Sun Court, Cornhill, and 16 Pall Mall, London.

Read more...Buildings and goods on the banks of the Thames between the Tower of London and Limehouse on both sides of the river, were charged a small additional premium owing to the greater hazards present in those areas.

The Imperial maintained brigades in many towns and cities throughout the United Kingdom. The regulations of the Imperial brigade at Somerton near Bristol required the fireman in charge of the engine to live over the engine house and to combine his duty with that of a porter at the company's office. By tradition he was an ex-artillery man, selected on account of his experience with horses. Two or three firemen were retained to be on call, the company relying upon members of the public for further assistance in fighting fires.

In 1902 the Alliance Assurance Company negotiated for amalgamation with the Imperial Fire and the Imperial Life.

The Albion Fire and Life Insurance Company 1805–1858

The Albion had a head office at the corner of New Bridge Street and Ludgate Circus and undertook a wide range of insurance in both the UK and overseas.

Read more...A copy of the Albion's proposal dated 25 March 1809 shows that the company did not attach much importance to fire marks, since it states: “it is not the practice of this company to affix marks on buildings. It is known that such marks are used only as a mode of advertisement. They continue on buildings many years after policies have ceased; and afford no guide whatever to the firemen of any company to regulate the attention they might show to persons really insured. The company trusts that its conduct and character are sufficiently popular to remove the necessity of any such species of advertisement; and as the firemen of the company are enjoined to render the utmost assistance to all who need it, the security of persons insured would in no respect be diminished by the disuse of this superfluous appendage.”

Despite its dislike of fire marks, the Albion did issue a few, probably to policyholders who insisted on having one so that they were 'properly insured'. The mark was of a simple design which would have avoided the cost of an artist to design it and also enabled it to be made cheaply of cast iron, using sand moulds, by an ironfounder.

The company advertised: 'Powerful Engines, of the most approved construction, have been provided to render aid in cases of fire; and a corps of Firemen of great strength and activity has been appointed, and is maintained at a large expense, to add still further to the public security. The men are distinguished by a uniform of dark green with scarlet facings; and by a silver badge, bearing a figure of St George overcoming the Dragon, as the emblem of the Company.'

In 1828 the fire business passed to the Protector Fire Insurance Company, but the Albion continued its life business until 1858, when it passed to the Eagle Fire and Life Insurance Company.

The County Fire Office, London 1807–1906

Emblem: It is said to be Britannia. However, earlier depictions of the female figure closely resemble the goddess Athene, a protective deity, and only later does she become recognisable as Britannia. The lion symbolises strength and security.

The founder of the company was John Thomas Barber Beaumont, a well-known painter of miniatures and pamphleteer.

Read more...It was established as 'an association of noblemen and gentlemen' with a subscribed capital of £300,000. This was one of the first London-based companies to underwrite country risks such as farm stock and hayricks. It had what at the time was a new method of attracting business, since it refunded a sum equal to 25 per cent of all premiums paid to every person who continued his insurance for seven years. This scheme was an innovation in fire insurance, and, being linked to a careful selection of risks, ensured the success of the project.

One of the first claims during the early years was from the Duke of Rutland. Fire broke out in 1816 at Belvoir Castle and caused £120,000 of damage. The whole ancient structure was reduced to ruins, and the board and the Duke were convinced that the fire was deliberate but were unable to prove it. Unfortunately the insured value was for less than the assessment of the damage caused.

The County's London brigade consisted of a foreman, deputy foreman, engineer, two firemen and five 'super-numeries', all recruited from among the Thames watermen. Until 1817 the engine was situated in the yard of the Old Bell Tavern in the Strand.

Barber Beaumont was well aware of the advertising value of fire marks, as in 1821 he wrote in a letter to a County agent: 'In passing through Halifax last week ... I did not observe any of our marks up ... which I wondered at. Pray employ a man to ... fix them on all buildings insured with us.”

Agrarian unrest between 1820 and 1840 led to many outbreaks of arson. In 1835 losses on farm stock exceeded premium income, and it was not until the 1840s that profits recovered. The company continued to expand until 1906, when the County became allied with the Alliance Assurance Company.

The Eagle Insurance Company, London 1807–1916

Emblem. The eagle is symbolic of strength and protection.

The company was founded in Cole's Coffee House by a group of prominent London citizens. The first office of the company was at the corner of Freeman's Court, Cornhill.

Read more...Of particular note was the additional cover offered by this company on the rent of premises, against their becoming untenable as a direct result of a fire.

The Eagle appointed its first fireman in 1807 and in November ordered two engines from Mr Hadley. However, fire business was not profitable, a fact reflected in the miserable share prices in 1825 of £4,15s on a £50 share. Two years later The Eagle decided to discontinue underwriting fire insurance and transferred its portfolio to the Protector Fire Insurance Company; it was not until about 1915 that the Eagle again opened a fire department.

The life business flourished in spite of this setback, and by 1866 eleven companies had been taken over by the Eagle directly and a further nine as a result of these mergers.

The Hope Fire and Life Assurance Company 1807–1844

Emblem: An anchor representing security.

Founded by a group of businessmen, the company made steady progress, and the duty return for the first quarter of 1821 shows the Hope keeping pace with the more well-established companies from its offices in Cornhill, Ludgate Hill and Oxford Street.

Read more...In spite of what appears to have been a relatively healthy situation, the fire account was wound up in 1826. Life assurance was underwritten until 1844, when the company passed to the Imperial Life Insurance Company.

The Atlas Assurance Company, London 1808–1959

Emblem: Atlas, a mythological figure symbolising strength.

Agencies were established in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Manchester and Ireland and within two years the company was issuing policies on risks in the West Indies.

Read more...One notable feature of the fire policies was a rent clause which for up to six months paid to the claimant a sum equal to any rent that he might be deprived of following the loss of property by fire.

The Atlas firemen, whose engine house was in Earl Street, Blackfriars, relied on public assistance at larger fires, and the company occasionally presented silver medallions to people who gave outstanding help. During an outbreak of arson on Kent farms in 1830 the directors ordered that all farming property insured with the company should have a fire mark, and if any farms had been missed a mark was to be fixed at once. The reason was that property which bore a fire mark was often spared attack by arsonists, who believed that the property owner would benefit from an insurance claim.

The British Commercial Life and Fire Insurance, London 1820–1860

Emblem: The rod with serpents entwined is the cadaceus of Mercury, god of peace and commerce. A later design shows a trading ship with a lion, probably symbolising strength and security, guarding bales and a barrel representing trade.

Read more...This company conducted insurance on lives, sold and purchased annuities and endowed children, as well as having a fire insurance branch.

The company's fire branch returned a government duty of £2,985 in 1824, but during the following year the fire business passed to the Protector Fire Insurance Company. In 1860 the company was amalgamated with the British National Insurance Company.

The Beacon Fire Insurance Company, London 1821–1827

Emblem: Fortuna (Fortune), depicted with the wheel of fortune and a cornucopia (horn of plenty), points upwards indicating an act of God. The cornucopia spills fruit towards the victims of the fire symbolising the benefits gained from insurance.

The company was founded under the auspices of John Clerk, managing director of the European Insurance Company, who became managing director of the Beacon.

Read more...The original prospectus states that besides the advantages offered by other companies the Beacon also offered: “The payment of 5 p.c. on the amount of loss on all property insured with this Company, within one week after the same shall have been destroyed or damaged by fire; and the remainder so soon as the amount of loss can be ascertained. The insurance of rent during the rebuilding of the premises. The insurance of a weekly allowance to tradesmen and others during the period they are deprived by fire of the means of pursuing their usual vocations.'

The company appeared to have a flourishing business, but in 1827 it was found to be in serious financial trouble. The proprietors sustained losses exceeding £40,000, and the unexpired risks were taken over by the Protector Fire Insurance Company. The directors gave Mr Clerk £2,000 to 'go away'.

The Guardian Fire and Life Assurance Company, London 1821–1968

Emblem: Athene, a goddess often associated with insurance, since she was regarded as a protective deity. She was also associated with defensive war, hence her spear and olive branch, and with impregnability since she carried Medusa's head on her shield. She is often depicted with a snake, one of her sacred animals.

Read more...The Guardian was to a large extent a child of the private bankers. Its formation was cloaked in secrecy and the first recorded meeting took place in the City of London Tavern, Bishopsgate, in early November 1821.

In the first year a fire brigade was formed, each of the directors being responsible for suitable nominations. Subsequently the directors became answerable for the silver badges of their nominees, which was just as well judging by a report given in 1830 which stated that 'all were effective except Benjamin Evans, who was an incorrigible drunkard and had pawned his badge'.

Fire business was reasonably successful, although by 1860 the life department had transferred eight times more profit to the profit and loss account than the fire department.

