Beta Mode

Rising from the ashes

The birth of fire insurance

(1666-1696)

The Great Fire of London

2nd - 6th Sept. 1666

A massive fire swept through the City of London,

destroying everything in its path.

Eyewitness accounts provide a unique insight

into this catastrophic event.

Day two

Day three

Day four

Eyewitness accounts

To explore more first-hand eyewitness accounts from the Great Fire of London, you could look up the following people.

Samuel Pepys

English naval administrator Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) wrote an eyewitness account of the great fire in a diary he kept from 1659 to 1669. In it he states that he saw:

“The fire continuing, after dinner I took coach with my wife and sonn; went to the Bank side in Southwark, where we beheld that dismal spectacle, the whole citty in dreadful flames near ye water side; all the houses from the Bridge, all Thames Street, and upwards towards Cheapeside, downe to the Three Cranes, were now consum’d”.

John Evelyn

Another contemporary eyewitness was John Evelyn (1620 – 1706) who wrote of the fire:

“Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that lay off; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the water-side to another”

Why the fire spread so quickly

The fire started in Thomas Farriner's bakery in Pudding Lane.

Its rapid growth was caused by a number of factors.

It began at a bakers in Pudding Lane

Historians believe the fire probably started when a spark or ember from baker Thomas Farriner’s oven ignited something combustible, perhaps kindling wood or even flour dust from a busy day’s baking. By the time a maid had woken the Farriner household, the fire was already sweeping through the building.

The Farriners escaped by crawling from an upstairs window onto a neighbour’s roof, shouting ‘Fire, fire..,’ to raise the alarm. But the fire spread incredibly quickly and within minutes had reached adjoining buildings.

The maid who had alerted the Farriners to the fire, sadly was the first casualty of the fire, as she was too scared to jump from the burning building to the street below.

The spread of the fire from the bakery is vividly described by London Resident Edward Waterhouse, in the audio track below.

A floor plaque in Pudding Lane, where archeologists believe Thomas Farriner's bakery was located.

Buildings and contents

The speed with which the fire took hold was partly due to the fact that the City of London had many narrow streets filled with tall, narrow overhanging houses, all sitting dangerously close to each other.

In addition, many buildings in the area were poorly maintained, with exposed timber roof slats that would have been highly flammable.

At this time, properties were used for a mixture of activities. Many people would have lived above their place of work, as Thomas Farriner the baker did. They may have had a workshop, perhaps for weaving, upstairs and they stored a myriad of items for selling, use in their business or in return for some rental income.

Along with the merchant warehouses on the wharf, there was a multitude of combustible goods stored within the city.

These buildings that you can visit in the Shambles in York, demonstrate how buildings of the period were packed closely together. As the rooves are nearly touching, fire could easily jump from one building to another.

Environmental factors

It had been an unusually hot summer and the many buildings that were made of timber were all very dry and therefore combustible.

Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary, ‘So I at home all the evening doing business, and at night in the garden (it having been these three or four days mighty hot weather) singing in the evening, and then home to supper and to bed.‘

Another critical factor to the fire was a strong easterly wind that fanned the flames, driving the fire across the city. The strength of this wind was such that embers were blown as much as a mile away, igniting more and more fresh fires.

It was only when the wind stopped that it really became possible to extingush the fire.

Just another fire...

Had it been taken seriously, the fire had a chance of being contained at the start – had it been taken seriously. However, fire was a common occurrence at this time, so initially it was seen as ‘just another fire’.

Contemporary eyewitness Samuel Pepys seemed so unconcerned about it, he went straight back to bed after first hearing about it.

More concerning was the lack of action by the Lord Mayor of the time, Thomas Bloodworth. He was reluctant to create a fire break by pulling down large houses belonging to rich merchants. This may have been because he would have been responsible for the cost of replacing them afterwards. He is also reported to have dismissed the fire as not serious, saying that a woman could simply “piss it out”.

Fire was also often seen and accepted as the will of God’s and outside of their control.

Fire was a regular part of every day life , from cooking to heating and lighting, so accidents happened regularly.

Tour Guide

Learn more about the spread of the fire.

With Pete Zymanczyk

Filmed in front of the memorial to the Insurance Fire Brigades, at the London Fire Brigade in London.

(Excuse the noises-off from the fire station,)

How the fire was fought

At the time of the Great Fire, no fire brigades existed to slow the advance of the flames. Instead people fought fires with the help of their friends and neighbours. Even King Charles II and his brother the Duke of York, were directly involved in fighting the fire.

Parish churches were expected to store fire prevention tools such as those explored in this section.

Title #1 Title #1 Title #1

Title #2

Title #2

Collector

Engines and tools from the period of the Great Fire of London.

With Roy Rice, collector of manual fire engines (...and clocks)

Firefighting tools

Below are some of the tools used for firefighting

Bucket

Buckets were used as the main fire extinguisher at the time of the Great Fire. Friends and neighbours would form human chains passing buckets of water back and forth from the source of water to the fire.

Buckets were made from vegetable-tanned leather and were sealed with pitch, waxes and oils. They were leather stitched and had a leather clad rope handle.

