Ledger book from the de Rougemont Syndicate, Lloyd’s of London: Brazil and the River Plate

It is Archives’ Week in Brazil and the Insurance Museum were invited to participate at the invitation of Memoria MAG Seguros. We looked for an item in our small collection of archive material that relates to Brazil and found the de Rougemont ledger book, which records ships and cargo movements around the world during the year 1859. Within it are a few pages devoted to Brazil and the River Plate area.

Many items from companies’ pasts have been left, discarded and forgotten. Often a document which is no longer of use or has no purpose will be destroyed. Sometimes these items are simply put on a shelf, left in a cupboard and forgotten about. People move on, retire and new staff replace the old. If the books, office equipment and other paraphernalia survive a couple of generations, then someone may suddenly think “this is interesting, let’s not throw it away”. Usually, they get looked at, put back into the cupboard, and brought out every now and then as a “company curio”.

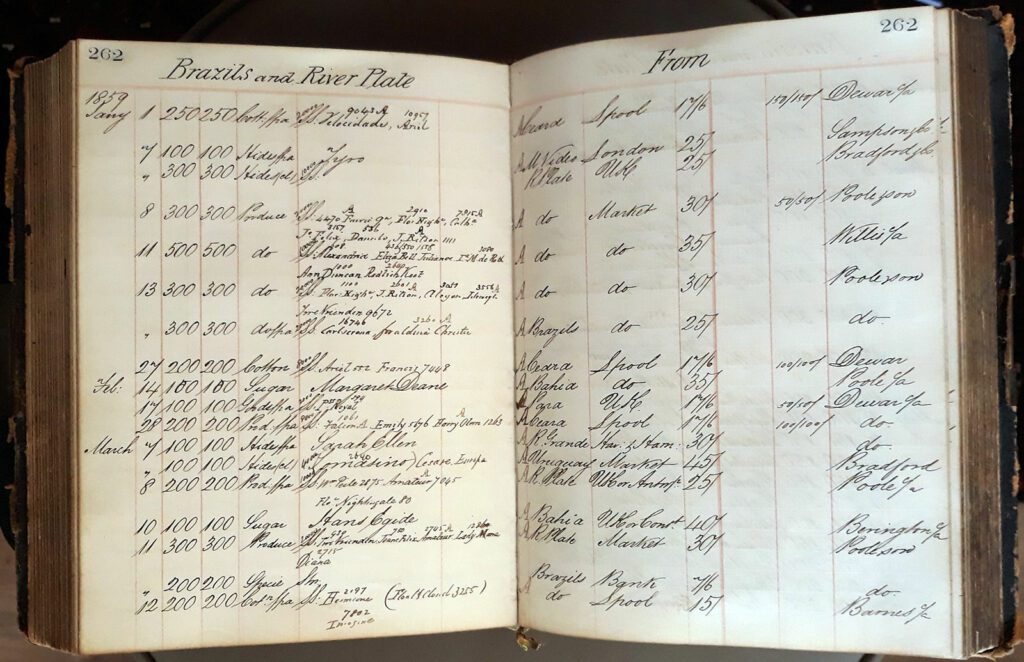

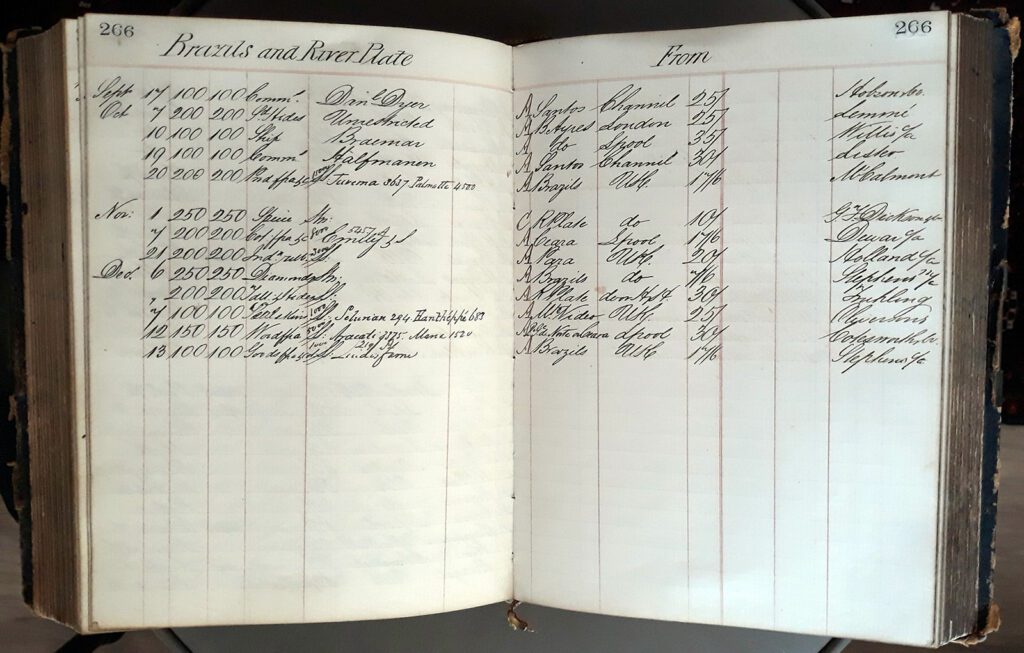

The de Rougemont ledger was one such item. It dates from 1859 and was found in a cupboard amongst 21st century office paraphernalia. It clearly shows shipping lists of that year in different parts of the world, and the risks underwritten.

Although there are no names associated with the business, we are fairly certain that it was from the de Rougemont Syndicate, a well-known name in the Lloyd’s market.

The business is ordered in categories based on geographical regions, for example, Hamburg and the North Sea, France and Holland, Sweden and Russia, Atlantic Ports, Africa, Mediterranean, and Brazil and River Plate. In fact, it covers almost the entire world.

There is information for each ship, with the date, the name of the ship, where it was travelling from, going to, and the cargo being carried.

The handwriting is pretty much consistent throughout the ledger, although it is in two hands, representing two people, who were probably the underwriters at the time, or their clerks. There is a third hand, making corrections, or updating the information. This handwriting is quite rushed, inconsistent, squashed into the space and looks very much like an afterthought.

Other than the facts, the underlying history that the book represents, is one of a worldwide trade in goods. Patterns can be picked up, with each geographical area trading in the particular goods it produces, such as:

- India – silk.

- The Baltic (lower ports) – wood, flax, wooden goods.

- The Caribbean and South America – sugar, coffee, cacao, cotton.