The name of the company was changed in July 1902 to the Guardian Assurance Company Ltd, and in 1968 it merged with the Royal Exchange Assurance.

The British Fire Office, 1799–1843

The company started business on 25 March 1799, insuring property and goods against loss or damage by fire. The head office was at 429 Strand, with a branch office at 21 Cornhill

Provincial insurance fire offices 1760 - 1823

Words courtesy of Brian Wright, images courtesy of the Chartered Insurance Institute

Provincial fire offices

The steady growth in the number of new offices after 1760 took place mostly outside of London and provincial offices remained in the majority from 1780 until the 1840s. Although these offices were relatively small, by 1800 they accounted for 45 percent of all sums insured in Britain.

Read more...There were definite attractions for underwriting outside of London - the country houses and villas were detached and well built and the mansions of the aristocracy became larger and more numerous during the 18th century.

Fire offices based in London often employed agents to cover these areas to compete with the new local fire offices and regional profits could help subsidise the bigger losses from the larger industrial towns and cities.

The wave of new provincial offices included the Norwich Union as well as those founded in Brighton, Maidstone, Ipswich, Colchester, Exeter, Liverpool, Birmingham and Sheffield. Fire offices were also established in Ireland and Scotland. Some provincial offices also had fire brigades, for instance the Kent Fire Office employed at least 63 firemen at one time.

The Bath Fire Office 1767–1827

Fire Mark, based on the arms of Bath. The wall represents the city's Roman remains, the water represents the spa and the sword of St Paul's martyrdom represents the Abbey Church of St Paul.

Read more...Founded by co-partners with a capital of £30,000 in Trim Street, Bath. The annual rates of premium varied between 2s per cent for common and 5s per cent for doubly hazardous insurance, and policyholders could insure for any number of years. After one year a discount of sixpence in the pound per annum was allowed on the premium. The company issued about 460 policies in its first year. Early advertisements state that 'fire bags' were kept at the office in case of need. These were leather bags, bearing the company's emblem, in which goods could be placed for removal to a place of safety in case of fire.

Following a fire at Westgate Buildings, Bath, in 1779, when a great number of goods were stolen, the company decided to form its own fire brigade. By January 1780 its advertisements stated that, 'in the event of fire in any insured building, notice should be given at the office in Trim Street, where engines are always kept ready for use, and firemen will be sent to give immediate assistance, and to take care that furniture, be safely moved'.

By 1792 a total of 5,750 policies had been issued. In 1808 the company's brigade was shared with the Bath Sun Fire Office, 'For the additional security of persons insuring, proper Fire-Engines are provided, and a company of able Firemen are employed in the service of this office, in conjunction with the Bath Sun Fire-Office; which establishment is the only effective one of its kind in the city'. Engines were stationed at six points in the city.

The company never had more than five agents at any one time. The Sun Fire Office purchased the company in March 1827.

The New Bristol Fire Office 1769–1840

Fire mark, based on the arms of Bristol, the design is taken from a fourteenth-century seal. It depicts a ship sailing through a secret port in the tower of the castle, which was there so that large ships could pass out to sea unobserved.

Read more...The first insurance company to adopt 'the liberal plan of paying the whole of the Loss to every sufferer by Fire, without the Deduction of Three Pounds per Cent', as was the usual practice by other companies at the time.

The company rarely advertised in local papers at first, but, when the Bristol Universal Fire Office was formed in 1774 and offered more favourable terms, the New Bristol announced that it had altered its rates of premium for common insurance to match those of the rival company and would in future insure 'Plate, China, Glass, Wainscot of Rooms, and Carved Work'.

Three agents were appointed in 1786 at Trow-bridge, Bath and Wells, and by 1788 an additional eleven agents had been appointed.

Although the company was reluctant to use newspaper advertisements, the increasing competition of London insurance companies with agents in Bristol caused it to reconsider its attitude, and advertisements began to appear in Felix Farley's Bristol Journal.

In 1797 a new set of proposals was issued in which it was stated that the company had established a fund of £240,000 and would be responsible for 'Losses by Fire as far as that sum shall extend but for no more. By 1800 some 11,185 policies had been under-written. The first mention of an Engine House' is in 1810.

In 1840 the directors announced that they had decided to discontinue business and the company had been sold to the Imperial Fire Insurance Company.

The Manchester Fire Office 1771–1788

Fire mark, a lion taken from the crest of the Grelley family, feudal lords of Manchester.

Little is known of this company, but the policy used by the company appears to have been copied from policies used by the Sun Fire Office between 1744 and 1763. The wording is the same except for the name of the office and date of proposals.

The signatures of the Manchester's directors on the policy are witnessed by Thomas Bewley. Bewley worked for the Sun until 1769, and it is probable that when he transferred to the Manchester he took some forms with him. In 1788 the company passed to the Phoenix Assurance Company, which wanted to expand its business and sphere of influence in the Manchester area.

The Bristol Universal Fire Office 1774–1778

Fire mark, the title of the company is supported by firemen of the Bristol Universal, one of whom holds an axe and the other a 'preventer'. The latter was a hook on a pole used to pull down burning thatch - or, in a larger version, walls - to create firebreaks where necessary.

Read more...The company was established for the insuring of 'houses, warehouses and other buildings, household furniture, implements of trade, goods, wares and merchandise from loss or damage by fire'. Their office opened in the Bristol Exchange. The first advertisement of the company, published in Felix Farley's Bristol Journal on 3 September 1774, stated that, ‘The great advantage the public as well as individuals receive by securing property, from loss by fire, is universally allowed, yet many complain of being prevented from taking the benefit of so prudent a measure by the restrictive clauses in all the proposals of their kind that have as yet been offered them - to obviate which the proprietors of this undertaking have determined to pay for plate, china, wainscot of rooms, carved work, etc., according to its value and to insure all large sums on common insurance at the same price as small ones… after the rate of two shillings for every hundred pounds per annum. As an inducement for the public to adopt this beneficial institution the Society have established a fund of fifty thousand pounds to make good any losses that may happen to any property insured by them.'

After four years the proprietors realised that continuing to run the company on only a small premium income was uneconomic, and, as they also had stiff competition from the Bristol Crown Fire Office and the Sun Fire Office, they decided to wind up the company in 1778.

The Bath Sun Fire Office 1776–1838

Fire mark, based on the arms of Bath. The wall represents the city's Roman remains, the water represents the spa and the sword of St Paul's martyrdom represents the Abbey Church of St Paul. The sun in splendour differentiates the mark from that of the Bath Fire Office.

Read more...Established by sixty co-patrons with a capital of £30,000 to insure houses and goods from loss by fire. Initially nine agents were appointed, by 1835 the number had increased to twenty-five. The company did not maintain its own brigade for the first thirty years but relied on the engines of other companies, to which it paid a reward for attendance at a fire. The first engine on the scene received one guinea, the second half a guinea and all subsequent ones 5s.

In 1808 the Bath Sun signed an agreement with the Bath Fire Office to maintain a combined brigade with engines stationed in six engine houses in the city. The combined fire brigade lasted until March 1827, when the Bath Fire Office ceased to underwrite insurance and the business was purchased by the Sun Fire Office. The Bath Sun took over the brigade, or at least part of it, and ran it alone.

The last policy issued by the Bath Sun was number 11,528 and the business was sold to the Sun Fire Office.

The Liverpool Fire Office 1776–1794

Fire mark, taken from the arms of Liverpool, a cormorant with a branch laver, an edible seaweed in its beak (liver bird).

Established to insure buildings, goods and merchandise throughout Great Britain from loss by fire.

The company maintained a fire brigade equipped with engines, but fire-fighting in Liverpool was difficult. Despite its importance as a port, there was no public water supply until 1801. Water came from private wells and was sold from watercarts. A reward of half a guinea went to the first watercart at the scene of a fire.

In December 1794 the directors of the Liverpool decided to discontinue business and transferred their outstanding risks and property to the Phoenix Assurance Company.

The agency used the title Liverpool Phoenix Fire Office for a few years before dropping the word 'Liverpool' from the name.

The Leeds Fire Office 1777–1782

Fire mark, based on the arms of Leeds. The fleece, shown heraldically as a ram suspended, represents the woollen industry which was of great importance to Yorkshire from the medieval period. The three stars or mullets are from the arms of Thomas Danby, who was Mayor of Leeds in 1661.

Read more...The formation of this company resulted mainly from the efforts of a Leeds banking firm, Messrs Beckett & Co. of the Old Bank, Park Row, Leeds. The proprietors clearly had high hopes for their new company as evidenced by the following extract from an advertisement in the Leeds Mercury of 2 December 1777:

For the accommodation of the Public, the Proprietors have provided a New Fire Engine, a sufficient number of leather buckets etc., which will be kept, with those belonging to the town, at the Engine House, Kirkgate, and in case of accident, upon notice given either to Mr William Lidley in Kirkgate or at the above office, the engines may be immediately had.'