(Image courtesy of R Long)

Squirt

Fire squirts were like giant water pistols. The squirt was used to suck up water (perhaps from a bucket) which could then be squirted at the fire. Some squirts needed two or three people to use them as they were quite heavy.

(Image courtesy of National Emergency Services Museum)

Hooks

A wrought iron fire hook like this one was used to pull flammable thatching from the roofs of buildings in an attempt to halt the spread of flames. It would have been attached to a wooden pole with a total length to about seven metres. Fire hooks were also used when pulling down houses to create fire breaks, to halt the spread of a fire.

One or two people and even a horse would be needed to help to pull some buildings down.

(Image courtesy of R Long)

Gun powder

Gun powder was sometimes used to blow up buildings to create fire breaks. The building that had been destroyed would be removed or soaked in water to stop or slow the progress of a fire.

Manual fire engines

Manual fire engines were in use at the start of the 17th century as a way of getting a force of water directed at the seat of the fire, but they weren’t terribly effective, as there wasn’t enough pressure to give them much power.

The engine consisted of a barrel of water with two pump arms either side, both ends worked by men, who would pump the arms to drive the piston, pushing water up like a giant syringe.

An early example of this type of engine were those produced by John Keeling.

Collector

Introducing a 17th-18th Century manual fire engine

With Roy Rice, collector of manual fire engines

'Douse the fire'

Kids, can you help put out the Great Fire of London?

Grab a bucket and help stop the fire

Play the game

(Opens in new window)

'London was, but is no more.'

John Evelyn recorded in his diary:

“ The poore inhabitants were dispers’d about St George’s Fields and Mooresfield’s as far as Highgate, and several miles in circle, some under tends, some under miserable hutts and hovells, many without a rag or any necessary utensils, bed or board, who from delicatenesse, riches and easy accommodations in stately and well-furnish’d houses, were now reduc’d to extremest misery and poverty. ”

Tour Guide

The City of London in ruins

With Pete Zymanczyk

Social impact

Before the fire, London had contained about a tenth of the population of England and half its wealth. As a result of the fire, over 100,000 people were left homeless, camping in makeshift tents in the fields surrounding the city and facing a winter without enough food and with totally inadequate shelter.

Many people had lost everything they had in the fire, including their livelihoods and business assets. Soon the debtor’s prisons of Ludgate, Fleet and Marshalsea were full of victims who suddenly found themselves in debt and many were never seen again.

Only six people were on record as having been killed by the fire, but an unknown number died in that first bleak winter following the disaster.

No-one was insured against the impact of the fire, so most were dependent on the charity of friends and the community. The Church of England raised charitable funds for recovery through a system of charitable drives, raising money for the victims of the fire.

With Fire Historian Brian Henham

Economic impact

With the destruction of homes, warehouses, machinery, public buildings and goods, the cost of rebuilding London was estimated at £10 million, at a time when London’s annual income was £12,000.

London had been England’s principal trading and manufacturing hub and its destruction diminished the government’s tax revenues. Aware of the necessity of supporting the city, King Charles II needed to take swift action.

As early as 13th September the King expressed the need to rebuild in brick or stone (as opposed to timber) and proposed street widening schemes. Although neither fully took off, The First Rebuilding Act laid down the standards for construction, receiving royal assent on 8 February 1667.

The government also faced the challenge of securing funds for the reconstruction of London. The Fire Court was set up to arbitrate disputes between landlords and tenants over the allocation of rebuilding costs. But it was the government’s responsibility to finance the reconstruction of public buildings. Much of this revenue was found through a new tax on coal entering London. By the early 1670s most of the public buildings in London had been rebuilt.

Surprisingly there was no initiative to create a fire brigade to protect the city against future fires.

With tour guide Pete Zymanczyk

Insurance Expert

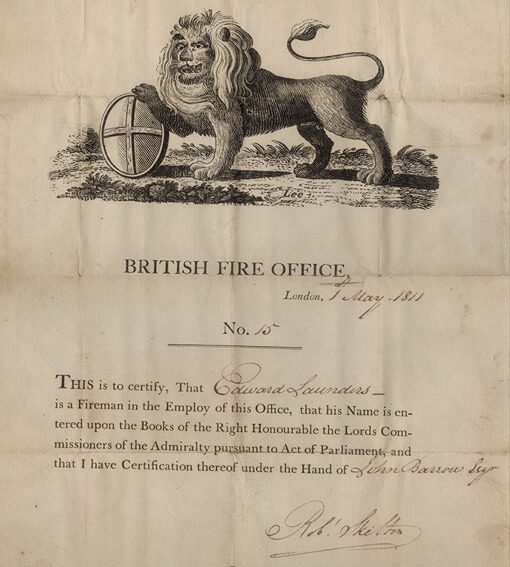

Schemes for those who suffered a fire loss

With Robin Pearson

Registered Charity address:

C/o Chartered Insurance Institute

3rd Floor, 20 Fenchurch Street,

London EC3M 3BY

Charity No. 1188138

Sign up to Newsletter

© Copyright Insurance Museum 2022

Registered Charity address:

C/o Chartered Insurance Institute

3rd Floor, 20 Fenchurch Street,

London EC3M 3BY

Charity No. 1188138

Sign up to Newsletter

© Copyright Insurance Museum 2026