The specialisation of goods in geographical areas reflects deep historical, topographical and climatic characteristics. The Mediterranean is interesting, as it has always been the hub of worldwide trade and this is reflected in the variety of goods listed in the ledger: coffee, cigars and sulphates.

The Brazil and River Plate area covers the east coast of South America from Brazil to Argentina. The book refers to the cities and areas of Rio, Bahia, Ceará, River Plate, Buenos Aires and Montevideo amongst others. With a bit of work, you can track cargos and individual ships. In the 1850s, the main exports of Brazil were cacao, sugar, coffee, leather and skins (or hides), and rubber.

Here are a few examples:

- 27 January 1859, the ship Ariel, carried cotton from Ceará to Liverpool. On 11 March, Ariel sailed from Liverpool to Ceará carrying “Coals” and “Goods”. There are a few entries with the ship name Ariel, but this is probably the same one, as passage time across the Atlantic then was about 6 weeks, and the timings and ports match up. There are a few entries of cotton going from Ceará to Liverpool. Liverpool was well connected to the cotton mills of northern England, so it would be the natural port for cotton imports.

- 14 February, the Margaret Deane carried sugar from Bahia to Liverpool. Sugar was a popular commodity to export and there are several cargoes of sugar over the year.

- 1 March, the Sarah Ellen carried hides from Rio Grande. Hides are also a common export in the ledger.

- 8 to the 13 January lists a number of voyages with “Produce”. Sometimes the generic word “Goods” was also used. For each entry within these dates, the “Produce” was split over a number of ships. Could this be coffee? Coffee was one of the largest exports in the 1850s, and could well have been transported in mass quantities.

- 6 December has an unusual entry for this ledger. A ship carried diamonds from Brazil. Brazil had been the world’s greatest producer of diamonds. 1859 was still in this boom period, just before diamond mining took off in South Africa, which lead to a decline in the Brazilian diamond mining and trade.

The ledger is a snapshot of one year and one syndicate’s global maritime insurance business. Even so, it has a research appeal across the historical spectrum. Other than direct insurance and marine history, there is a wider story when it comes to social and economic world history. It has value for genealogists who can trace their ancestors to certain boats and, if the records allow, to certain voyages. The ledger can be linked to other collections, such as the Guildhall Library Maritime Collections. It will become part of the Insurance Museum’s collection and will contribute to the story of global insurance markets. Hopefully we will use it in our exhibitions and education programmes when the Insurance Museum secures a permanent venue in the City of London.