Just five years later, 'due to the levying of a Duty on Fire Insurances', the business was transferred to the Sun Fire Office, which offered to take over all existing insurances by the issue of a free policy. The duty referred to was a tax of 1s 6d per cent on the sum insured, levied by the government to raise money to finance the war against the newly formed 'United Colonies of America' which was later known as the American War of Independence.

The Salop Fire Office 1780–1890

Fire mark, based on the arms of Shrewsbury. The leopard's heads appeared on a thirteenth-century seal of the town. They are known locally as loggerheads and are believed to have been derived either from the royal arms of England or from the arms of a local family.

Read more...The Salop's first advertisement mentions the employment of a number of men to assist in extinguishing fires and removing goods. These firemen were supplied with manually pumped fire engines of the Newsham type, buckets, ladders, hooks and other equipment.

Persons who transferred insurance from another company were given free policies; otherwise a charge of 8s 6d was made, which covered the cost of the policy and fire mark over and above the premium.

The company had a lot of local support and enjoyed a privileged position until 1837, when a rival company, the Shropshire and North Wales, was formed. In the original deed of co-partnership it was decided that all profits for the first seven years should go towards a fund for carrying on the concern. The total amount insured on any one risk was not to exceed £2,000 for buildings and £3,000 for stock-in-trade.

The Salop at first operated from the Secretary, Mr Wood's house in High Street, Shrewsbury, but later moved to the Corn Exchange, before moving to premises situated between the Talbot Inn and the Music Hall. There was an adjoining alley which became known as Fire Office Passage since it gave access to Franklin's Livery Stable on Swan Hill where the fire engine was housed.

The office continued to operate successfully for many years until 1889, when negotiations began with the Alliance Assurance Company, which wanted to take over the business. The transfer was completed the following year.

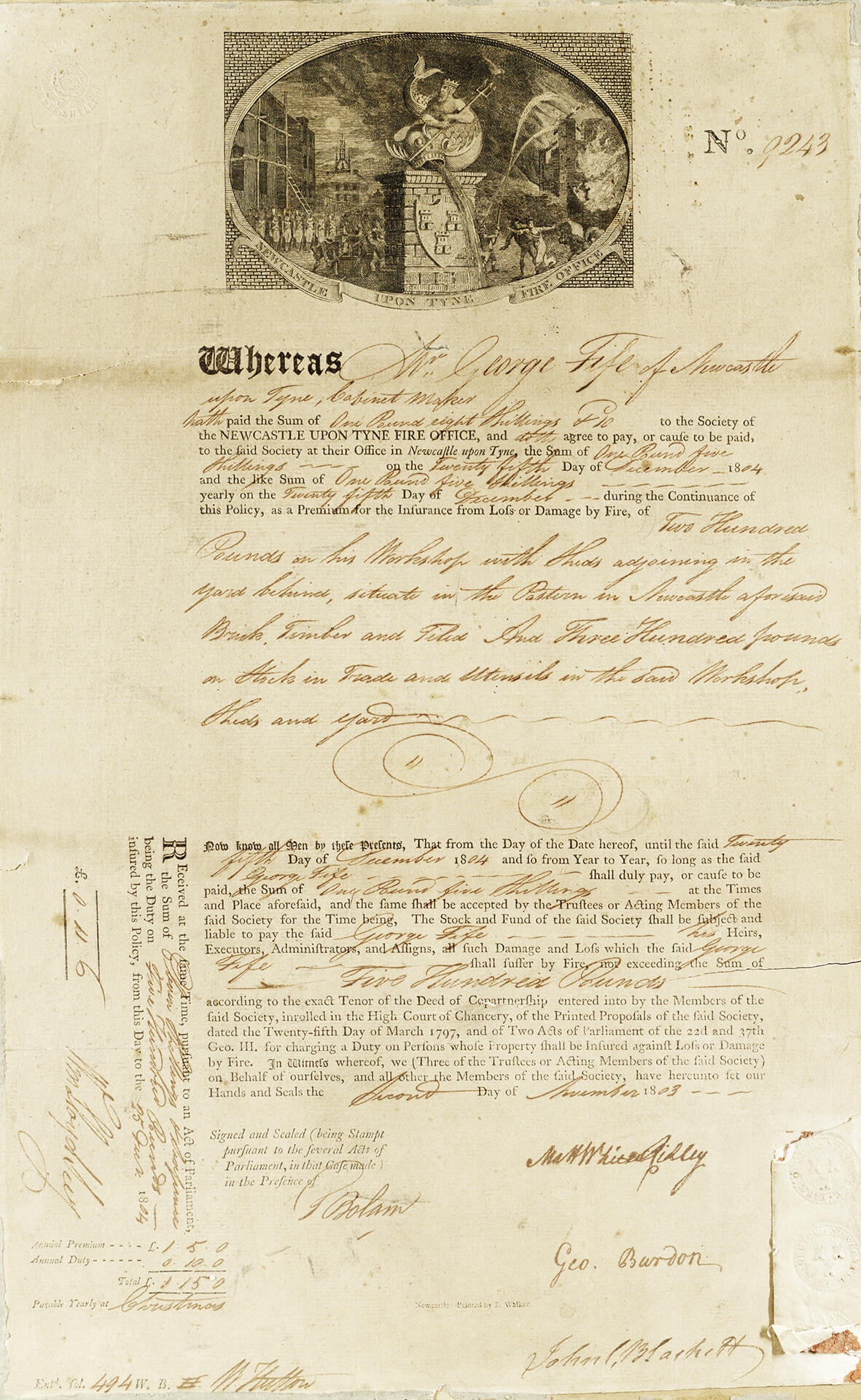

The Newcastle upon Tyne Fire Office 1783–1859

Emblem: Based on the arms of Newcastle, which derived its name from a new castle built by Henry II on the site of an older fortress.

Read more...The Newcastle originally insured widely, but about 1819 it discontinued insurance in Scotland and stopped insurance on cotton and flax mills, concentrating on insurance of private houses, shipping and other non-hazardous risks.

A new set of proposals was adopted in 1820 and farming 'stock and utensils' in all the buildings or in all or any of the yards and places on any one farm, in one sum', were insured at 1s 6d per cent.

The number of proprietors was probably never very large, and by 1831 only twenty-one proprietors accounts are recorded, three of these being represented by executors of deceased members. In 1836 the company wrote to the Sun Fire Office asking if it would like to take over the business, but after due consideration the Sun declined the offer.

The Wiltshire and Western Assurance Society 1790–1835

Emblem: A salamander: a mythical lizard-like creature which could not only live in fire but extinguish the flames.

The society was established on 5 July 1790 with offices at Bradford-on-Avon, Trowbridge and Warminster in Wiltshire and Frome in Somerset, to insure houses, buildings, goods and merchandise from loss or damage by fire.

Read more...In 1792 an advertisement published in the Bath Chronicle the society mentioned that besides houses and other buildings they were now insuring household goods, furniture, printed books, wearing apparel, wares, merchandise, utensils, and stock in trade, and would also effect insurance on farming stock, thatched barns, stables, granaries and outhouses, provided they had no chimney or kiln.

In 1835 the proprietors decided to discontinue the fire insurance business and began negotiations with the Sun Fire Office which resulted in a transfer of the business on 3 November 1835 for the sum of £2,000.

The Worcester Fire Office 1790–1818

Emblem: It depicts Worcester Castle, now totally destroyed and three pears which commemorate a visit made to Worcester by Queen Elizabeth I.

Read more...The company was established in 1790 with an office at The Cross, Worcester, to effect insurance on houses, buildings, goods, and merchandise against loss or damage by fire.

By 1807 the company had twenty-five agents and by 1814 had twenty-nine. It was prepared to insure farming stock and make good losses caused by lightening; as a further inducement to prospective clients, it made no charge for policies.

The company maintained a fire engine operated by part-time firemen from 1790 until 1814, when a permanent brigade was employed. Their uniform consisted of a helmet, waistcoat, jacket, breeches, stockings and shoes. A badge was worn on the left arm which bore the letters W.FO. They were supplied with a manual fire engine, hooks, ladders, buckets, axes and other fire-fighting equipment.

From 1791 to 1817 losses amounted to 50 per cent of premium income exclusive of expenses. This proved too much for the funds, and so in 1818 the business passed to the Phoenix Assurance Company, which continued to maintain the fire brigade at Worcester until the local authority assumed responsibility for fire-fighting.

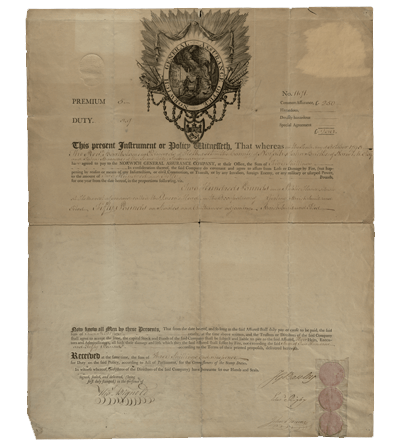

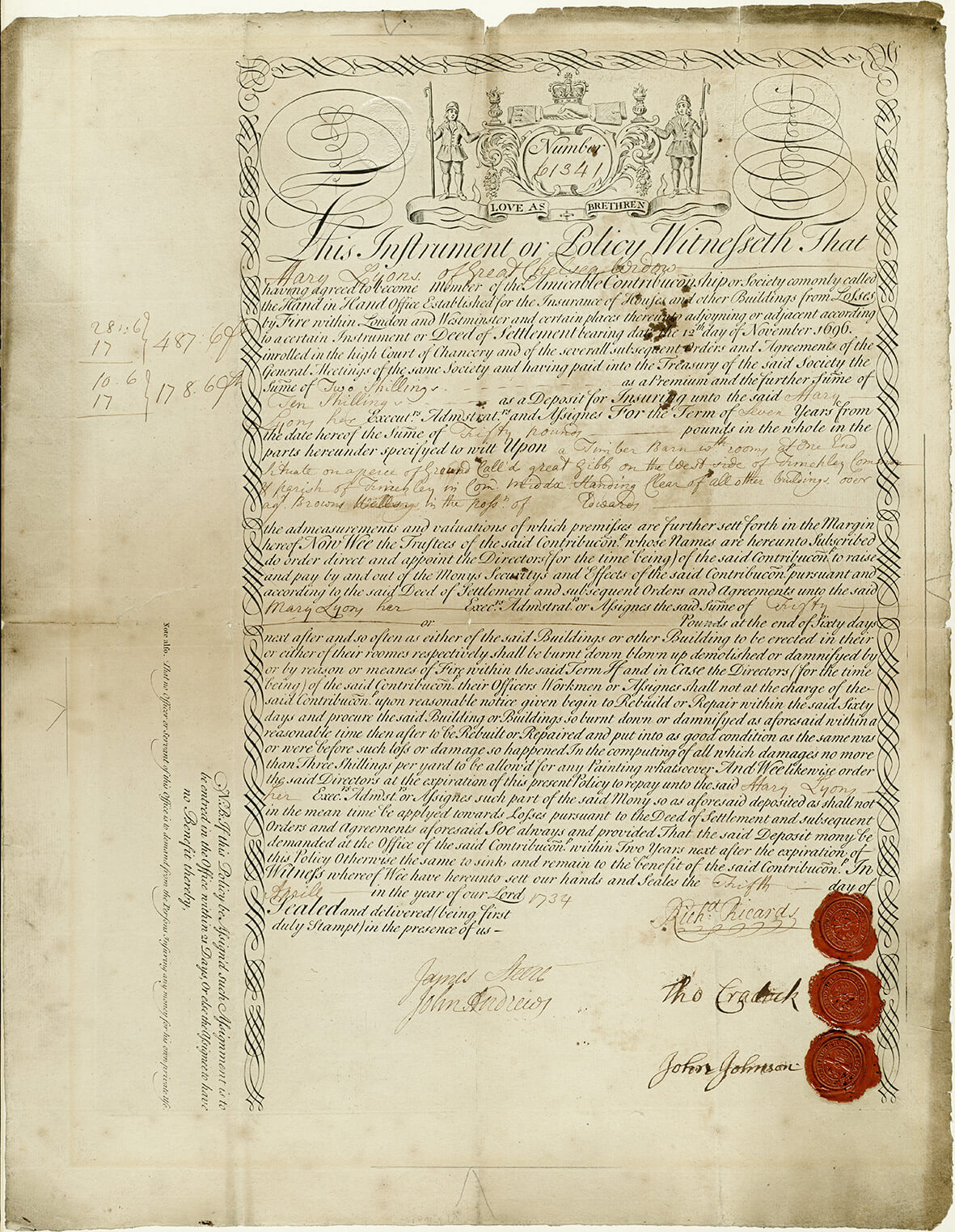

The Norwich General Assurance Company 1792–1821

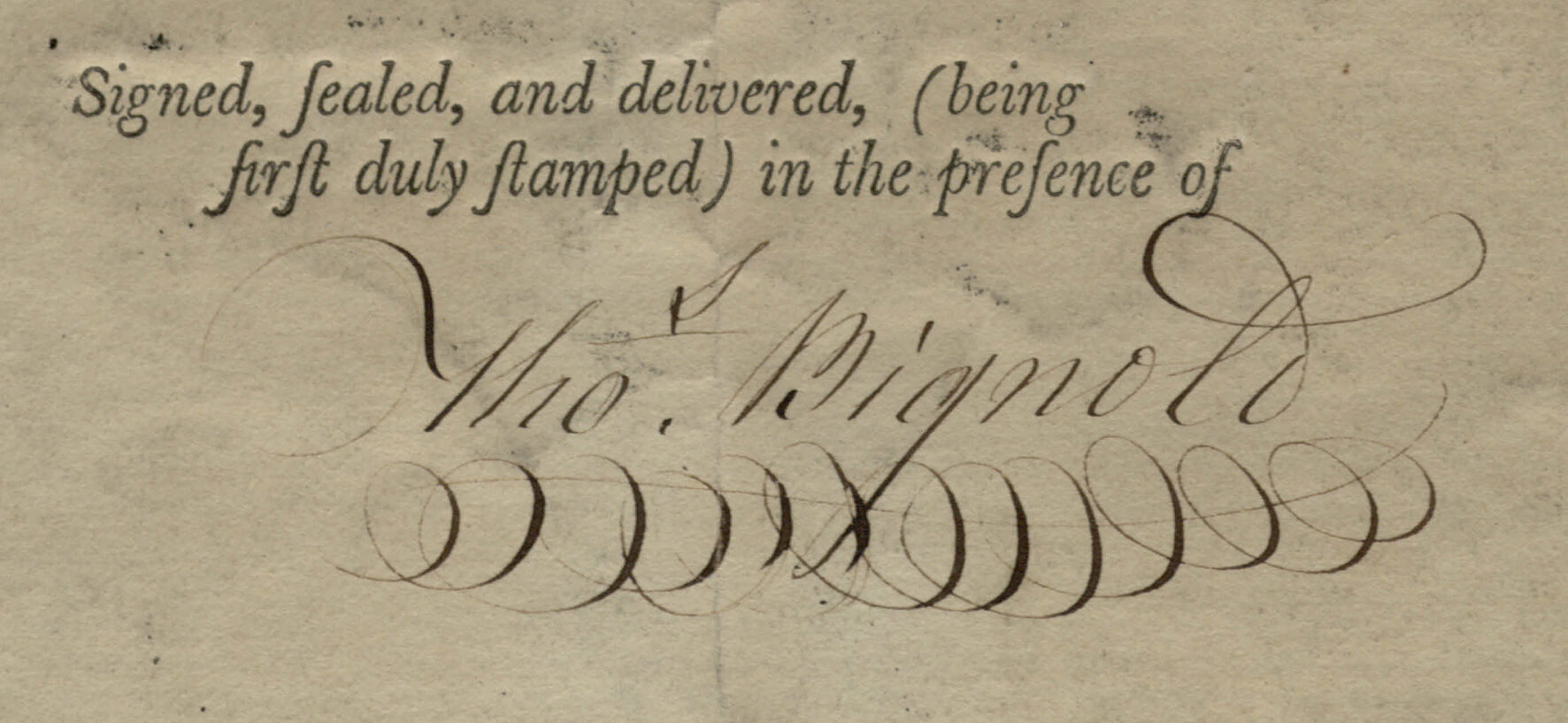

Thomas Bignold with several Norwich citizens first attempted to start an insurance scheme in 1785 to insure houses in Norwich, Norfolk, Suffolk and surrounding areas. It finally opened on Gentleman's Walk in 1792 with Bignold appointed as secretary, although he could only work there part-time, since he also had a banking business and traded as a wine and spirit merchant.

Read more...By 1797 the premium income of the Norwich General amounted to £3,500 for almost £2½ million of property insured. However, Bignold was still thinking about a mutual scheme and in 1797 resigned and started one with no capital and in which all profits, less working expenses, were to be returned to the assured every seven years. This new venture was eventually called the Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society.

Since the Norwich General had been founded for a period of thirty years, the company was due to be dissolved in 1822. However, in 1821 it was decided to amalgamate it with the Norwich Union. This was effected by a new deed of settlement dated 6 August 1821 which raised the capital of the combined company, which kept the name Norwich Union, to £550,000.

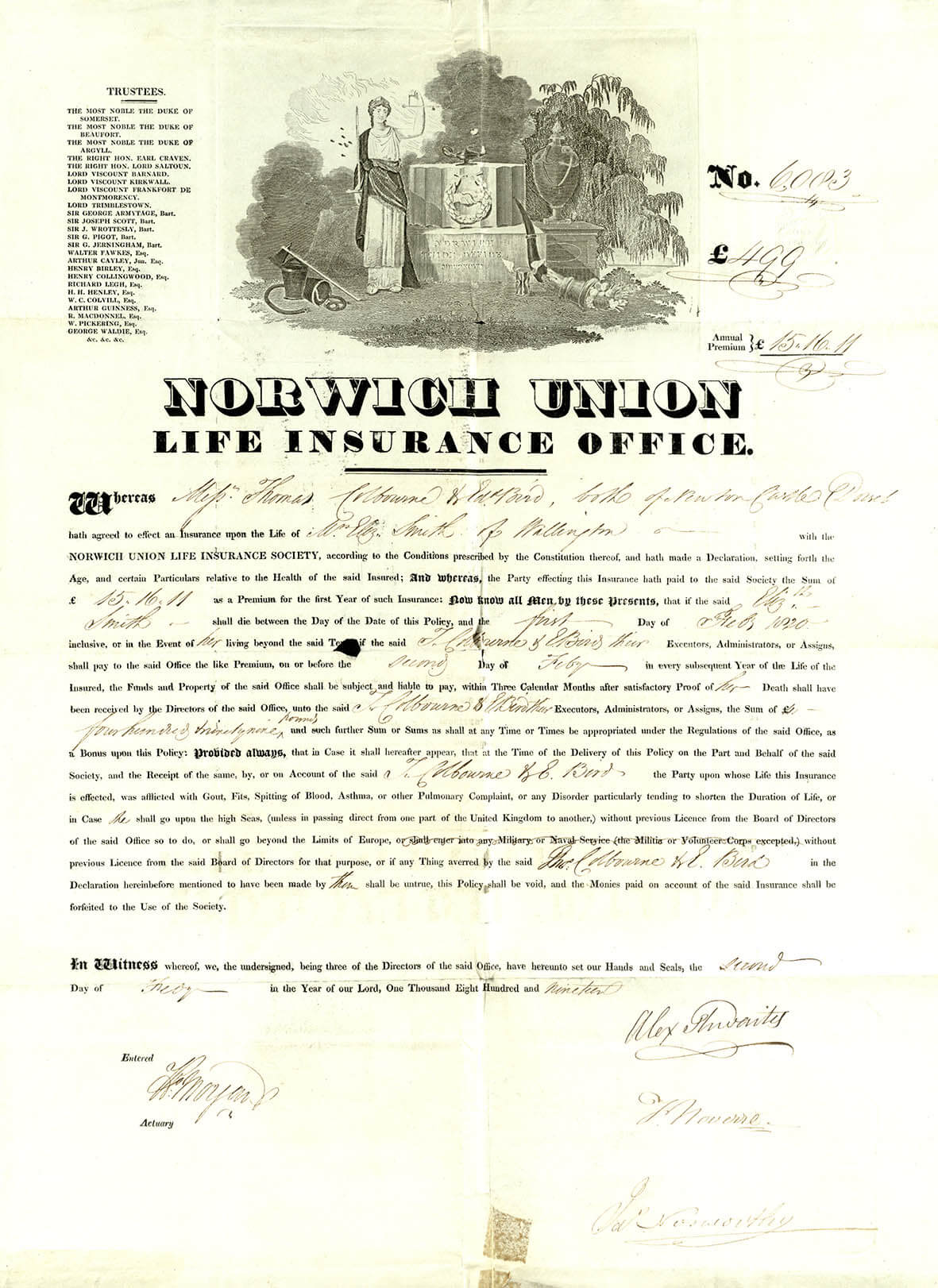

The Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society 1797–

Emblem: Clasped hands and the figure of Justice.

The origin of the society lies with the former secretary of the Norwich General Assurance Company, Thomas Bignold, who had been largely responsible for establishing that company.

Read more...He wished to start a mutual society, which the Norwich General was not, and so left it to form a new society. There were twelve directors, four of whom retired annually.

For the first few years, the growth of the society was steady. By 1804 it had over forty agents in Norfolk and Suffolk. After seven years, it repaid 75 per cent of the premium paid, the amount of insured property and goods having reached more than £3 million. By 1805 it had 6,000 members and almost 120 agents throughout England. The society continued to expand and by 1820 it had nearly 500 agents in all parts of Britain, its premium income was £70,000 and it had returned over £90,000 to its members.

In 1821 the Norwich General amalgamated with the Norwich Union. Following the brief existence of an agency at Bordeaux in 1825, no further overseas agency was established until 1851. The society in 1862 undertook the insurance for the Great Exhibition building. The policy was for £450,000 for one year at 10s 6d per cent, the premium amounting to £2,362 10s and duty to £675. In 1865 the society extended its business to most of the British Empire, China, Japan and most parts of Europe.

The Essex Equitable Insurance Company 1802–1911

Emblem: The arms of Essex. These depict three scramasax, a characteristic Saxon weapon. The scramasax was a single-edged hacking sword, with an angled back, sloping towards the point, represented heraldically as a notched sword. These arms were attributed to the East Saxon Kingdom by the medieval heralds.

Read more...The early part of the nineteenth century was a boom period for the formation of new insurance companies, which by this time were mostly established as joint-stock companies. The mutual system, however, was still occasionally found, the Essex Equitable being a typical example, formed by a group of property owners.

It would appear that the proprietors of the new society were concerned because much of the proceeds of their existing insurance premiums was being used to settle claims in London. They were consequently paying more for their fire insurance than they felt was necessary. No insurances were accepted on properties situated within a ten-mile radius of London, and not unexpectedly therefore much of the portfolio comprised farming stock.

The society prospered, for many years paying an annual bonus in the region of 30 per cent.

The society at first paid for and maintained local parish engines, but this arrangement was unsatisfactory, and engines were purchased for use at Chelmsford in 1803 and Colchester in 1812. Eventually several brigades were operated by the society in the surrounding counties.

The society issued fire marks only in Essex and later in Suffolk, but there was a difference in the method of fixing compared with established London companies. While the latter provided an employee actually to fix the mark to the property, the Essex trusted the insured to do so.

From 1902 the society's reserves failed to keep pace with the growth of premiums and in 1911 the directors decided to allow a takeover by the Atlas Assurance Company, with the condition that the Essex and Suffolk would continue to trade under its own name.

The Kent Insurance Company 1802–1901

Emblem: Based on the arms of Kent, attributed by medieval heralds to Hengst ('the horse'), a Saxon chieftain who invaded Kent. The horse is depicted forcene, i.e. enraged, rearing with both hind hoofs on the ground. The motto Invicta means 'Unconquered'.

Read more...The suggestion that the county of Kent should have its own fire insurance company was first discussed publicly at a meeting in the Bell Inn, Maidstone, on 15 February 1802. One of the founder deputy governors was the former Prime Minister, William Pitt. At first a somewhat parochial attitude towards its area of operation was adopted, and it was not until 1818 that Kent agreed to insure property 'in any part of England'

Their agents were expected to act as firemen if required and so were supplied with buckets. The men were supplied with a board or later a brass plate, to place above the door of their houses inscribed 'Fireman to the Kent Fire Office'. The first manual fire engine was stationed at Maidstone, and by 1811 eleven Kent towns had been supplied with engines.

As an indication of the importance of the use of fire marks for advertising purposes, a statement by a director in March 1804 advised “that were Kent Engine Buckets hung up in the Church at Deptford with a plenty of Marks and handsome Shew Boards put up in Woolwich and Deptford, the whole would greatly contribute to the notoriety, respectability and interest of the Kent Fire Office.”

The Kent was taken over by the Royal Insurance Company in 1901, and as a final gesture it presented the county town of Maidstone with the latest Shand, Mason steam fire engine. Named 'The Queen', the engine continued to be used up to and including the Second World War.

The Suffolk Fire Office 1802–1849

Emblem: Earlier marks showed a star, while on later ones a plough and ram's fleece were used.

The company was officially formed by a deed of co-partnership in 1803, although the business had begun in December 1802.

Read more...The name of the company seems to have been varied quite a lot, the most usual being Suffolk Fire Office, but Robson's Directory for 1839 gives several variations in title: Suffolk and General County Amicable, Suffolk and General Country Amicable, Suffolk Amicable, and Suffolk and General Insurance Company.

Batches of policies were allocated to each division and fire marks were issued by both offices, the letter 'E' or 'W’ being scratched on the back of the marks to denote the issuing office. The office at Ipswich issued far more policies than the Bury St Edmunds one, a total of 1,241 as opposed to 35 in the first year, a trend that appears to have continued throughout the life of the company.

In 1849 the company was absorbed by the Alliance, British and Foreign Fire and Life Insurance Company.

The Hampshire, Sussex and Dorset Fire Office 1803–1864

Emblem: A female figure, probably Vesta, goddess of the hearth, a Roman deity who was prominent in both state and private worship. A temple to her in Rome had a perpetual flame tended by six vestal virgins. She was regarded as the patron of bakers because of the association with hearths and ovens.

Read more...The company was established to transact fire insurance on houses, factories, goods, ships, barges, cargo and farming stock.

The formation and incorporation of the company was opposed by a number of established companies, including the Sun Fire Office, which presented a petition to Parliament.

Little is known of its business history, but it was obviously not very successful, since when it was taken over by the Alliance, British and Foreign Fire and Life Insurance Company in 1864 the annual premium income amounted to just £105.

It transacted fire business only, and it is difficult to imagine why a successful company like the Alliance should bother with such a small acquisition. It is quite possible that the purchase was made purely because, there being a need for the Alliance to expand in this part of the country, it provided a ready-made local office, with suitable employees who were familiar with the area.

The Birmingham Fire Office Company 1805–1867

Emblem: A uniformed fireman standing in front of a large, horse-drawn, manually operated fire engine.

An impressive list of patrons, trustees and directors was drawn from well-known Midlands landowners and businessmen.

Read more...In its first year of business the company seems to have amalgamated with another newly established Birmingham company, the Birmingham Union Fire Office. Also in that year the company built a fire station in Union Street, comprising an engine house, stables and firemen's cottages. It also established local fire brigades, manned by volunteers in Birmingham and the surrounding areas.

Nothing is known of the business history of the company, which passed to the Lancashire Insurance Company in 1867.

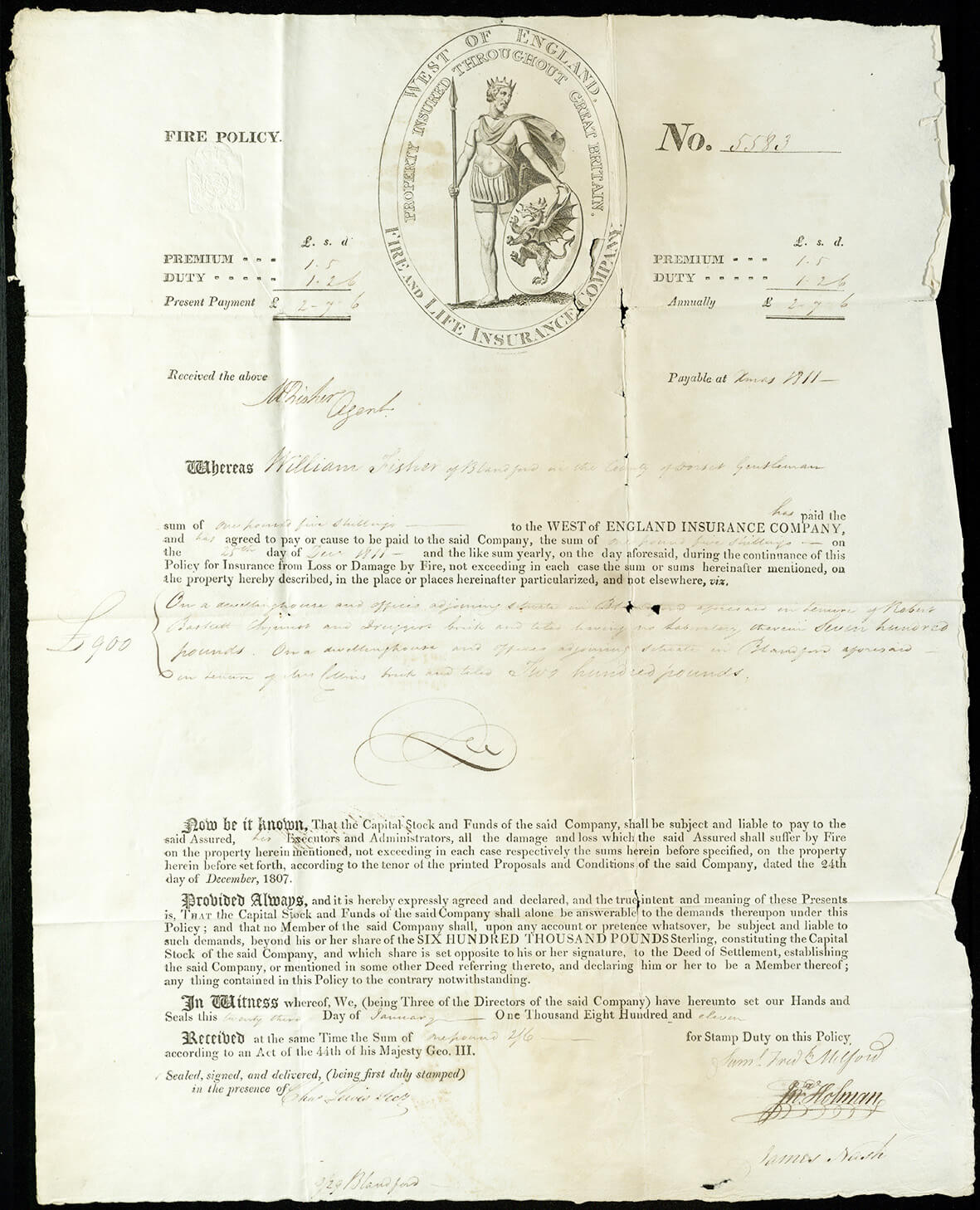

The West of England Fire Insurance Company 1807–1894

Emblem: King Alfred of Wessex, born c. 848, who came to the throne in 871.

The company was established on 24 December 1807 with a capital of £600,000 after a fire which had started in a baker's in Chudleigh (a town near Exeter) had destroyed two-thirds of the houses there.

Read more...A fire brigade was formed in 1808 and consisted of sixteen men with a fire engine and other equipment.

Business rapidly expanded, the company moving to larger premises in High Street, Exeter, in 1820. By 1825 the company was the ninth largest in the United Kingdom, and in 1828 it opened an office and fire brigade at Blackfriars in London. By 1852 the company was the sixth-largest fire insurance company in the United Kingdom.

Early in 1894 negotiations for the sale of the business to the Commercial Union Assurance Company began, and an agreement for the sale was obtained in March 1894. The entire staff of the West of England Company were taken on by the Commercial Union.

The Anchor Fire Office, Norwich 1808–1811

Emblem: An anchor representing security.

The company started business with an imposing array of trustees and directors, one of whom, Jonathan Davey, was an original director of the Norwich Union Fire Insurance Society. The company operated for a short time until it passed to the Norwich General Assurance Office in 1811.

The Sheffield Fire Office 1808–1863

Emblem: Based on the arms of Sheffield. The eight arrows crossed, with a broad arrowhead at each side, represent the cutlery industry for which the town is known.

Read more...The company had the backing of the many local cutlery and allied engineering firms and made good progress, although it did not insure outside Sheffield and the surrounding district.

Before the end of its first year it had moved to larger premises in the Hay Market, with offices on the first floor and manual horse-drawn fire engines housed on the ground floor. The brigade consisted of ten firemen and an engineer under Mr Staniforth, the foreman.

Fire risks in Sheffield were quite high, owing to the large number of industrial premises, and so a part of the local police force was organised into a fire brigade under Superintendent Otter, equipped with a fire engine and escape which were housed at the Town Hall.

In 1863 negotiations were entered into with the Alliance, British and Foreign Fire and Life Insurance Company, which wanted to take over the business. This gave the Alliance valuable connections in Sheffield.

The Bristol Union Fire and Life Insurance Company 1818–1844

Emblem: The faggot may represent fascines - used by the Roman army for filling ditches, etc., which came to symbolise protection and strength in unity, the whole being stronger than the individual.

Read more...A number of former proprietors of the Bristol Crown Fire Office formed the Bristol Union on 5 January 1818. The inhabitants of Bristol were invited to participate in the company, whose capital was intended to be £200,000 divided into 2,000 shares of £100 each but which was increased to £250,000 before the end of the first year.

An advertisement of 28 March 1818 announced that 'A Fire-Engine, on the most efficient and approved principle, with an establishment of active Firemen, will in a short time be ready.’

The proposals issued by the company show that it charged 2s per cent for common insurance, 3s per cent for hazardous and 5s per cent for doubly hazardous, but deductions were allowed for policies over one year.

The company continued to make slow but steady progress until June 1844 when the company's office in Corn Street was purchased by the Imperial Fire Insurance Company.

The Reading Insurance Company 1822–1841

Emblem: It is based on the arms of Reading which appear on a fourteenth-century seal. Edward the Cerding, who reigned 975-78, was assassinated by his jealous stepmother Aefthryth at the age of 16 and is believed to be buried at Wareham or Shaftesbury.

Read more...The company was constituted by a deed dated 25 November 1822 to transact insurance on 'Houses, Buildings, Stock in Trade, Barges and other insurable commodities and effects within the Boro' of Reading'. Every three years the profits and accumulations were divided equally between shareholders and policyholders.

A circular dated 20 July 1841 informed policyholders that the directors had decided to discontinue the business and had instructed the books to be handed over to the Phoenix Assurance Company. The Phoenix guaranteed all existing Reading policies.

There is no evidence that the Reading maintained its own brigade, although the Berkshire and Gloucestershire had a brigade in Reading from about 1824 to 1831 and the Reading may have made a contribution towards this.

Scottish insurance offices 1760 - 1823

Words courtesy of Brian Wright, images courtesy of the Chartered Insurance Institute

The Dundee Assurance Company Against Losses by Fire 1782–1832

Little is known of the business history of the Dundee or its progress.

The company was founded largely as a result of the efforts of David Blair of Cookston, a prominent Dundee merchant who also founded the Infirmary and Lunatic Asylum.

Read more...Blair acted as the company's principal and cashier, the business being conducted from his house in the Murraygate.

The first Dundee Directory, published in 1809, shows the company to have agents in Edinburgh, Perth, Crieff, Dunkeld, Coupar Angus, Cupar, St Andrews, Brechin, Arbroath, Montrose, Forfar and Aberdeen. The Directory also states that 'the Dundee Fire Assurance engine is in the New Inn Entry.

The Aberdeen Fire Assurance Company 1801–1823

Emblem: St Nicholas, patron saint of fishermen, holds a shield bearing the arms of Aberdeen, which, being a fishing port, has its main parish church dedicated to him. The arms of the city appear on seals of 1430, and the three triple towers refer to the three fortified hills on which the city had its origins. The motto, Bon Accord, may have been granted by King Robert the Bruce.

Read more...The company was formed by a number of leading Aberdeen citizens, solicitors and merchants who realised that a fire insurance company would provide protection 'against the heavy individual losses caused by this scourge'.

Nothing is known of the progress or business history of the company, which is believed not to have insured outside the environs of Aberdeen. It was wound up in 1823.

The Glasgow Insurance Company 1801–1841

Emblem: Based on the arms of Glasgow, depicted on town seals of the thirteenth century. The symbols represent the miracles of St Kentigern, the patron saint of Glasgow and its first bishop, who died there in 612. The tree, traditionally a hazel, recalls how St Kentigern produced fire from a hazel branch, the bird recalls the robin he restored to life, and the salmon with a ring in its mouth recalls his intervention to help the Celtic Queen of Cadzow, who was suspected of unfaithfulness by her husband. The bell is St Kentigern's holy bell, a much venerated object.

Read more...Nothing is known of the progress of this company, but it obviously had problems by the 1840s, since in a minute of the Sun Fire Office dated 9 December 1841 it is stated that the directors of the Glasgow office had agreed to pay the sum of £800 to relieve themselves of their liability.

A note appears at the foot of this minute to show that the amount of premium then in the hands of the Glasgow's agents was £950. The company then passed to the Sun Fire Office.

The Caledonian Insurance Company, Edinburgh 1805–1957

Emblem: A thistle, said to have been adopted as the Scottish national symbol after the battle of Laings, when a Danish invader trod on one, so giving away a surprise attack on the Scots, who then defeated the Danes.

Read more...The formation of a new Scottish company was initiated by one Forrest Alexander, whose property was severely damaged by fire and whose insurance claim for £600 was refused by the English insurers because the renewal of his premium had been delayed by one day owing to a communication difficulty. His company was to operate throughout Scotland and later other parts of the United Kingdom.

Along with Alexander, another director was the portrait painter Henry Raeburn, who designed the policy heading which continued in use until 1838.

The board of directors soon ordered a 'Tin Plate or Copper Ticket or office mark for affixing to insured buildings'. Within a few years it is recorded that almost half the houses in Prince's Street bore the Caledonian mark.

A fire brigade was formed with fourteen firemen who wore blue jackets with a thistle motif and trousers with orange inlays and turn-ups. The leather helmet bore a painted thistle with 'Caledonian' below it.

Some months after ordering fire marks, the company purchased an engine from Bramah & Son of London; this was stationed in the Wateryard, Castle Hill, and an alarm bell provided. The brigade was maintained by the Caledonian until 1824, when its engines were transferred to the Edinburgh Fire Engine Establishment. That same year the first manager of the Caledonian, William Braidwood, retired. It is not known whether he was related to James Braidwood, who commanded the Edinburgh Fire Engine

Establishment and was to command the London Fire Engine Establishment from 1833.

A Royal Charter was granted in 1810. The company did not venture into the overseas market until the 1870s. By 1813 agencies were set up in England and in 1834 a branch was opened in Dublin. Expansion continued, resulting in a removal of the head office to George Street in 1840, by which time the Caledonian was the oldest surviving Scottish insurance company. It continued to operate successfully and in 1957 became allied with the Guardian Assurance Company.

The Fife Fire Insurance Company 1806–1828

Emblem: Based on the arms of the Royal Burgh of Cupar. The three crowns of myrtle have been used by Cupar since at least the mid seventeenth century.

Read more...The company was established in March 1806 to transact fire insurance in and around Cupar, the county town of Fife. The board consisted of nine extraordinary directors led by the Earl of Kellie, with nine ordinary directors and a secretary. A number of agents were appointed at such places as Dunfermline, Dundee, Edinburgh, Glas-gow, Greenock and Perth.

Nothing is known about the business history of the company and the last entry concerning the Fife appears in the Fife and Kinross Register in 1828, and the company was presumably wound up in this year or shortly after.

The Hercules Fire Insurance Company, Edinburgh 1809–1849

No emblem was used on the fire mark, but the name Hercules is associated with a mythological figure symbolising strength.

By 1824 a fairly healthy fire account is suggested, by virtue of the price of a £10 share having almost doubled to £19.

Read more...In 1849 the Scottish Union acquired the fire business at a total cost of £4,368, which the proprietors decided to write off in ten years. At the time of the final take-over the premium income amounted to £8,000 per annum and the Hercules had ninety agents, all of whom were taken on by the Scottish Union.

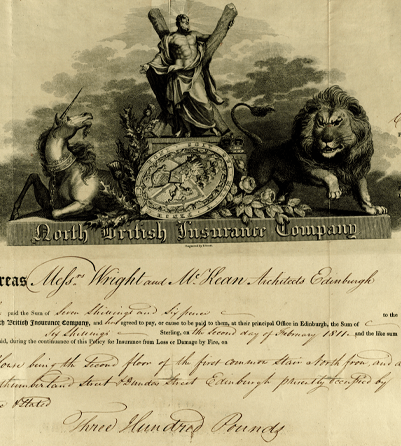

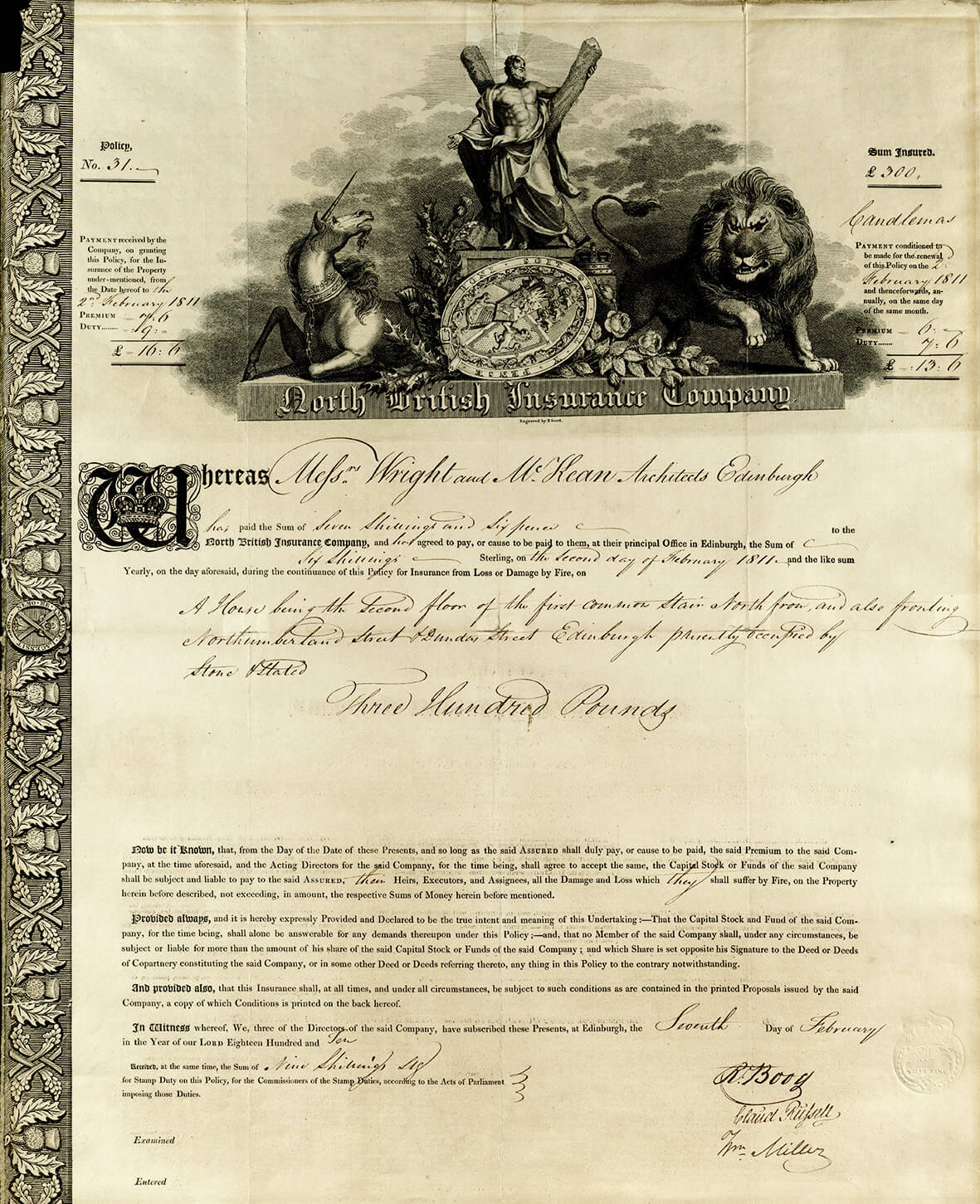

The North British Insurance Company, Edinburgh 1809–1862

Emblem: St Andrew, the patron saint of Scotland, who lived in the first century A.D. A fourth-century account records how he was crucified on a cross, which by medieval times was depicted as a saltire.

The Insurance Company of Scotland, Edinburgh 1821–1848

Emblem: The Scottish crown, made by order of James V of Scotland about 1540.

Formed in 1821, the company received a Royal Charter in 1839. The company was established with a capital of £76,000 in fully paid-up shares, all the shareholders being liable for any losses which the company was called upon to pay.

Read more...The fire portfolio passed to the Alliance, British and Foreign Fire and Life Insurance Company, after just twenty-six years in 1847. On 7 July 1847 the Alliance issued a directive that 'the use of the name and charter of the Scottish Company [is] to be continued as it related to fire business for the present as far as is legal and consistent, no greater change than is necessary be made in the ostensible management'.

The formal articles of agreement between the two companies were submitted and directed to be signed by the trustees on 9 February 1848.

The West of Scotland Insurance Company 1823–1838

Emblem: The larger mark depicts an English crown, represented heraldically and based on St Edward's Crown made for the coronation of Charles II in 1662. On the smaller mark is depicted the Scottish crown made by order of James V of Scotland about 1540.

Read more...The company, operating from a head office at 147 Buchanan Street, with the Duke of Buccleuch as chairman of the board, had by 1837 attained the sixth place in size of premium income among the eleven Scottish fire insurance companies operating at that time.

The company seems to have transacted foreign business from an early date, having been involved with a lawsuit in Upper Canada in 1825 and having an agency in Belfast.

Negotiations with the Phoenix to take over the business had begun in the preceding October, and on 2 January 1839 the board of directors of the Phoenix agreed to accept the business since its overseas connections seemed very attractive.

Irish insurance offices 1760 - 1823

Words courtesy of Brian Wright, images courtesy of the Chartered Insurance Institute

The Hibernian Insurance Company, Dublin 1771–1839

Fire mark, an Irish harp, a national symbol.

The first Irish company to transact fire insurance. The secretary was Christopher Deey, a public notary in Crampton Court, and the subscribed capital stock was £40,000, 25 per cent of which, subject to any losses, was invested in government debentures.

The Freeman's Journal of 21 May 1771 told its readers that: Persons of an affluent fortune, will surely think it prudent to guard against risks of this kind when they can cover a considerable amount of their property at such a trifling expense ... The importance of these observations is so well understood in England that the practise of insuring from losses by fire is almost universal in that Country. There, the credit of the trader would be injured if his house did not wear this mark of his attention to the security of his own and his Creditor's property, and it is much to be desired that the people of Ireland - particularly the trading part - should therein follow the example of that wise commercial Nation.'

At some date after 1788 the company began life assurance. In 1835 the Hibernian was the tenth-largest fire insurance company in Ireland. The half-year from Lady Day to Michaelmas 1838 produced an income of £491, slightly down on the previous year. However, losses amounted to £2,125 11s Id, of which one claim for a fire at a woollen mill came to £2,100.

The directors seem to have decided to discontinue business after the loss and so began negotiations with the Sun Fire Office to take over the fire business.

The General Insurance Company of Ireland, Dublin 1777–1825

Fire mark, a phoenix rising from the flames, used from the medieval period to symbolise resurrection.

Read more...The company was established by the Dublin bankers David La Touche and Joshua Pim and 140 other subscribers 'for the purpose of insuring Houses, Buildings, Furniture, Goods, Wares and Merchandise against Fire upon the most liberal and extensive plan, with a Capital Stock of £60,000'.

The premiums charged for common insurance in the first year of business ranged from 2s 6d per cent per annum for a sum insured of £500 to 5s per cent for a sum insured of £4,000 'and upwards by Special Agreement. Flour Mills also by Special Agreement.

The company uses the title of the General or Phenix Insurance Company Against Fire, and a few years later the title Phoenix Insurance Company of Ireland seems to have been adopted. In 1817 the same Almanack contains an advertisement, 'Mills with kilns, Steam Engines, Distilleries, Farming Stock and Factories insured at the most moderate rates'. Saunders' Newsletter of 16 June 1823 advertises that:

'This company although confined to insurance against Fire alone and not concerned with ship or Life Assurances can boast of an ample Capital Stock more than fully paid up, not depending on a trifling deposit of only 5 or 10 per cent on a Nominal Capital to make good the losses as some modern companies are, continue as usual to insure Dwelling houses and other Buildings, Wares and Merchandise against the Calamity of Fire on the same liberal and reasonable terms as heretofore.'

In Wilson's Dublin Directory for 1824 the company 'trust the experience of the Public has had on their punctuality in the immediate discharge of all demands on them since the year 1777 will be a sufficient inducement to give their office a preference', and in Martin's Commercial Guide published in 1825 the company 'propose as modern terms as any other company in Ireland' However, on the last page of Martin's Commercial Guide under the heading 'Additions and Alterations', the final sentence reads: 'The Phoenix Insurance Company of Ireland have given notice of discontinuence of the business of the company altogether.'

The Dublin Insurance Company 1782–1817

Emblem. Based on the arms of the City of Dublin.

The prime mover of this company was John Talbot Ashenhurst, who advertised in the Faulkiner Dublin Journal of 3 January 1782 for subscriptions for this new company from an address at 2 Exchange Alley, Dublin.

Read more...The company was established by eminent Bankers, Merchants and Traders and had fifteen directors and appointed agents in 'all the cities and principal country towns in Ireland'.

Ashenhurst continued as secretary of the Dublin until 1817 and in January of that year was advertising shares in the company for sale.

The company's fire engine was one of the first on the scene at the great fire at Mr Smith's home in Castle Street on 17 April 1817. The building was insured by the Royal Exchange Assurance, and the several company engines 'all united in their efforts which happily subdued the flames'.

In Saunders' Newsletter of 4 August 1817, Ashenhurst informed the Irish public that he had been appointed agent to the Phoenix Fire Assurance Company of London. In December 1817. 'John Talbot Ashenhurst ‘… is now ready to renew and issue New Policies without delay or trouble, and at the lowest rate... as agent to the London Phoenix Insurance Company ..’

The Royal Exchange Assurance Company of Ireland, Dublin 1784–1823

The City Hall of Dublin, which when the company was founded, was known as the Royal Exchange. The building is at Cork Hill, near Dame Stree.

Read more...Watson's Almanack for 1803 advertised that 'The business is conducted on the most liberal plan and on the same advantageoous terms as at The Royal Exchange and other insurance companies in London.'

The Sun Insurance Company of Dublin 1800–1804

Emblem: A sun, an easily recognised symbol, possibly copied from the emblem of the successful Sun Fire Office in London.

The company was established to transact insurance on lives and survivorships and to grant annuities which made provision for widows and children. The company transacted fire insurance as a separate department, but both operated from 35 Anglesea Street, Dublin.

Read more...In 1804 the company was amalgamated with the British Fire Office, and an advertisement states: